National Provident Fund Commission of Inquiry Final Report (Serialization Parts 41-85)

Mentions of people and company names in this document

It is not suggested or implied that simply because a person, company or other entity is mentioned in the documents in the database that they have broken the law or otherwise acted improperly. Read our full disclaimer

Document content

-

National Provident Fund Final Report [Part 85]

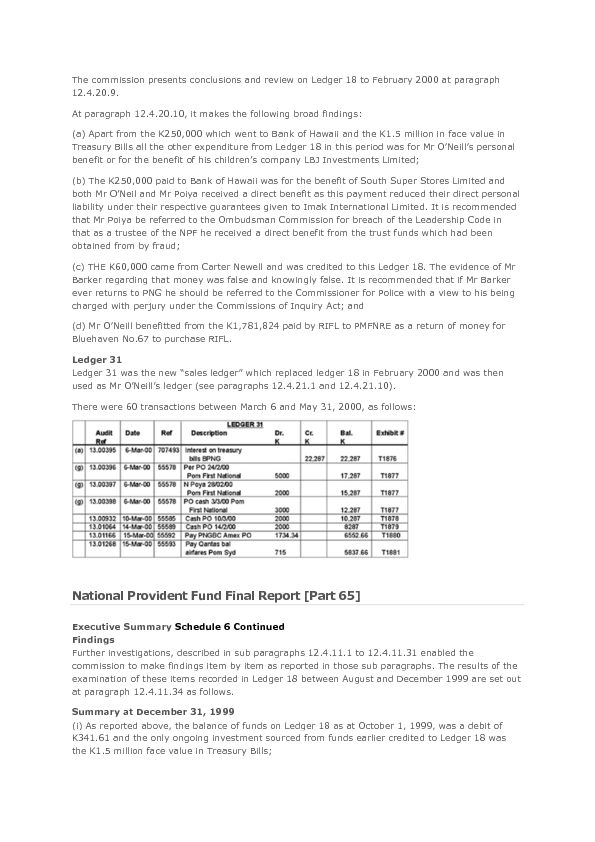

Executive Summary Schedule 9 Tender Procedures and Nepotism Continued Findings In paragraph 13.6.1.2, the commission has found that:

(a) The evidence before the commission clearly indicates that Mr Wanji’s conduct in his dealings with Laiks Printing, a company in which he was a shareholder, director and a cheque signatory, was improper. Mr Wanji stood to benefit from NPF, when he obtained quotes from Laiks Printing and recommended Laiks Printing to supply stationery and office supplies. This was not disclosed to the NPF by Mr Wanji;

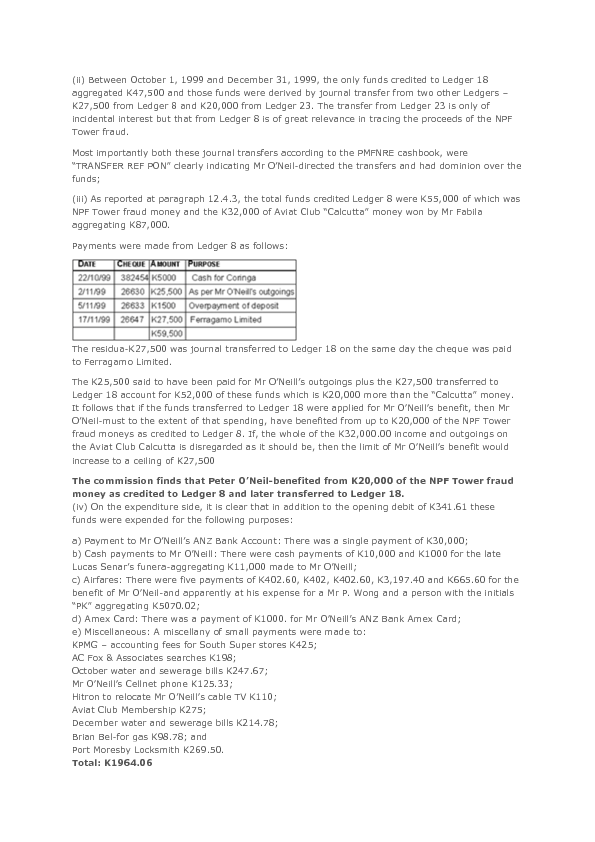

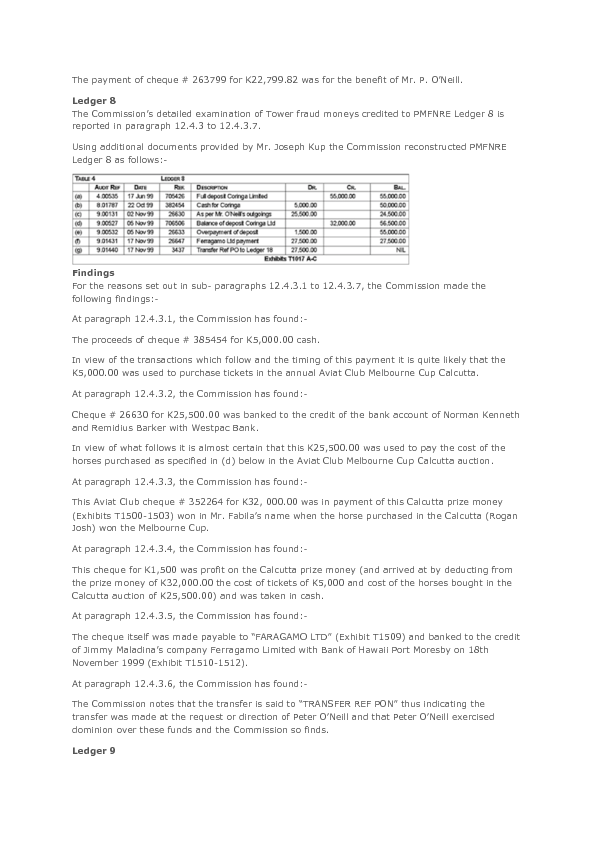

(b) It is likely that moneys were paid to Laiks Printing well in excess of the fair value of goods and services provided by them

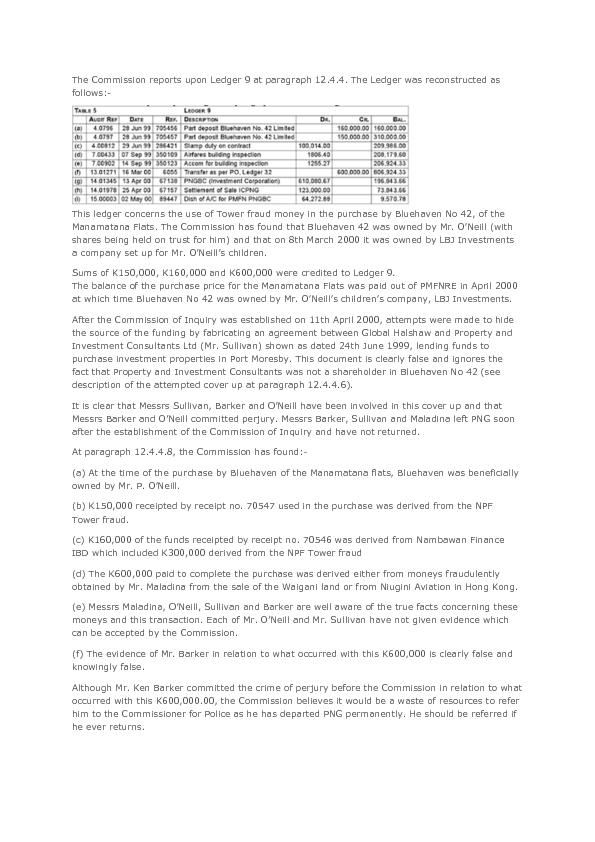

Warenam Office Supplies There were 12 purchases from this company to a value of K80,982.26.

Mr Alopea, the proprietor and manager of Warenam Office Supplies, voluntarily provided details of 16 secret payments to Mr Wanji totalling K12,530 during the period May 3, 1999 to June 14, 2000.

However, in actual fact, Mr Wanji received only K11,280.

Due to a loss of records at Warenam Office Supplies, other payments to Mr Wanji prior to May 3, 1999 could not be ascertained. Mr Wanji has admitted, in his evidence to this commission that these payments were made to him, personally, by Warenam Office Supplies, before May 3, 1999.

Findings At paragraph 13.6.1.5, the commission has found that:

(a) There was an agreement between Mr Wanji and Joe Alopea of Warenam Office Supplies that contracts would be awarded to Warenam in exchange for secret commissions paid by Warenam to Mr Wanji;

(b) On some occasions the secret commission was factored into the price paid by NPF;

(c) The relationship between Mr Alopea and Mr Wanji was criminal in nature. Mr Wanji received more than K11,280 from which he personally benefited. Mr Alopea and Mr Wanji should be referred to the Commissioner for Police for investigation.

Country-wide Business Supplies The commission has found that Mr Wanji received commission from Christopher Enara of Country- wide Business Supplies.

Other companies The commission inquired into Cando Investment and Stephens Enterprises. The investigations showed Mr Wanji received corrupt commissions from these companies.

Findings At paragraph 13.6.2.1, the commission found that:

(a) Given the weak internal control procedures, Mr Wanji used to decide, almost at will, how much to buy and from whom during the period covered. These weak controls resulted in Mr Wanji obtaining benefits from suppliers including the purchase of stationery and office supplies from his company, Laiks Printing;

(b) The benefits Mr Wanji received from the suppliers were in fact “bribes” or “commissions” and not loans;

-

Page 2 of 190

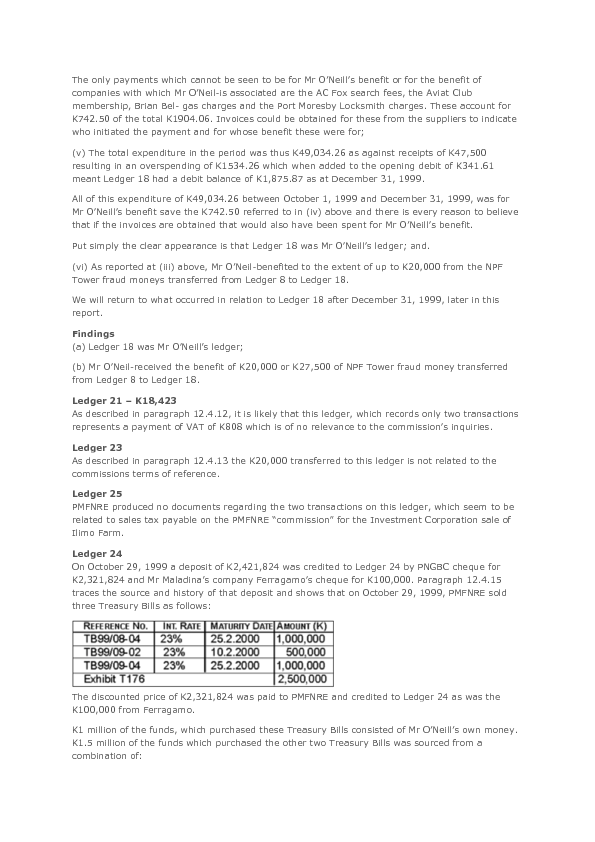

-

(c) The commission considers that there is sufficient evidence of criminal offences of the nature of conspiracy to defraud. The commission recommends that Mr Wanji be referred to the Commissioner for Police for further investigation.

Funds obtained from NPF housing advances scheme Cando Investments Mr Wanji applied for and received K2200 from the NPF Housing Advance Scheme for repair and maintenance work to his house, to be carried out by Cando Investment, which had quoted for the work. However, this money was not used for the said work on the house.

Mr Wanji claimed he engaged another contractor to do the quote, which was completely different from the quote used to obtain the money.

He then requested and benefited from the refund from Cando Investments.

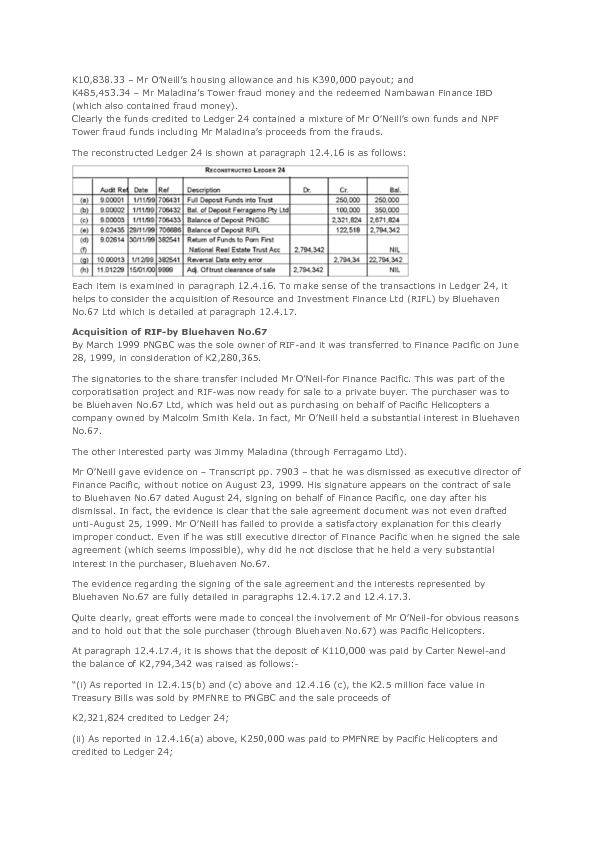

Findings At paragraph 13.8.2.1, this commission has found that:

Simon Wanji dishonestly obtained the payment of K2200 from Cando Investments for his own benefit. The money had been provided by NPF to Cando Investment for a different purpose.

A similar situation occurred with two other NPF officers, Max Noah and Kanora Aua, who requested money from the Housing Advances Scheme and used the money for other purposes than they stated in the request form.

Findings At paragraph 13.8.5, this commission has found that:

(a) NPF advanced the funds for specific work to be carried out by Cando Investments. However, Mr Wanji, Mr Noah and Mr Ava obtained the funds from Cando Investments and either used the funds for a different purpose or arranged for the work to be carried out by a different contractor or both, which was contrary to the purpose for which NPF advanced these funds;

(b) Cando Investments appears to have been a facilitator of these arrangements, taking a 10 per cent commission. The funds should have been reimbursed to NPF but Cando Investments failed to do this and in repaying funds to the NPF member, enabled that person access to his funds not available to other members;

(c) The payments from NPF to Cando Investments may have been made on false representation. Cando Investments may have facilitated obtaining from NPF under this false representation and later paid those funds (less commission) to the NPF member;

(d) The commission considers that there is sufficient evidence of criminal conduct and recommends referral of the following persons to the Commissioner for Police for further investigation as to whether the offence of obtaining money by false pretence or by fraud or conspiracy to defraud has been committed. Simon Wanji, Max Noah, Kanaro Ava and Pere Enara of Cando Investments;

(e) The following matters should also be referred to the Police for investigation:

• Suspicious payments made by suppliers to Mr Wanji; • Mr Wanji’s dealings with Laiks Printing and Bubia; and • Mr Koae’s dealings with Bubia. Concluding Comments At paragraph 14, the commission concludes::

The commission’s investigations have shown that at the beginning of the period under review, there was some attention given to calling for tenders and seeking competitive quotations for procurement of some of the goods and services examined in this report.

-

Page 3 of 190

-

As time went on, these frail attempts to comply with proper procedures lapsed and management increasingly ignored the concept of obtaining competitive quotations.

Management also ignored the need to keep the NPF board informed or seek its approval.

This gross laxity allowed the development of nepotism and criminal acts to defraud the NPF.

It is a very sad story for which NPF senior management is primarily to blame. The NPF trustees, however, had a fiduciary duty to ensure the fund was well managed and its finances were protected.

They failed this duty totally. The abuses were so noticeable that the trustees’ failure to notice and address it, constitutes a breach of their fiduciary duty to the members of the fund and may constitute a breach of the Leadership Code by all trustees who held office during the period under review. This matter should be referred for consideration by the Ombudsman.

Schedule 10 Exemptions: On June 29, 1981, a general exemption was granted to all organisations which were engaged in:

(i) Agriculture industry organisations involved in production of crops or livestock;

(ii) Agriculture processing organisations (including veneer and plywood industries) who are involved in the first stage of processing of agriculture and livestock products, but excludes industries involved in the production and/or processing of fish and other forest products.

This exemption was continued by a series of extensions. On September 30, 1993, Sir Julius Chan exempted all coffee growing and processing establishments “until further notice”.

These general exemptions and extensions for these classes of establishments ignored the very different types of employees in the industries, which ranged from low paid casual rural workers to skilled managers and accountants. Under the exemptions all employees were precluded from joining and contributing to NPF.

Coffee Industry Corporation (CIC) proposes a superannuation scheme This differentiation in types of employees was highlighted when CIC endeavoured to set up its own superannuation scheme for its skilled employees in January 1996.

The NPF board directed management to recommend that the Minister should lift the exemption in relation to the coffee industry so that appropriate employees could join NPF and so employer contributions could be enforced, but enforced fairly “noting the seasonal nature of the industry”.

Exemption lifted throughout coffee industry Minister Haiveta lifted the exemption as it applied to all establishments in the coffee industry, without regard to the different classes of employees, leaving NPF to sort out with individual employers which employees would be covered.

This ad hoc decision-making was unsatisfactory and did not address the same problem, which applied to other exempted agricultural industries.

Findings At paragraph 9.1.2, the commission found that:

(a) Because of the predominance of low paid seasonal rural workers and the low product prices, it was decided to grant relief to this sector by way of a general exemption to those organisations in the agriculture industry and processing. However, there were other employees who were employed by these agriculture establishments who were located and employed in urban areas and were receiving higher urban wages. When granting the exemption to the agriculture sector in 1993, this difference should have been taken into consideration so that those higher paid employees in urban areas are given the opportunity to contribute to the fund;

-

Page 4 of 190

-

(b) When the exemption applying to the coffee industry was lifted in May 1996, the difference between permanent, urban, casual and rural employees was again not sufficiently addressed and the lifting of the exemption simply applied across the board to all establishments in the coffee sector. This led to ad hoc decision making and confusion in the application of the Act.

Specific Exemptions Already Granted According to documents obtained from the Office of Legislative Counsel, the following establishments have been exempted by the managing director under Section 42 of the Act, as they had superannuation schemes at least as favourable as the NPF scheme and the Minister was satisfied the employees wished the exemption to be granted: Bougainville Copper Ltd exempted in 1984 and again in 1986.

Ok Tedi Mining Ltd was exempted in May 1991. From February 1994 until late 1997, the NPF board and management made half-hearted attempts to encourage the unions to lead the OTML employees into the NPF, as OTML management had expressed its willingness. It seems Mr Leahy, Mr Paska and Mr Leonard failed to follow through on this matter. Despite being exempted under Section 42 of the Act, OTML remained liable to report on its superannuation scheme as directed pursuant to Section 43. This was not followed up by NPF.

Findings At paragraph 10.2.1, the commission found:

(a) The statutory instrument does not expressly exempt OTML from Section 43 of the Act; Management failed to advise OTML of this factor during their discussions;

(b) Trustee Leonard failed in his fiduciary duty to the board and NPF by not completing the task given to him by the board through a proper board resolution and his failure to advise the board on the progress or otherwise, about OTML staff move to join NPF.

(c) All trustees and NPF management failed in their duty to proactively pursue the possibility of engaging OTML employees in the NPF scheme.

(d) The exempted establishments remained bound by Section 43 to report to NPF as directed. NPF failed to follow through on this aspect.

National Provident Fund Final Report [Part 84]

Executive Summary Schedule 9 Continued Tender Procedures and Nepotism Management contract price in excess of NPF Board approval The total cost of the new AS400 machine was within the amount approved under Section 61 of the PF(M) Act. However, the amount paid was greater than the earlier quotes provided by Datec to NPF and on which the board provided its original approval.

Evidence given by Mr Ta’eed and Mr Vere of Datec Mr Ta’eed gave evidence (Transcript pp. 8128-42) that:

• The AS400 which NPF had was over utilised; • Datec had advised NPF that a performance analysis of the computer system was required; • The return advice revealed that the system was too small for NPF’s needs, which was already known. Reasons for choosing the AS400 Mr Ta’eed advised that:

• The software NPF required ran only on AS400 machines;

-

Page 5 of 190

-

• A different machine with a different software had to have everything converted to the AS400, which is exactly what happened in 1993 when NPF moved from the McIntosh system to AS400. • NPF was the only authorised reseller of IBM equipment in PNG and the only service centre in PNG. Findings At paragraph 12.5.7.5, the commission found that:

(a) Once NPF had committed itself to Datec and purchased both software and sophisticated unique hardware it, was hooked into Datec/IBM with Datec being the only supplier in PNG. There was then no scope for seeking competitive tenders; and

(b) NPF management and trustees failed their duty to NPF members in not seeking independent expert opinion and advice before making this commitment to Datec.

1999 There were imperfections in NPF accounting records for the financial years 1998 and 1999 as mentioned in paragraph 12.6.

Computer purchase in 1999 See previous table Disposal of computer equipment in 1999 The fixed asset register did not record any disposal of computer equipment in 1999. However, old Y2K non-compliant computers were disposed of by tender, restricted only to NPF staff. This method of disposal of assets can be criticised as a form of nepotism. Clearly, NPF did not determine the market values of these computers and therefore would have lost substantial income for its members.

Findings At paragraph 12.7, the commission has found that:

(a) NPF management were in breach of Section 61 of the PF(M) Act by not seeking board and Ministerial approval for the additional expenditure incurred in the purchase of the new computer hardware;

(b) Management failed in their fiduciary duties for not seeking the maximum price for the used PC’s and other computer equipment sold during this period;

(c) THE Board and Management failed in their fiduciary duties to seek a second opinion about the new computer hardware they were purchasing;

(d) The sale by tender of PC’s and other computer related hardware to staff, without obtaining a proper market value for them, is deemed an act of favouritism and nepotism and loss of additional income to members of the fund; and

(e) Mr Wright exceeded his financial delegation in approving a Bloomberg Screen for his own office use, costing K41,515.03. He is personally liable for the loss suffered by NPF because of this purchase.

Procurement Of Stationery And Office Supplies NPF’s financial statements for 1995 to 2000, recorded various costs for stationery and office supplies.

Costs were constant from 1995 to 1998 but took a quantum leap in 1999.

While the commission understands that some increases can be attributed to the general increase in cost in the country due to economic factors in 1999, the increased cost in stationery and office supplies cannot be fully explained by such economic factors.

This view is clearly supported by the fact that stationery and office supplies cost for 2000, returned to its normal level.

-

Page 6 of 190

-

The main report (Schedule 9), seeks, in particular, to identify whether:

• There was failure to comply with tender procedures; • Such failures benefited any person; • There was any conflict of interest in the procurement of these services. • There was any conflict of interest in the procurement of these services. Summary of suppliers used between January 1, 1995 and December 31, 1999 Out of the total 10 suppliers listed, only four are commonly recognised suppliers. There was also an increase in the amount of purchases from unrecognised suppliers.

The Finance Department inspectors report also uncovered numerous procedural irregularities and weaknesses in this area. The same was found by the Auditor-General in his audit of financial statements for the years ended December 31, 1998 and 1999.

The state of control over procurement, recording and payments — 1995 to 1999 Procurement: Simon Wanji was responsible for ordering stationery and office supplies. There was no management control over what Mr Wanji was doing.

The only control at the time was that each order had to be accompanied by three written quotes.

Recording Creditors Normally in many companies, the monies for goods received would be recorded in the creditors ledger and paid after 30 days.

The NPF accounting package used in the period 1995 to 1999 did not have an auditor’s subsidiary ledger. Creditors were only recommended at year-end for reporting purposes, based on unmatched work orders, purchase orders and claim forms.

Payment of creditors Payment of creditors was ad hoc. NPF did not operate a scheduled payment policy.

Review of payments made Documentation of the procedures in place between 1995 and 1999 in respect of procurement, recording and payment, reveals crucial weaknesses and in particular, the lack of segregation between ordering and receiving goods, and recording liability and payment to suppliers. Given this situation, there was a high risk of nepotism, fraud, theft and errors occurring and remaining undetected.

Weaknesses identified • There was a complete lack of segregation of duties, and functions between ordering, receiving, recording and payment for goods which were, in almost all instances, performed by one officer, Mr W anji; • The minimum number of three written quotes were not always obtained; • Payment requisitions did not always indicate that the cheque raised was for goods and services; and • A creditors subsidiary ledger was not maintained. Benefit derived Evidence before this commission indicated that Mr Wanji derived substantial benefits while in his position as officer in charge of accounts payable.

It is also evident that Siri Koae, through his wife, might have also derived benefits but it was to a much lesser degree.

Findings At paragraph 13.5.5, the commission has found that:

-

Page 7 of 190

-

(a) There were inadequate procedures in place regarding the procurement, recording and payment of stationery and office supplies. These weaknesses are a significant break down in the control and safeguard of NPF finances;

(b) The controls, which were in place for the procurement, recording and payment of stationery and office supplies, were weak and therefore provided the conditions for nepotism and employee fraud to occur and remain undetected;

(c) Management failed to address procedures for a long time. Through the review of the payment vouchers the commission has come across written notes by Ms Dopeke and once by Henry Fabila, notifying Mr Wanji to obtain three quotes and queries as to why so much stationery was being purchased. These comments were ignored;

(d) These weaknesses resulted in nepotism, “bribes” and other benefits to staff at the expense of NPF;

(e) Mr Wright and Ms Dopeke failed in their duties to the board to identify weaknesses and install appropriate controls and procedures in the financial management of the fund.

Siri Koae Mr Koae was the manager of the NPF Lae branch between October 1993 and January 1999.

Mr Koae gave stationery and office supplies orders to Bubia, a firm of which his wife, Ms Lari, was co- owner. Ms Lari was also a director of Laiks Printing, a company that provided stationery and office supplies to NPF.

Mr Koae maintained that he received no benefits from Bubia or Laiks Printing.

Findings At paragraph 13.7.4, the commission has found that:

While the evidence does not disclose any criminal act by Mr Koae, his actions were in the commission’s view, improper and dishonest in that he disclosed quotes of other competitors to Bubia and failed to disclose his clear conflict of interest to NPF management.

There is a clear case of nepotism.

Examination of benefits received by Mr Wanji Laiks Printing Mr Wanji was a director of Laiks Printing as well as a cheque signatory on its cheque account.

Ten of 15 quotes from Laiks Printing were obtained verbally by Mr Wanji and he recommended that NPF purchase from Laiks Printing.

National Provident Fund Final Report [Part 83]

Executive Summary Schedule 9 Continued Ken Yapane & Associates Ken Yapane & Associates were employed to refurbish an office on the ground floor of NPF’s Head Office. This work was not tendered and Ken Yapane was paid an exorbitant K40,000 contract sum in advance without any work being done on the office refurbishment. He paid half this amount back to Mr Maladina. This same Ken Yapane was also involved in the NPF Tower fraud when Mr Maladina utilised Mr Yapane as a notional contractor and laundered money through his bank account to transfer money from Kumagai Gumi to Carter Newell’s office. Mr Maladina paid Mr Yapane a generous commission for his service. The similarities between Mr Yapane’s role in the Tower fraud and this office refurbishment contract are compelling. In both

-

Page 8 of 190

-

cases, the payment from Mr Yapane to Mr Maladina was laundered through the Carter Newell John Losuia account then paid to Mr Maladinas company, Kuntila No. 35 Pty Ltd. The commission has found that the advance payment to Mr Yapane of K40,000 for work he did not do was improper, that Mr Leahy was knowingly involved and that the ultimate beneficiary was Mr Maladina. Findings At paragraphs 9.3.5 and 9.6.1, the commission has found that: (a) The advance payment to Mr Yapane & Associates was improper. Management, and more specifically, Mr Leahy should be held responsible as he was the one responsible for authorising this payment; (b) Mr Leahy was responsible for fabricating the minutes of a fictitious NPF board resolution increasing his financial delegation to K50,000 in order to enable him to authorise the payment of K40,000 to Mr Yapane; (c) Mr Leahy should be held accountable for improperly paying K40,000 to Mr Yapane because no work had been or was done; (d) Management failed in their fiduciary duties to properly tender this job and obtain board approval for this expenditure; (e) The fact that Mr Maladina demanded and received at least K20,000 of the fees paid to Mr Yapane is grossly improper; (f) The evidence of criminal interest and association coupled with the evidence of similar conduct in the NPF Tower fraud involving the same persons strongly suggests that there was a criminal conspiracy to cheat and defraud the NPF involving Mr Maladina, Mr Leahy and Mr Yapane which was successfully implemented; and (g) MR Maladina, Mr Leahy and Mr Yapane should be referred to the Commissioner of Police to consider whether criminal charges should be laid against them. NEC Secretariat In September 1996, Hon. Chris Haiveta wrote to Mr Kaul and requested a donation towards the payment of sing-sing groups that were to perform at an NEC meeting in Vanimo. Mr Haiveta has given evidence (Transcript p. 8477) that he asked NPF management if they could help.

He was not told that NPF was not able to help. He said (Transcript p. 8479) that at the time he requested NPF to help, NPF had previously given donations and sponsored other activities like golfing days. Mr Kaul responded positively to this request. Findings At paragraph 9.7.1, the commission has found that: (a) MR Haiveta’s request for K1600 was improper and he should be referred to the Ombudsman Commission to consider taking action for a breach of the Leadership Code; (b) THE decision by Mr Kaul and Mr Wright to agree to the payment was a breach of their duty to the members of the fund and amounted also to improper conduct; (c) AS Mr Kaul was subject to the Leadership Code, he also should be referred to the Ombudsman Commission. Disposal Of Assets During the period covered by this enquiry, NPF disposed of some office furniture and equipment through tenders restricted to NPF staff members and by “in-house” raffles to fund Christmas parties and the like. This action by management deprived members of the fund from realising maximum financial benefits from the sale of these assets. Findings In paragraph 10.3, the commission has found that: The sale of NPF assets, such as the Kwila table and television and video deck, to staff without determining a reserve price for the items and without open tender, can lead to accusations of

-

Page 9 of 190

-

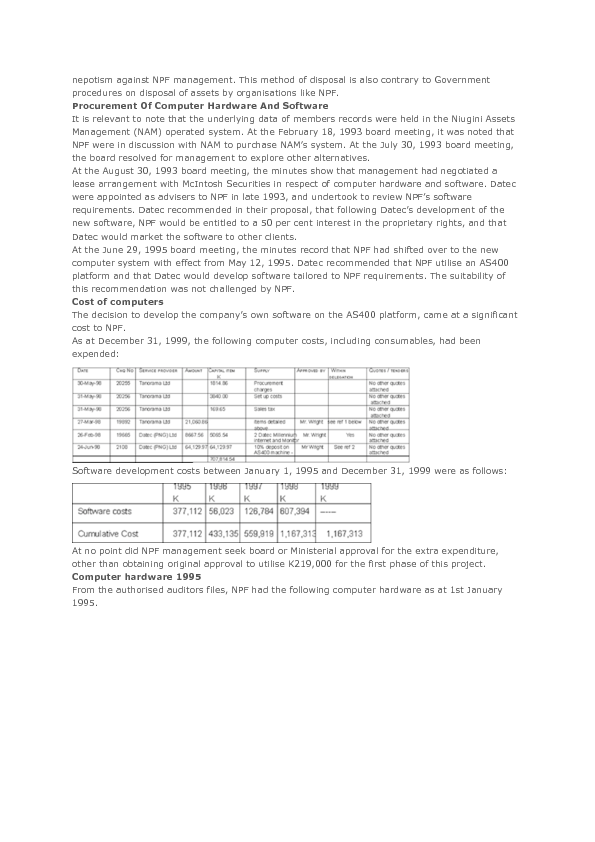

nepotism against NPF management. This method of disposal is also contrary to Government procedures on disposal of assets by organisations like NPF. Procurement Of Computer Hardware And Software It is relevant to note that the underlying data of members records were held in the Niugini Assets Management (NAM) operated system. At the February 18, 1993 board meeting, it was noted that NPF were in discussion with NAM to purchase NAM’s system. At the July 30, 1993 board meeting, the board resolved for management to explore other alternatives. At the August 30, 1993 board meeting, the minutes show that management had negotiated a lease arrangement with McIntosh Securities in respect of computer hardware and software. Datec were appointed as advisers to NPF in late 1993, and undertook to review NPF’s software requirements. Datec recommended in their proposal, that following Datec’s development of the new software, NPF would be entitled to a 50 per cent interest in the proprietary rights, and that Datec would market the software to other clients. At the June 29, 1995 board meeting, the minutes record that NPF had shifted over to the new computer system with effect from May 12, 1995. Datec recommended that NPF utilise an AS400 platform and that Datec would develop software tailored to NPF requirements. The suitability of this recommendation was not challenged by NPF. Cost of computers The decision to develop the company’s own software on the AS400 platform, came at a significant cost to NPF. As at December 31, 1999, the following computer costs, including consumables, had been expended:

Software development costs between January 1, 1995 and December 31, 1999 were as follows:

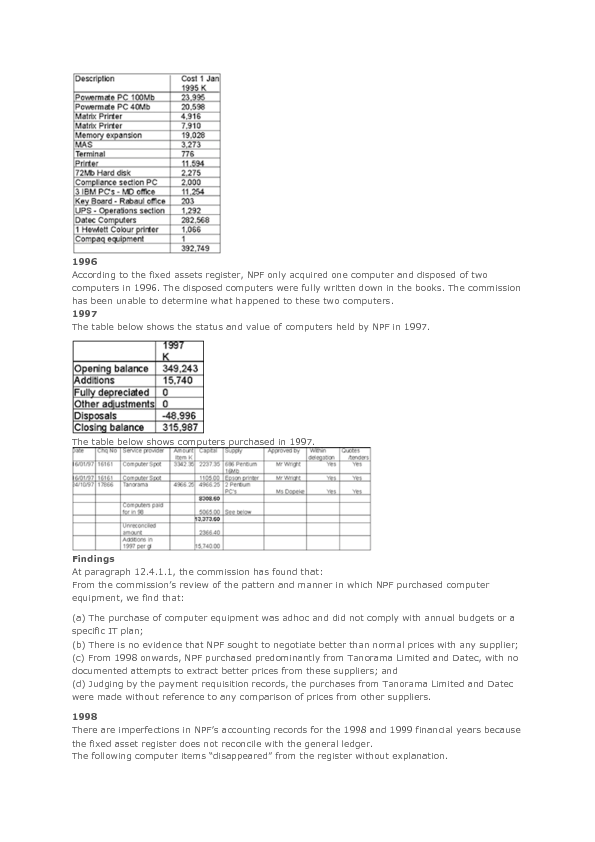

At no point did NPF management seek board or Ministerial approval for the extra expenditure, other than obtaining original approval to utilise K219,000 for the first phase of this project. Computer hardware 1995 From the authorised auditors files, NPF had the following computer hardware as at 1st January 1995.

-

Page 10 of 190

-

1996 According to the fixed assets register, NPF only acquired one computer and disposed of two computers in 1996. The disposed computers were fully written down in the books. The commission has been unable to determine what happened to these two computers. 1997 The table below shows the status and value of computers held by NPF in 1997.

The table below shows computers purchased in 1997.

Findings At paragraph 12.4.1.1, the commission has found that: From the commission’s review of the pattern and manner in which NPF purchased computer equipment, we find that:

(a) The purchase of computer equipment was adhoc and did not comply with annual budgets or a specific IT plan; (b) There is no evidence that NPF sought to negotiate better than normal prices with any supplier; (c) From 1998 onwards, NPF purchased predominantly from Tanorama Limited and Datec, with no documented attempts to extract better prices from these suppliers; and (d) Judging by the payment requisition records, the purchases from Tanorama Limited and Datec were made without reference to any comparison of prices from other suppliers.

1998 There are imperfections in NPF’s accounting records for the 1998 and 1999 financial years because the fixed asset register does not reconcile with the general ledger. The following computer items “disappeared” from the register without explanation.

-

Page 11 of 190

-

• 1 Compliance Section PC; • 3 IBM PC’s from MD’s office; and • 1 UPS from operation. With regard to the acquisition of other computers in 1997, NPF management obtained quotes from various suppliers before making a commitment to purchase the equipment. There is no documentary evidence found by the commission that would suggest that NPF management or the trustees sought to establish a documented and formal purchase policy in respect of computer equipment. The purchase of computer equipment, particularly at NPF where IT is a critical function, required careful scrutiny by management and the trustees, both in terms of enforcing an appropriate and proper functioning system, but also because of the high level of cost involved. Computers purchased in 1998 Chq No 20953, 15-Sep, Datec (PNG) Ltd, K587,837.07(amount), K587,837.07 (capital), AS400 hardware, 9406-620-2175, approved by board, See ref 2, no other quotes attached; Chq No 0952, 15-Sep, Tanorama Ltd K9301.67 (amount), K4789.50 (capital), two P166 multimedia packs for Ms Dopeke / J Sema, approved by Ms Dopeke, within delegation, no other quotes; Chq No 20952, 15-Sep, Tanorama Ltd, K2220 (capital), one P166 mmx 15” monitor, approved by Ms Dopeke, within delegation and no other quotes; Chq No 20952, 15-Sep, Tanorama Ltd, K695 9capital), HP Scan jet Desktop scanner, approved by Ms Dopeke, within delegation, no other quotes; Chq No 20952, 15-Sep, Tanorama Ltd, K955.75, procurement plus set up, approved by Ms Dopeke, within delegation, no other quotes; Chq No 20252, 27-May, Tanorama Ltd K21,060.86 (amount), 26,450.40 (capital), 12 P166MMX 16Mb RAM 2.5gb, 15”, approved by Mr Wright, see ref 1 below, no other quotes; Chq No 20253, 28-May, Tanorama Ltd, K9146.40 (capital), four P166MMX 32Mb RAM 2.5gb, 15, no other quotes; Chq No 20254, 29-May, Tanorama Ltd, K700.40 (capital), software, no other quotes; Chq No 20255, 30-May-98, Tanorama Ltd, K1814.86 (capital), procurement charges, no other quotes; Cheq No 20256, 31-May-98, Tanorama Ltd, K3840 (capital), set up costs, no other quotes; Chq No 20256, 31-May-98, Tanorama Ltd, K169.65 (capital), sales tax, no other quote; Chq No 19892, 27-Mar-98, Tanorama Ltd, 21,060.86 (amount), items detailed above, approved by Mr Wright, see ref 1 below, no other quotes Chq No 19665, 26-Feb-98, Datec (PNG) Ltd K8667.56 (amount), K5065.54 (capital), two Datec Millennium internet and monitor, approved by Mr Wright, within delegation, no other quotes; Chq No 2108, 24-Jun-98, Datec (PNG) Ltd, K64,129.97 (amount), K64,129.97 (capital), 10 per cent deposit on AS400 machine, approved by Mr Wright, see ref 2, no other quotes. Total: K707,814.54 Purchase of AS400 machine The purchase of the new AS400 computer hardware seems to have resulted from concerns about the “Year 2000 Bug” and the capacity and efficiency of NPF’s current computer system to cope beyond the year 2000. Failure to seek analysis by an Independent expert Quite glaringly, NPF did not seek independent advice about the AS400 machine. However, it is apparent that NPF relied on Datec’s recommendation. There is no evidence that NPF sought a second opinion on its proposal to purchase this AS400 machine from an independent computer consultant.

-

Page 12 of 190

-

National Provident Fund Final Report [Part 82]

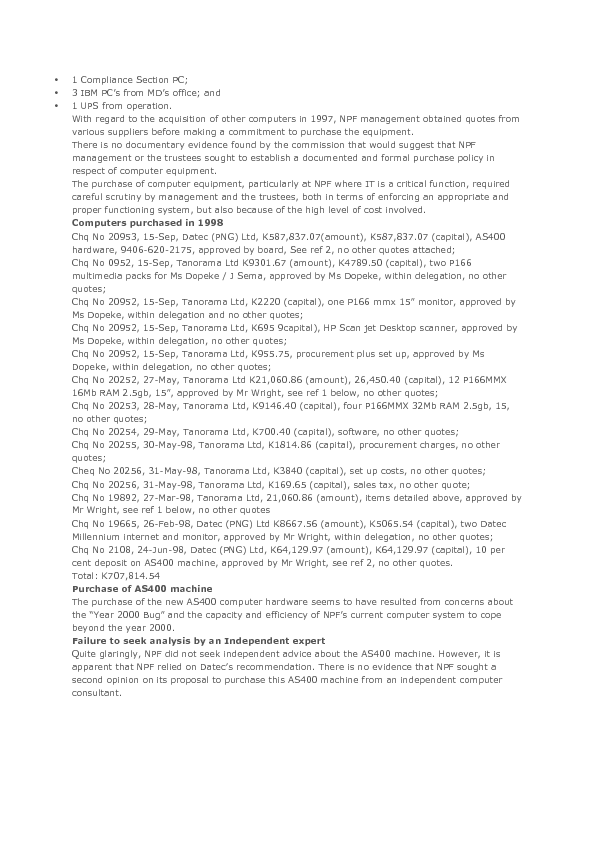

Executive Summary Schedule 9 Continued Fees Paid to accountants in 1996 1997 and 1998

The situation in 1998 remained basically the same as the previous three years. However, as far as outsourcing of accounting work was concerned, a significant part of the costs at the end of 1998 was charged to 1999 accounting cost.

When Noel Wright (a qualified chartered accountant) left in January 1999, the responsibility for the accounting positionmoved to Salome Dopeke.

-

Page 13 of 190

-

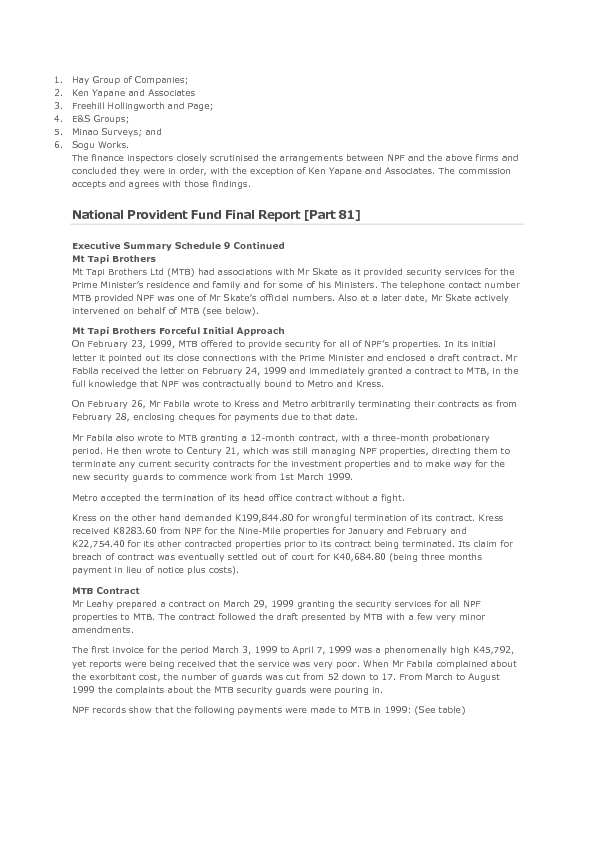

The commission finds that Ms Dopeke was not suitably qualified and experienced and lacked appropriate skills to take on this role. A draft section 8 letter prepared by the authorised auditors for the year ended December 31, 1998, included items that deal with weaknesses in the accounting area and requested NPF to address these weaknesses.

NPF therefore sought out accounting firms to assist them in having their accounts brought up to date.

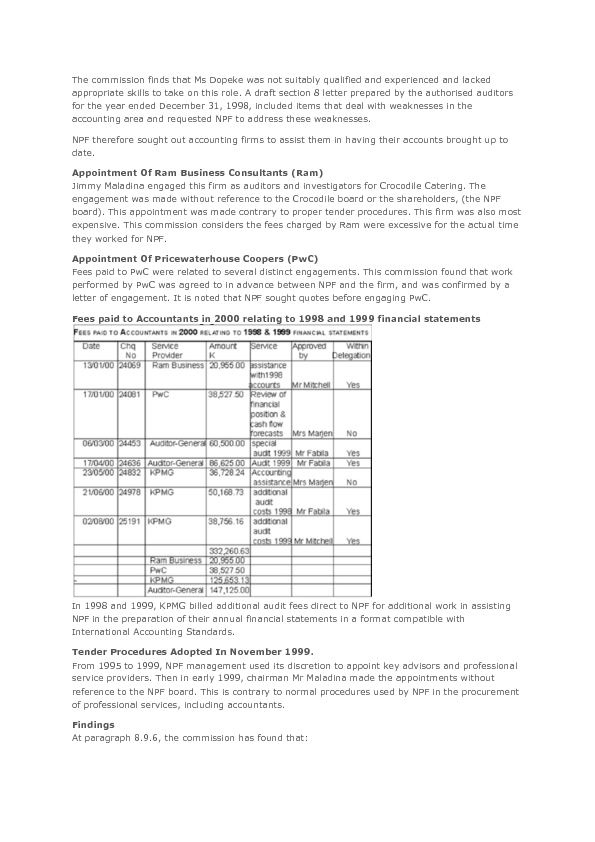

Appointment Of Ram Business Consultants (Ram) Jimmy Maladina engaged this firm as auditors and investigators for Crocodile Catering. The engagement was made without reference to the Crocodile board or the shareholders, (the NPF board). This appointment was made contrary to proper tender procedures. This firm was also most expensive. This commission considers the fees charged by Ram were excessive for the actual time they worked for NPF.

Appointment Of Pricewaterhouse Coopers (PwC) Fees paid to PwC were related to several distinct engagements. This commission found that work performed by PwC was agreed to in advance between NPF and the firm, and was confirmed by a letter of engagement. It is noted that NPF sought quotes before engaging PwC.

Fees paid to Accountants in 2000 relating to 1998 and 1999 financial statements

In 1998 and 1999, KPMG billed additional audit fees direct to NPF for additional work in assisting NPF in the preparation of their annual financial statements in a format compatible with International Accounting Standards.

Tender Procedures Adopted In November 1999. From 1995 to 1999, NPF management used its discretion to appoint key advisors and professional service providers. Then in early 1999, chairman Mr Maladina made the appointments without reference to the NPF board. This is contrary to normal procedures used by NPF in the procurement of professional services, including accountants.

Findings At paragraph 8.9.6, the commission has found that:

-

Page 14 of 190

-

(a) During the period January 1, 1995 to December 31, 1999, NPF engaged the services of the following accounting firms for various accounting and tax related services:

• Ernst & Young in the period 1995 to 1998 as tax agents and tax advisers; • Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu in 1999 as tax agents and tax advisers and to do sundry accounting services with regard to the Ambusa Copra Oil Mill Project; • PwC in 1999 as business advisers including inter alia a review of the fund’s investment portfolio and a review of the financial position at December 1999; • Ram in 1999 for accounting assistance (and in particular the completion of bank reconciliations for 1998); • Auditor-General — for the 1995 to 1997 financial years authorised auditor was Deloitte Touche and for 1998 to 1999, the authorised auditor was KPMG; (b) Almost without exception, NPF did not seek to tender the fund’s tax and accounting related work and as such NPF management failed to ensure the fund received the most cost effective service during the period 1995 to 1999;

(c) Following the departure of Mr Wright in January 1999, the weaknesses in the fund’s accounting systems and resources resulted in the need for the fund to out source accounting and business advice from the abovementioned professional accounting firms;

(d) These weaknesses in the accounting function also resulted in the significantly high level of additional audit costs levied by the authorised auditors, KPMG. In relation to the 1998 and 1999 financial statements, KPMG billed NPF direct contrary to normal procedures where audit fees are usually billed by the Auditor-General;

(e) With the exception of Ram, there is no evidence that favouritism or nepotism existed in the appointment of any of the professional firms. However, the lack of transparency and tender procedures in the appointment of these professional firms leaves a general suspicion that favouritism may have existed in relation to non-audit services, particularly with regard to Ram;

(f) There is considerable evidence connecting Rex Paki of Ram and Mr Maladina during the time that Mr Maladina and Mr Leahy were actively conspiring to defraud the NPF. Mr Paki also received benefits in the form of cash and airfares from the proceeds of those frauds;

(g) Examining the process of appointing Ram to provide services for NPF, the commission finds that it was similar to Mr Maladina’s improper appointment of Ram as financial consultant for Crocodile (see Schedule 3A);

(h) On all the evidence, the commission finds that the appointment of Ram by the NPF board, which was not properly briefed, was strongly influenced by Mr Maladina. Mr Maladina’s co- conspirator in the criminal conspiracy to defraud NPF, Herman Leahy, then proceeded to approve the payment of Ram’s excessive fees without seeking the required NPF board approvals.

(i) The commission finds that the appointment of Ram and the payment of their excessive fees on the approval of Mr Leahy constituted nepotism within the meaning of the commission’s terms of reference;

(j) There also exists a significant level of concern as to the probity or otherwise of fees charged by Ram. The limited documentary evidence in the form of the working papers, fees and correspondence files, produced under summons to this commission by Ram, to support the fees paid by NPF, indicates that the fees charged by Ram were excessive.

(k) Management acted in excess of their delegated financial authority by approving Ram’s fees without referring them to the board.

Other Professional Services During the period covered by this review (1995 to 1999), NPF hired other firms to carry out specific work requirements. These firms are:

-

Page 15 of 190

-

1. Hay Group of Companies; 2. Ken Yapane and Associates 3. Freehill Hollingworth and Page; 4. E&S Groups; 5. Minao Surveys; and 6. Sogu Works. The finance inspectors closely scrutinised the arrangements between NPF and the above firms and concluded they were in order, with the exception of Ken Yapane and Associates. The commission accepts and agrees with those findings.

National Provident Fund Final Report [Part 81]

Executive Summary Schedule 9 Continued Mt Tapi Brothers Mt Tapi Brothers Ltd (MTB) had associations with Mr Skate as it provided security services for the Prime Minister’s residence and family and for some of his Ministers. The telephone contact number MTB provided NPF was one of Mr Skate’s official numbers. Also at a later date, Mr Skate actively intervened on behalf of MTB (see below).

Mt Tapi Brothers Forceful Initial Approach On February 23, 1999, MTB offered to provide security for all of NPF’s properties. In its initial letter it pointed out its close connections with the Prime Minister and enclosed a draft contract. Mr Fabila received the letter on February 24, 1999 and immediately granted a contract to MTB, in the full knowledge that NPF was contractually bound to Metro and Kress.

On February 26, Mr Fabila wrote to Kress and Metro arbitrarily terminating their contracts as from February 28, enclosing cheques for payments due to that date.

Mr Fabila also wrote to MTB granting a 12-month contract, with a three-month probationary period. He then wrote to Century 21, which was still managing NPF properties, directing them to terminate any current security contracts for the investment properties and to make way for the new security guards to commence work from 1st March 1999.

Metro accepted the termination of its head office contract without a fight.

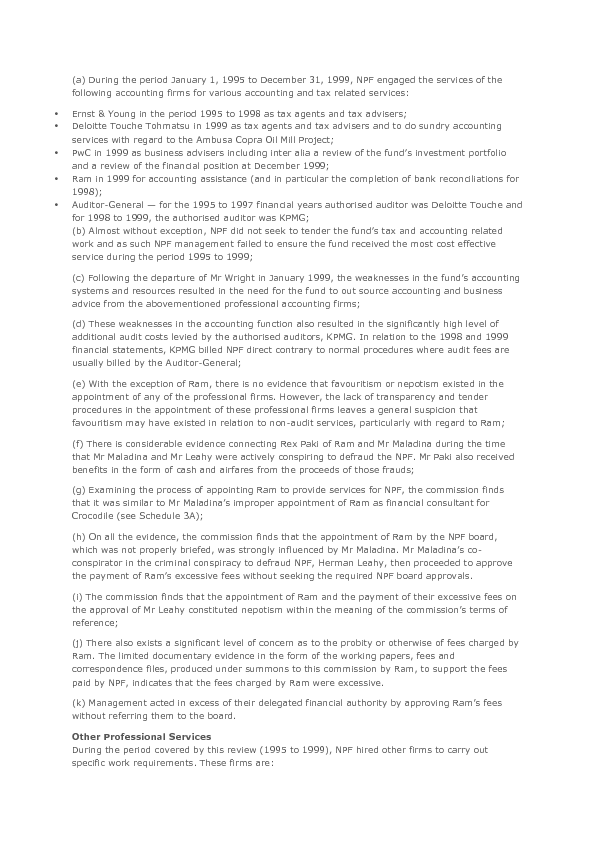

Kress on the other hand demanded K199,844.80 for wrongful termination of its contract. Kress received K8283.60 from NPF for the Nine-Mile properties for January and February and K22,754.40 for its other contracted properties prior to its contract being terminated. Its claim for breach of contract was eventually settled out of court for K40,684.80 (being three months payment in lieu of notice plus costs).

MTB Contract Mr Leahy prepared a contract on March 29, 1999 granting the security services for all NPF properties to MTB. The contract followed the draft presented by MTB with a few very minor amendments.

The first invoice for the period March 3, 1999 to April 7, 1999 was a phenomenally high K45,792, yet reports were being received that the service was very poor. When Mr Fabila complained about the exorbitant cost, the number of guards was cut from 52 down to 17. From March to August 1999 the complaints about the MTB security guards were pouring in.

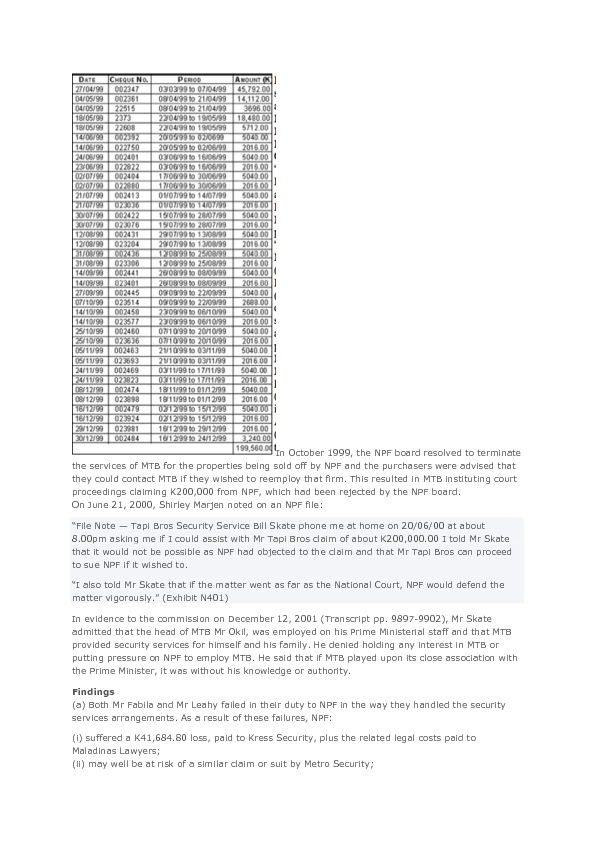

NPF records show that the following payments were made to MTB in 1999: (See table)

-

Page 16 of 190

-

In October 1999, the NPF board resolved to terminate the services of MTB for the properties being sold off by NPF and the purchasers were advised that they could contact MTB if they wished to reemploy that firm. This resulted in MTB instituting court proceedings claiming K200,000 from NPF, which had been rejected by the NPF board. On June 21, 2000, Shirley Marjen noted on an NPF file:

“File Note — Tapi Bros Security Service Bill Skate phone me at home on 20/06/00 at about 8.00pm asking me if I could assist with Mr Tapi Bros claim of about K200,000.00 I told Mr Skate that it would not be possible as NPF had objected to the claim and that Mr Tapi Bros can proceed to sue NPF if it wished to.

“I also told Mr Skate that if the matter went as far as the National Court, NPF would defend the matter vigorously.” (Exhibit N401)

In evidence to the commission on December 12, 2001 (Transcript pp. 9897-9902), Mr Skate admitted that the head of MTB Mr Okil, was employed on his Prime Ministerial staff and that MTB provided security services for himself and his family. He denied holding any interest in MTB or putting pressure on NPF to employ MTB. He said that if MTB played upon its close association with the Prime Minister, it was without his knowledge or authority.

Findings (a) Both Mr Fabila and Mr Leahy failed in their duty to NPF in the way they handled the security services arrangements. As a result of these failures, NPF:

(i) suffered a K41,684.80 loss, paid to Kress Security, plus the related legal costs paid to Maladinas Lawyers; (ii) may well be at risk of a similar claim or suit by Metro Security;

-

Page 17 of 190

-

(iii) paid the very large security bill for the period March 3 to April 7, 1999 (K45,792) which, as later costs show, was for services vastly in excess of NPF’s reasonable security service needs; and (iv) faces possible further risk in the pending litigation with MTB. (b) Mr Fabila and Mr Leahy face personal liability to NPF in relation to their failures outlined above which led to NPF’s loss. They would have great difficulties pleading a defence of “acting in good faith”;

(c) Mr Fabila and Mr Leahy disregarded the proper tendering process when engaging MTB;

(d) The commission finds that nepotism and political interference were operating in the actions of Mr Fabila and Mr Leahy in their handling and engagement of security firm MTB; and

(e) The action by Prime Minister Skate in telephoning Mrs Marjen on behalf of MTB was improper conduct. The commission recommends that the constituting authority refer this matter to the Ombudsman Commission to investigate Mr Skate’s conduct and his possible links to MTB to consider possible breaches of the Leadership Code by Mr Skate.

As MTB’s legal proceedings in the National Court against the NPF are still pending, the commission refrains from further comment about the roles of the various persons involved.

The finance inspector’s report, which examined and detailed irregularities in the security contracts, is summarised in paragraph 7.8.1. The finance inspectors focused on the failure to call tenders; failure to verify invoiced charges; advance payments; overpayments; extra legal amendments and failure to obtain the authority of the NPF Board of Trustees. The schedules to the finance inspectors report contain details of persons who authorised all the payments referred to and detailed calculations of the overpayments made to Kress Securities of K7632 (Schedules 3.1 and 3.2) and overpayments to MTB of K16,896 (Schedule 3.5). No attempt has been made by NPF management or the board to recover these amounts.

The commission records its agreement with the finance inspectors findings on these matters.

120th NPF Board Meeting At the NPF board meeting on September 29, 1999, Trustee Jeffery and Mr Mitchell asked detailed questions about the failure to tender security contracts; the termination of Kress and the appointment of MTB without competitive tenders. Mr Fabila’s answers were very unsatisfactory and it was resolved that:

“Resolution: “It was resolved that all security contracts adhere to proper tender procedures. It was further resolved: (i) THAT the vendor for each property sold be advised in writing after contracts of sale be exchanged and that security on the property then becomes the purchasers responsibility; (ii) THAT MT Tapi Brother be advised that their services are no longer required for each property when sold, however, allowing for the appropriate time for vendors to engage new security services; (iii) THAT NPF put out tenders for the Tower and remaining properties; (iv) THAT at the end of the property rationalisation that MT Tapi Brothers be given three months notice of termination.” (Exhibits N423-4) The now active NPF board held a special meeting on October 8, 1999 to consider a special report by Mr Jeffrey and Mr Mitchell. Mr Leahy was given time to answer searching questions. His reply, when it came, was evasive.

The changing of security arrangements in 1999 entailed breaches of contract and unnecessary cost to NPF. As corporate secretary, legal counsel and operations manager Mr Leahy had a duty to give proactive advice to Mr Fabila and the NPF board on these matters. He failed in that duty.

Findings

-

Page 18 of 190

-

At paragraph 7.8.4, the commission has found:

(a) NPF paid Metro Security K6830.20, Kress Security K8283.60 and MTB K199,560 for security services in 1999, aggregating K214,673.80. In addition, the payment of damages and legal costs made to Kress Security of K41,684.80, increased this total to K256,358.60 (It is necessary to deal with a single total, as the payments to MTB have not been split, in the commission’s calculations, between head office and other properties);

(b) The actual security costs included in the 1999 Income and Expenditure Account are; K223,223 for “Rental Property Expenses” and K54,542 for “Head Office Expenses”, aggregating K277,765. The difference of more than K21,000 cannot be explained by adopting a cash against accruals basis of calculation and the commission is not able to explain a difference of this magnitude;

(c) The decision by Mr Fabila to terminate the less costly services of Metro and Kress and to appoint the more expensive MTB was made in two days, without competitive bidding or advice. It cost NPF dearly in terms of:

(i) A payout to Kress of K41,684.80 for breach of contract; (ii) AN enormous initial bill of K45,792 from MTB for the first month for services, which were massively in excess of NPF’s actual needs; (iii) THE legal risk to NPF of a like wrongful termination suit from the second terminated contract; and (iv) litigation now pending before the National Court by MTB whose services, under a legally deficient contract, were also subsequently terminated. (d) MR Leahy was remiss in his duty in not proactively advising Mr Fabila against the foolhardy course on which he was embarking; (e) The contract awarded, without contest, by Mr Fabila to MTB Ltd was politically influenced by the close association with that company of Mr Fabila’s political appointer, the former Prime Minister Hon. Bill Skate and constitutes an example of nepotism in the award of that contract.

Concluding comments The commission concluded that:

“As with other topics in this report, it does seem that in 1994-5, both the NPF board and senior management appreciated the need to tender and obtain competitive bids for the provision of security services for the NPF Head Office and for the NPF properties rented to third parties.

Even then, when tenders were obtained and considered in March/ April 1995, there were competitive tenders for the rental properties only, but not for the head office. The board of trustees made the decision to contract in this instance.

Thereafter and until the end of 1999, all NPF security service contracts were let without tender and without any competitive bidding process and contrary to Government procedures for the procurement of services.

The board of trustees was only consulted once during this period — in October 1996 — over the change of security provider at NPF’s head office. On that occasion the board delegated the decision to management.

Otherwise, all other decisions about security services were made at management level.

The situation reached absurd proportions in February/March 1999 when Mr Fabila made a hasty decision to terminate the services of the two contracted security providers in favour of a single more expensive alternative — Mt Tapi Brothers Limited.

He did this without seeking advice or making inquiries and did so without referral to the NPF board”.

Procurement Of Accounting Services Background

-

Page 19 of 190

-

In house accounting capabilities during the period under review were as follows.

Noel Wright, a qualified Chartered Accountant who was originally employed as compliance manager, later became finance and investment manager and deputy managing director. He resigned from NPF in January 1999. He was replaced by Rod Mitchell who is not a qualified accountant. This was the time when NPF struggled to come to “grips” with its financial crisis.

Salome Dopeke was the chief accountant — she was a graduate accountant but had not passed all her PNGIA examinations and as such was not a formally qualified accountant.

It is therefore important to note that the accounting capabilities of NPF were weak and lacked professional efficiency and effectiveness. There were other specialised accounting requirements, which were outsourced to local accounting firms in Port Moresby.

Fees Paid To Accountants — 1995 Other than the above fees and audit related fees there were no external accounting fees incurred in 1995 and it is inferred all other accounting needs were satisfactorily handled in-house.

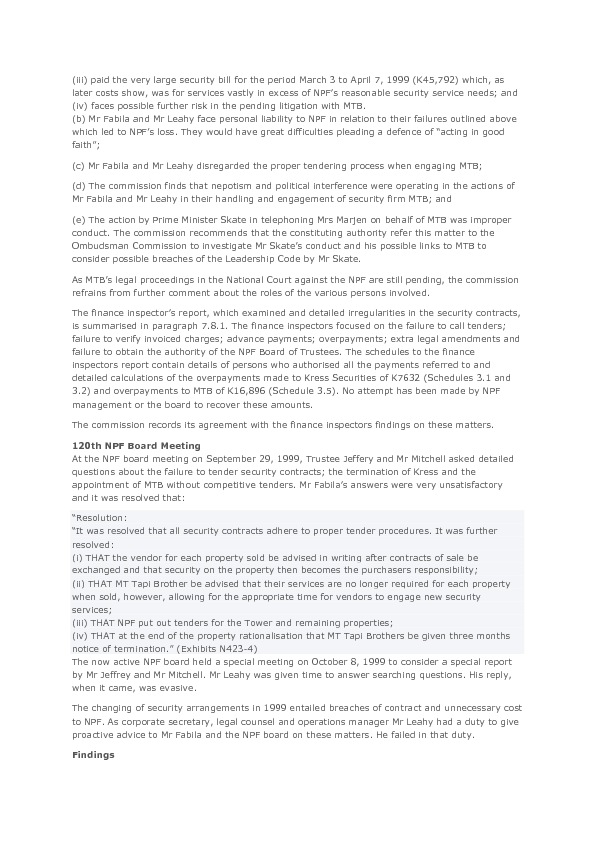

NPF utilised the services of the accounting firm Ernst & Young as tax agent from 1995 to 1998. There is no evidence of favouritism or nepotism in the appointment and continued engagement of Ernst & Young.

The audit of the financial statement of NPF is the responsibility of the Auditor-General’s office (AGO). In the case of NPF, the AGO subcontracted Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu to audit NPF’s accounts until the year ended December 31, 1997. There was scope for nepotism by NPF in this arrangement.

National Provident Fund Final Report [Part 80]

Executive Summary Schedule 9 Continued 1999 Outsourced legal fees for 1999 are reported in paragraph 6.4.7.

The state of the NPF records makes it difficult to separate fees for general work from investment related legal work so they are considered together.

The total comes to K442,648.12 plus $A871.90 paid to 11 different firms.

The massive amount of K202,023.46 went to Carter Newell (and an extra K17,602.58 described at paragraph 6.4.8).

Maladinas Lawyers was paid K17,653.50 for work which should have been handled “in-house”, including K5000 for fees relating to the Employers Federation challenge to Mr Maladina’s appointment, which should not have been paid by NPF at all.

Both large and small matters were briefed to Carter Newell in 1999.

Findings

-

Page 20 of 190

-

(a) Substantial fees were again paid to offshore legal firms in relation to the $A bond (Allen Allen & Helmsley) and the Cue Energy Resources situation (Freehill Hollingdale & Page) on the basis of their complexity and the need for specialised legal expertise;

(b) Fees paid domestically for board restructure advice (from Allens Arthur Robinson) and some of the work referred to Maladinas, Fiocco Posman & Kua and Carter Newell, were properly outsourced because of the complexity and the need for specialised legal expertise;

(c) There is insufficient detailed evidence to enable the commission to comment on matters referred to other firms;

(d) There is a discernable trend whereby more work was referred out to external lawyers, which should have been capably handled by NPF’s “in-house” lawyers; and

(e) The level of fees suggests that matters of lesser significance were also referred to Pattersons, Henaos and Young & Williams.

The commission summarises the evolving situation regarding outsourcing legal frees at paragraph 6.5.

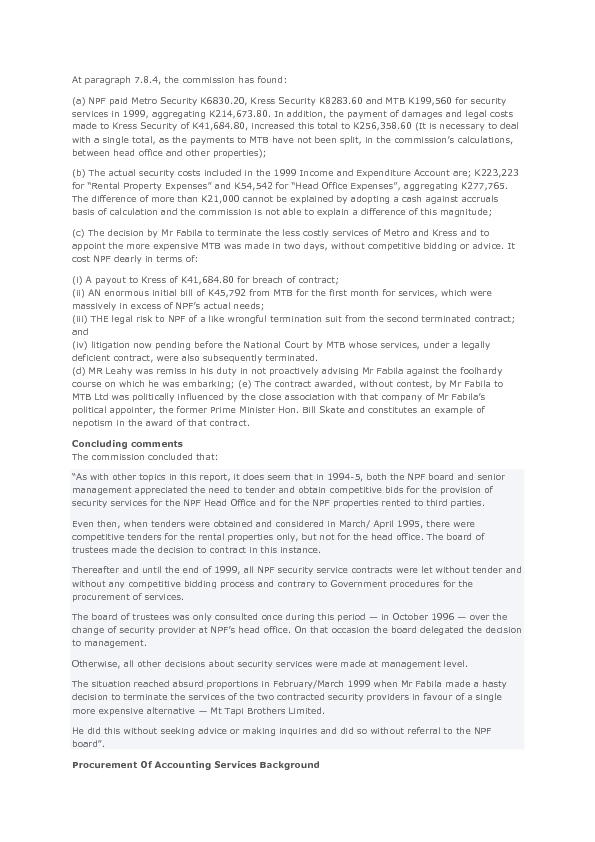

Summary In the period under consideration, external legal fees paid by NPF for work outsourced grew in the period under review as follows:

To a very large extent, the massive increases in 1998 and 1999 reflected the need to obtain expert and specialised advice in relation to legal transactions in which NPF became involved.

It is equally apparent that there was an increasing trend to brief out to external lawyers matters, which should have been within the competence of NPF’s “in-house” legal staff. This was reflected in the legal fees paid in 1998 and 1999.

The clear major beneficiary of that trend was Carter Newell Lawyers and, to a lesser extent, Fiocco Posman & Kua and an even lesser extent, Maladinas.

At paragraph 6.4.8.12, we said there may have been further legal fees paid to Blake Dawson Waldron and Carter Newell after August 31, 1999 and that this might explain the difference of about K21,000 in fees referred to on that page.

Additional payments From NPF’s cheque payment records, the commission further extracted the following payments, which were made after August 31, 1999, and not included in earlier material.

Gadens Lawyers (Adding to paragraph 6.4.8.1 and Transcript p.7589) A payment of a further K2342.95 was made on December 21, 1999 for advice for Ambusa on its copra oil purchase and sales agreement and operations management contract.

Blake Dawson Waldron (Adding to paragraph 6.4.8.6 & Transcript p.7592) Two further payments were made:

(a) on November 8, 1999, for K9995.56 for advice as to a dispute with Boroko Motors; Pacific Finance Superannuation Fund; debt restructure and a review of Garry Jewiss’ contract with Crocodile Catering;

-

Page 21 of 190

-

(b) on December 6, 1999, for K26,743.77 payable to Blake Dawson Waldron Melbourne Australia office, for advice on the sale of shares in Cue Energy Resources.

Carter Newell (Adding to paragraph 6.4.8.7 and Transcript p. 7595) Three further payments were made:

(a) on November 8, 1999, for K6048.04 for advice as to exemptions under Part VII of the NPF Act and for Mr Mitchel’s employment contract;

(b) on December 2, 1999, for K4087.79 for advice on NPF’s Investment Portfolio involving Deutsche Morgan Grenfell; and

(c) on December 21, 1999, for K7466.75 for advice and work done on the sale of shares to NPF in Kundu Catering; general matters on NPF Tower leasing and a claim by Cue Energy Resources.

The supporting vouchers and invoices are Part M of CD1226. The aggregate of these further payments was K56,648.56 and results in the difference of K21,000 becoming an excess of K25,000.

The commission’s accounting advisors have stated that this difference is probably explained by the manner in which NPF has treated the VAT component in the payments made.

Investigations In late 1999, the finance inspectors and then the NPF board itself, carried out inquiries into irregularities concerning Mr Maladina and Mr Leahy which included questions about their conflict of interest in briefing legal work to Carter Newell, in which firm Mr Maladina was a partner and Mr Leahy’s wife, Angelina Sariman, was employed.

Although their clear conflict of interest was raised with them, Mr Maladina and Mr Leahy vigorously denied any conflict. Failure to put legal outsourcing out to tender was not, however, raised by the inspectors.

As reported in paragraph 6.6.3, NPF started to brief Carter Newell only after Ms Sariman commenced work with that firm. She was recorded as the work author for 46 of the first 50 new files Carter Newell opened for NPF.

A calling for tenders for legal work was belatedly raised in October 1999 by Mr Giregire and an advertisement was placed in the newspapers.

Findings (a) Mr Leahy’s conflict of interest regarding outsourcing legal services to Carter Newell is clear. When Mr Leahy briefed out work to this firm where his wife was employed as a lawyer. This amounted to nepotism.

(b) When Mr Maladina became chairman of the NPF Board of Trustees, a further conflict of interest clearly arose, as he was also a partner in Carter Newell;

(c) When Mr Leahy referred legal work to Carter Newell, of which the chairman, Mr Maladina, was a managing partner, it was clearly nepotism. This was also improper conduct by Mr Leahy and a breach of his common law duty to the NPF board;

(d) Mr Maladina never declared his conflict of interest to the board of trustees. This amounted to improper conduct and a breach of his fiduciary duties to the members of the fund;

(e) Mr Maladina, as an equity partner in Carter Newell, benefited from legal work being referred by Mr Leahy to Carter Newell;

(f) Mr Leahy benefited by having his wife employed and continuing to be employed for reward by that firm;

-

Page 22 of 190

-

(g) Paying overseas law firms through NPF’s account with Wilson HTM Brisbane, breached the BPNG Foreign Currency Exchange Act and was therefore illegal; and

(h) Management breached normal government tender procedures by not going out to public tender for the provision of legal services.

Procurement Of Security Services Pre-1995 The commission’s terms of reference requires it to examine the procurement of security services for the period commencing January 1, 1995 until December 31, 1999. To understand the situation at the beginning of 1995, however, it is necessary to look briefly at earlier events.

Awarding and terminating NPF’s contract with Kress Securities On October 7, 1993, Mr Kaviagu, the NPF financial controller, awarded a contract to Kress Security Services beyond the scope of his delegated authority and without following proper tender procedures and evaluation. On December 8, 1993, Mr Kaul issued a memorandum directing that tenders for security services must be submitted to him, with recommendations, for his approval.

On December 21, 1993, Mr Kaul declared the Kress contract to be null and void and put the contract out for be re-tender. Kress refused to tender but sued NPF for breach of contract instead. This matter was eventually settled out of court, with NPF awarding a 12-month contract to Kress, (plus K4000 damages in March 1994), for all NPF’s investment properties except head office. NPF also paid K4000 to Kress in damages.

1995 Thus, at the commencement of the period under review, on January 1, 1995, there were two security firms contracted to NPF.

• Moresby Guards — head office; and • Kress — all other properties. The contracts were to expire in March 1995 and tenders were called from a list of firms. The only tender received for the head office was from Moresby Guards. Kress was the lowest of five tenderers for the other properties.

At the NPF board meeting on April 27, 1995, Kress was awarded the contract for all properties, including head office, at a cost per guard of K14,892 per annum.

Findings (a) The only security contract let in 1995 was to Kress Security for all NPF properties. Tenders were called and Kress Security was the lowest tenderer. Only one tender was received for NPF head office security and no competitive bids were sought, even from Kress Security. There was non-conformity with prescribed tender procedures but it seems clear that the rate offered by Kress Security was the lowest;

(b) The NPF Board of Trustees was clearly informed and involved and itself made the decision to contract Kress Security.

1996 Kress Security was the only security provider for all NPF’s properties throughout 1996, however, Mr Kaul became dissatisfied with Kress’ performance at the head office.

On July 29, 1996, Mr Kaul received a letter from a firm called Metro Security Services Pty Ltd with a proposal to provide security at a cheap rate of K1.70 per hour. Without performing any due diligence, Mr Kaul then recommended to the NPF board that Metro Security replace Kress at head office. At the 103rd board meeting, on October 10, 1996, the Board resolved:

“to replace the current security service with another security service organisation to be decided on by the management”.

This was a full delegation of its role in this matter to management.

-

Page 23 of 190

-

On October 25, 1996, Mr Kaul gave Kress three months notice, terminating its head office contract from January 26, 1997. He expressly assured Kress it would continue to provide security for NPF’s other properties.

The commission has examined records of the payments to Kress throughout 1996 and finds that they were in order. The details are set out at paragraphs 7.4.3.1 and 7.8.3.2.

Findings (a) The amounts paid to Kress Security for head office security services in 1996 was K29,142.80. This compares to the figure shown in the 1995 Income and Expenditure Statement and the same figure for the comparables in the like statement for 1997;

(b) The amount shown by Century 21 statements for rental property security in 1996 was K148,226.41 as against K149,491 shown in the Income and Expenditure statements. Again, the minor differences are probably explained by the fact the commission’s figures are on a cash basis and those in the Income and Expenditure statements were probably made on an accruals basis; and

(c) No new security contract was actually let in 1996, but after being fully informed the NPF board delegated the decision to management.

1997 Contract with Metro Mr Kaul awarded the head office contract to Metro on November 19, 1996, to commence on January 26, 1997. Mr Frank then wrongly drafted the contract to also include five other NPF properties over which the Kress contract was still in force. This resulted in double security for some weeks until Metro agreed to withdraw from the extra properties on payment by NPF of K4694.75 compensation.

The commission’s research into payments for security in 1997 is set out at paragraphs 7.5.4, 7.5.5, 7.5.6 and 7.5.7. There appear to be no anomalies except two unexplained payments totalling K11,800 to a company named Phantom Security Services Pty Ltd. No invoices exist for this alleged service. The documents show that Mr Leahy was involved in this matter.

Findings (a) Tender procedures and requirements were totally ignored by NPF management in the letting of security services in 1997;

(b) The amounts paid for head office security in 1997 were K5395.80 to Kress Security and K35,770.95 to Metro Security aggregating K41,166.75. This compares to the figure shown in the 1997 Income and Expenditure statement of K38,593 and the same comparable figure in the like statement for 1998;

(c) The amounts paid for other security services were Kress Security K11,372.40 (for Nine-Mile) and Phantom Security K11,800 for the Kaubebe St property plus the amount shown in the Century 21 statements for rental property security in 1997 of K150,112.80 aggregating in all K169,435.20. This matches the figure shown in the 1997 Income and Expenditure statement of K169,435 and the same comparable figure in the like statement for 1998;

(d) The only changes which took place in the area of continuous security work in 1997 were:

(i) Metro Securities replacing Kress Security as the provider of security at the NPF head office; and

(ii) Kress Security being given additional security work at Nine- Mile housing project.

(e) No tenders were called in 1997 to provide security and there was no competitive bidding obtained for either of the changes in (c) above; and

-

Page 24 of 190

-

(f) There was no competitive bidding for the “one-off” job of “Eviction/Demolition” for which Phantom Security was paid.

1998 This was a stable year in security services. Metro continued to provide security services for the head office throughout 1998 for a total fee of K51,246 and the payments disclose no anomalies.

Security services for all other NPF properties were provided by Kress. Kress received the sum of K145,702 through Century 21 for providing this service.

Findings (a) The amount paid to Metro Security for NPF head office security in 1998 was K31,905.60. This matches the actual figure of K31,906 shown in the 1998 Income and Expenditure statement but not the comparative figure of K33,361 shown in the statement for 1999. The probable reason is that the latter figure for the second half of December 1998 was probably included even though it was paid in 1999; and

(b) The amount paid to Kress Security for all other security services in 1998 was K145,702.

1999 As previously discussed in paragraphs 3.4.1 – 3.4.5, 1999 was the year when NPF property management services were totally restructured with the termination of Century 21’s long standing exclusive management contract.

This was replaced by the awarding of contracts to Gemini and Haka and the lucrative NPF Tower contract to PMFNRE.

This process was marked by Mr Leahy’s interference in the competitive tendering process, which Mr Fabila accepted and facilitated.

1999 was also the year when Mr Maladina was appointed chairman of NPF at the instigation of the then Prime Minister Hon Bill Skate and it was the year when Mr Maladina and Mr Leahy pursued fraudulent schemes against the NPF with the knowledge and acceptance of Mr Fabila.

These same lawless tendencies also characterised the arrangements for security services in 1999.

National Provident Fund Final Report [Part 79]

Executive Summary Schedule 9 Continued Property mentioned at the 99th NPF Board meeting The property was mentioned at item 5.10 of the minutes of the 99th NPF Board meeting on 23rd February 1996 but not in relation to the proposed sale to Mr Paska, which was consequently not discussed at Board level.

Mr Paska contracts to buy Mr Leahy prepared a contract of sale and forwarded it to Mr Paska who signed the contract and returned it to the NPF Managing Director, Mr Kaul, on 6th December 1996, saying he had rented the property to tenants and that all rent collected would be remitted to NPF. He said that he was anticipating final settlement 2 weeks from the date of his letter.

Mr Paska makes part payment and seeks Ombudsman Commission approval There was some delay while Mr Paska sought to obtain a bank loan but, meanwhile, he paid K24,000 to NPF on 10th July 1997 as a deposit on the purchase.

On the same day, he wrote to the Ombudsman Commission seeking approval to buy the property. He stated that the NPF Board had “approved consideration of my interest in acquiring the

-

Page 25 of 190

-

property”. He also said he had obtained legal advice that there was no conflict of interest. Mr Paska did not advise the Ombudsman Commission that he had already signed the contract of sale and been receiving rent on the property since December 1996 and that he had paid K24,000 towards the purchase price.

Mr Leahy communicates with Ombudsman Commission On 11th July 1997, Mr Leahy wrote to the Ombudsman Commission in support of Mr Paska, saying that following his expression of interest, Mr Paska had been asked to make an offer to the Board and that he had offered K96,000. Mr Leahy falsely said that this offer had been approved by the Board in Mr Paska’s absence. At this stage, the Board had not considered Mr Paska’s offer.

During early August, the Ombudsman Commission sought details from Mr Leahy of the Board resolution approving the sale to Mr Paska (These inquiries were followed up by a formal letter on 22nd August 1997). As there had not yet been such a resolution, Mr Leahy proceeded to manipulate the NPF Board in order to bring such a resolution into existence.

Mr Leahy manipulates NPF Board to retrospectively create a resolution approving the sale to Mr Paska The NPF Board held its 108th meeting in Kavieng on 22nd August 1997, and it seems as though a late item was introduced, orally, as there was no mention of it in the pre-prepared management papers. The item sought to amend the minutes of the 99th Board meeting held some 18 months earlier on 23rd February 1996. This meant that Item 5.10 of the earlier minutes was replaced with a new item 5.10 that purported to describe how Century 21 had been listing the property for K110,000, that there were interested buyers but “the sale price appeared to be beyond market valuation”, that an offer of K96,000 to purchase from Mr Paska was tabled and discussed by the Trustees to ensure it was fair market value and that it was resolved to accept Mr Paska’s offer (Century 21 later refused to confirm its alleged role as stated in the amended minute).

It is recorded that the Board resolved at the 108th meeting to approve the amendment to item 5.10 of the minutes of the 99th meeting and that Mr Paska was not present during the 108th meeting.

Mr Leahy provides misleading statement to the Ombudsman Commission In answer to the Ombudsman’s letter of 22nd August 1997, Mr Leahy replied on 23rd September 1997, enclosing a signed extract of item 5.10 of the minutes of the 99th NPF Board meeting held on 23rd February 1996. The extract was certified by Mr Leahy on 23rd September 1997, as if it were an item recorded at the 99th meeting on 23rd February 1996.

The item so certified, was the amended item, which had been resolved on the 27th August 1997, at the 108th Board meeting.

Quite clearly, this was a false representation deliberately designed by Mr Leahy to deceive the Ombudsman Commission. Mr Leahy’s conduct was unprofessional. This Commission has recommended that he be referred to the President of the Papua New Guinea Law Society and the Ombudsman Commission for further investigation.

Mr Paska withdraws offer to purchase and PNGTUC becomes the purchaser Despite these false representations designed to encourage the Ombudsman to approve the sale to Mr Paska, the Ombudsman Commission still delayed its ruling. Mr Paska then withdrew his offer to purchase the property at the 110th meeting on 11th December 1997. He requested that the sale be made to the PNGTUC instead for K96,000. Mr Paska, who is the General Secretary of the PNGTUC, was present at that meeting and did not declare his conflict of interest.

Delay in executing contract PNGTUC paid a deposit of K9,600 in February 1998 and remained in possession of the property receiving rent for it. Despite considerable correspondence between NPF and PNGTUC and exchange of documents, the contract was not finally executed until 6th November 1998. This was an

-

Page 26 of 190

-

extraordinary long delay, considering that the PNGTUC had already been allowed to take possession (which was highly irregular) and was receiving rent for the property.

The settlement of this transaction was continually postponed as the PNGTUC experienced difficulty securing the required financing. Meanwhile, however, the rent received accumulated and they enjoyed the benefit of it.

On 18th September 2000, NPF’s new legal counsel, Mr Kamburi, issued a “Notice to Complete Settlement” to PNGTUC. On 11th October 2000, PNGTUC responded that K61,950 had been collected in rent, that K4,000 had been spent on improvements and K52,000 was held in trust. PNGTUC (unsuccessfully) sought a rent sharing agreement with NPF.

The sale was finally settled on 20th October 2000 and PNGTUC paid the full balance of the K96,000 purchase price. There had been no independent valuation of the property and the 1995 proposed purchase price of K96,000 had not been reassessed during the 5 years to the settlement date.

Reluctant payment of rent by PNGTUC On 10th January 2001, after NPF had instituted legal proceedings, PNGTUC paid NPF K50,000 of the rentals they had previously collected. The letter enclosing the bank cheque for that partial rent payment concluded:

“the balance will most probably be in the vicinity of K10,000 – K15,000 … Hopefully this amount will be settled sooner rather than later”.

Findings (a) The disposal of Allotment 13 Section 73 Korobosea failed to comply with Government tender procedures. The Board and management staff may be held responsible by members of the Fund for any loss incurred in the sale of this property.

(b) No valuation of the property was made to determine the commercial value of the property.

(c) The sale of this property to PNGTUC and the conduct of NPF management in their handling of this sale in the face of Mr Paska’s conflict of interest was nepotistic and improper.

(d) Although Mr Paska had previously declared his conflict of interest as a Trustee and contracted purchaser, he was also General Secretary of the PNGTUC but did not abstain from discussing on the sale of this property to PNGTUC and was therefore in a conflict of interest situation.

(e) The long delay in completing the conveyancing enabled PNGTUC to rent the premises and receive K61,000. NPF instituted legal proceedings against PNGTUC. In January 2001, PNGTUC still owed between K10,000 – K15,000 to NPF.

(f) Mr Leahy engineered the approval by a new Board resolution on 22nd August 1997, which created a substitute minute of the meeting of 23rd February 1996 intending to mislead the Ombudsman Commission. He should be referred to the PNG Law Society to consider whether disciplinary measures should be imposed upon him.

(g) The Ombudsman Commission should be notified about the events leading up to the amended Board minute, which was created specifically to mislead the Ombudsman Commission. They should be asked to consider whether an offence has been committed and / or whether there is a gap in the legislation, which may require legislative amendment.

Concluding comments Mr Paska’s initial expression of interest to purchase the property was done openly and he disclosed his conflict of interest in a frank and refreshing manner. Based on his own evidence to the Commission and on the evidence of contemporaneous documents produced, he was acting honestly and transparently, though he was clearly not aware of the law of Trusts.

-

Page 27 of 190

-

At that stage, Mr Leahy should have pointed out that it would be inappropriate for Mr Paska as a Trustee to buy any portion of the Trust property and it would amount to a breach of fiduciary duty by Mr Paska and a breach of duty by management to sell it to him.

In any event, it would have been particularly necessary, in these circumstances, to get an independent valuation and to advertise for tenders. Instead, Mr Leahy struck a purchase price based on the land and construction costs and prepared contract documents, without doing either and without referring the matter to the Board. Mr Paska was allowed into possession before executing the contract documents, well before settlement took place. He then rented out the property taking the benefit of the rent for himself. It would have been a simple and inexpensive procedure to have placed an advertisement calling for tenders at that time, but that was not done.

Mr Paska’s disclosure to the Ombudsman was not complete and Mr Leahy’s manipulation of the NPF Board to be able to provide the Ombudsman Commission with a “manufactured” resolution apparently approved 18 months earlier in February 1996, was improper.

When Mr Paska withdrew from the purchase in December 1997 and “handed it on” to the PNGTUC as purchaser, he ignored the fact that he remained in a position of conflict as a Trustee of NPF (the vendor) and general secretary of the PNGTUC (the new purchaser).

The fact that the NPF management and Trustees allowed the completion of the settlement to drag on until 20th October 2000, with rent of K61,000 accumulating in PNGTUC’s hands, was a very serious beach of common law and fiduciary duty to the members of the Fund. That this neglect of duty was occurring in favour of Trustee Paska, initially as purchaser and then as secretary general of the substituted purchaser, was nepotistic and improper conduct.

PROCUREMENT OF LEGAL SERVICES The Commission makes a detailed analysis of NPF’s “in-house” legal service capacity from January 1995 through to December 1999, noting that there were always two full time “in-house” lawyers and sometimes three. Having studied the individual experience and capabilities of the “in-house” lawyers employed during the period, the Commission concludes that throughout this entire period, NPF had the capacity to carry out all routine PNG domestic legal work, “in-house”. There was, however, always the need to brief out work of more complexity or involving specialist skills or international connections.

NPF had no system or practice of monitoring the legal work briefed out to external lawyers or of calling for tenders. It was simply left to Mr Leahy’s discretion.

Outsourced legal services during 1995 & 1996 The study each matter outsourced to each firm, year by year.

For 1995 and 1996, outsourcing was modest and justifiable, considering the nature of the matters outsourced.

1997 Analyses outsourcing of general matters and investment related matters. Outsourcing of general matters was very modest and mostly, appropriate.

Findings The Commission has found:-

(a) The general pattern for legal fees in 1997 was to outsource complex matters or those matters requiring specialised legal expertise.

(b) Goroka matters were briefed out to Pryke & Co.

(c) Fees paid to Warner Shand and for a ‘lost certificate’ to Carter Newell, should have been handled “in house”.

-

Page 28 of 190

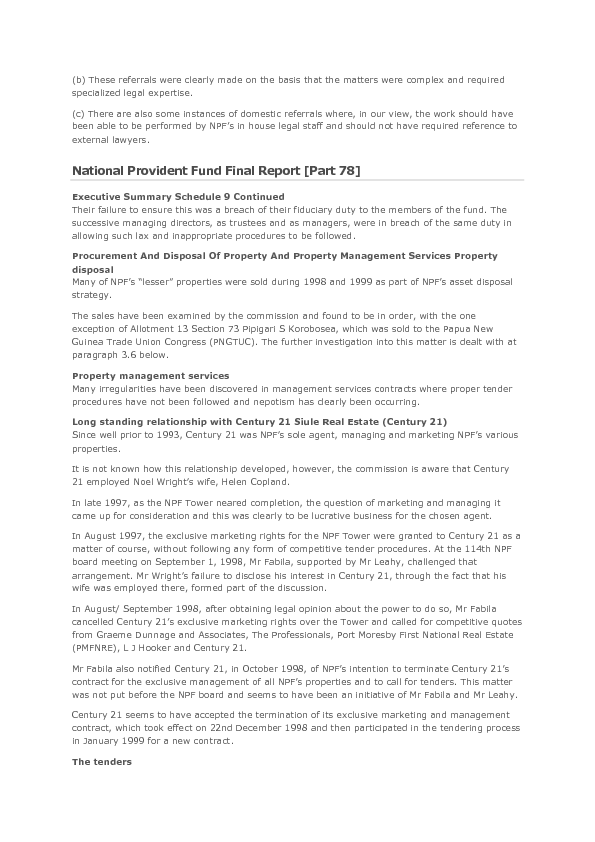

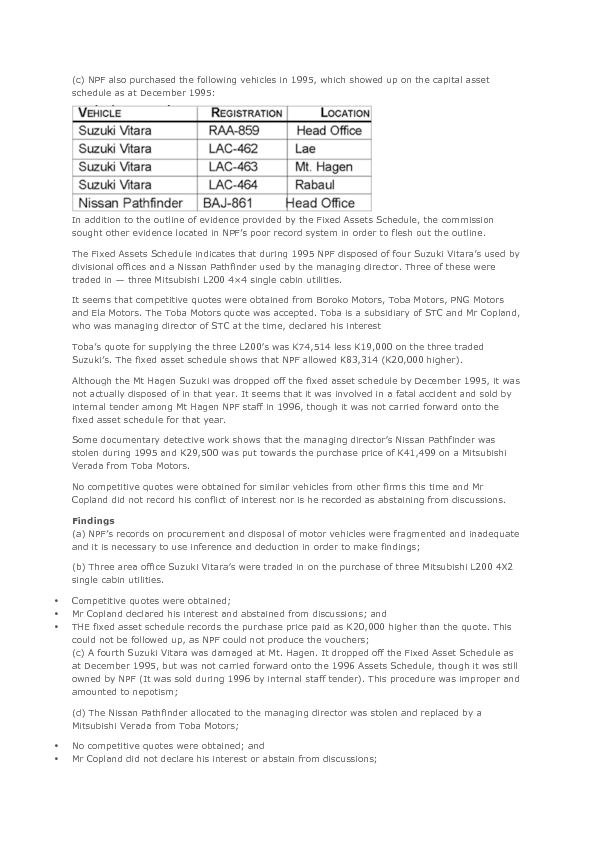

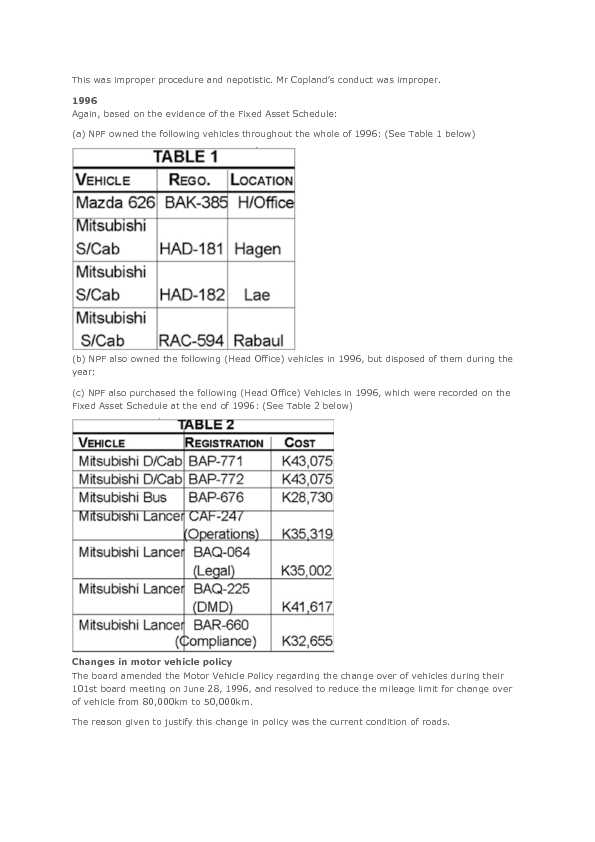

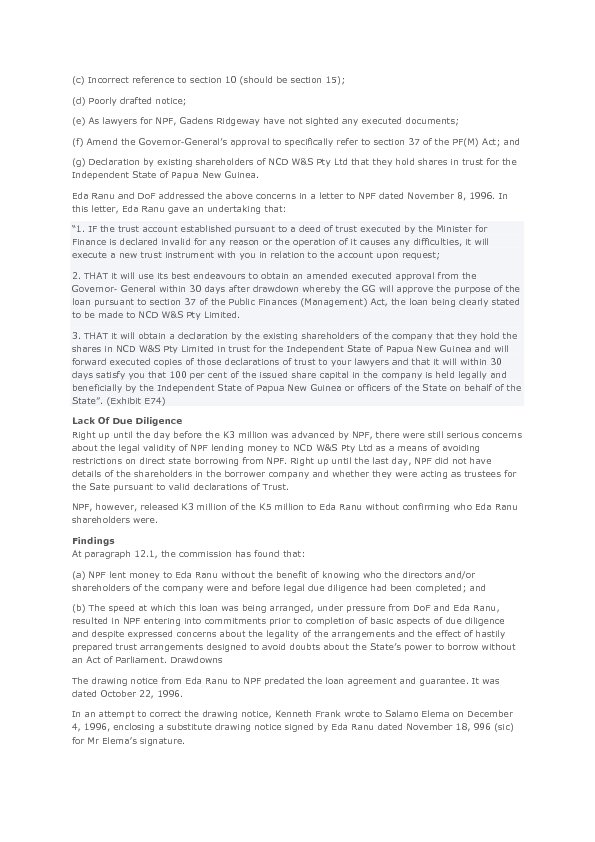

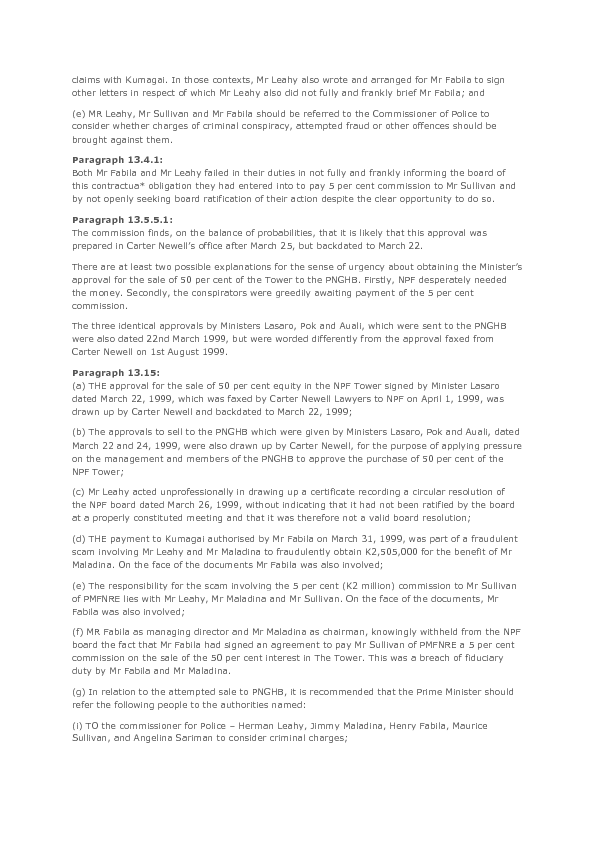

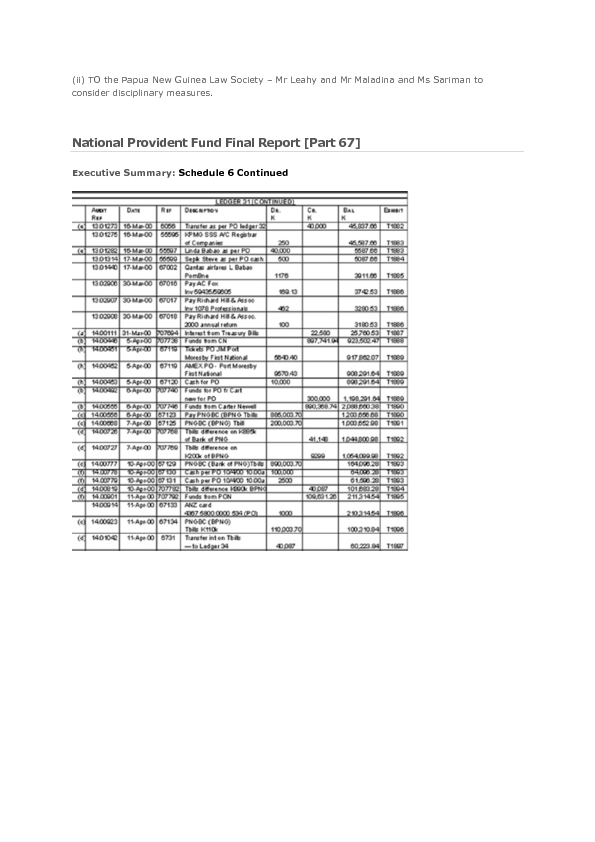

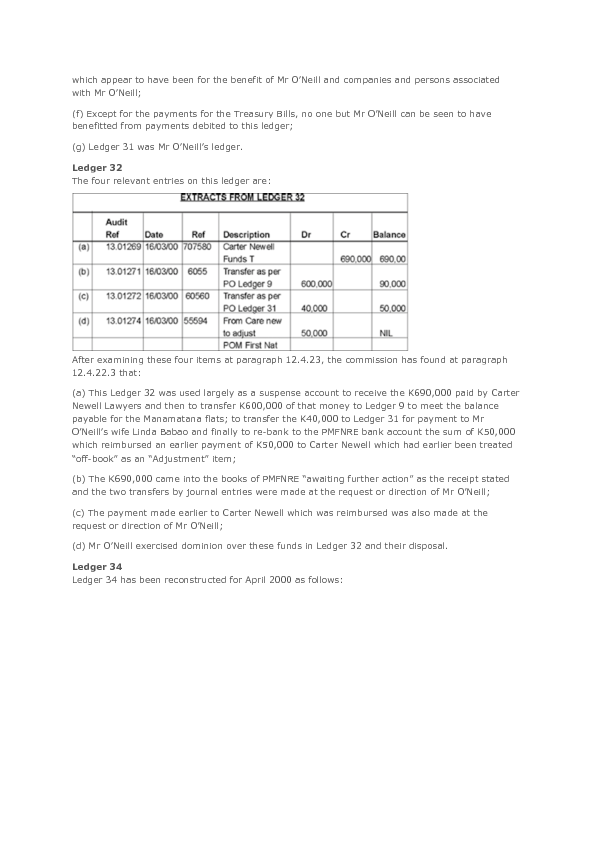

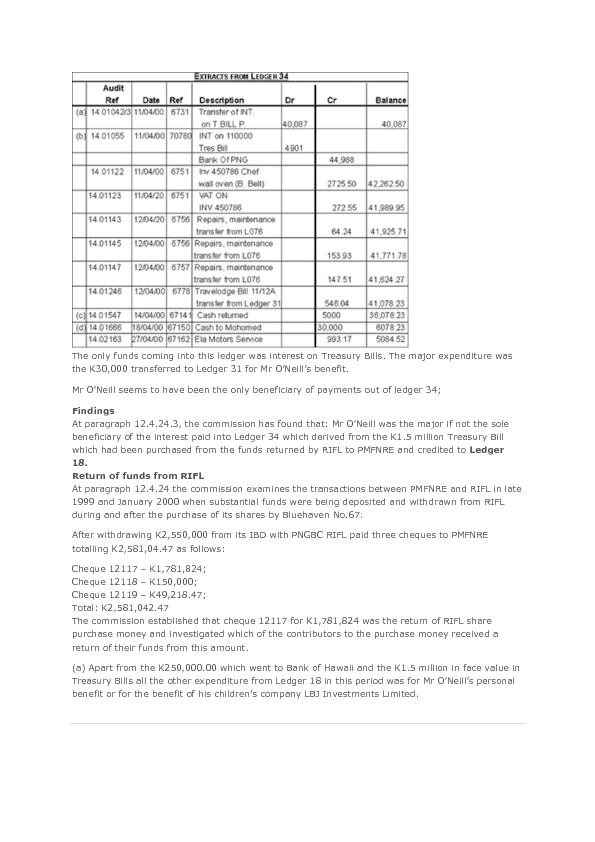

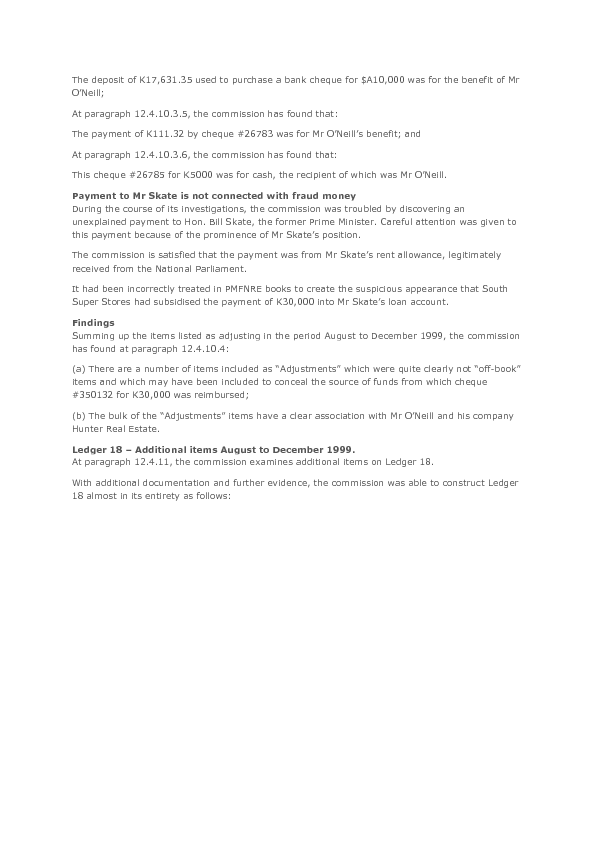

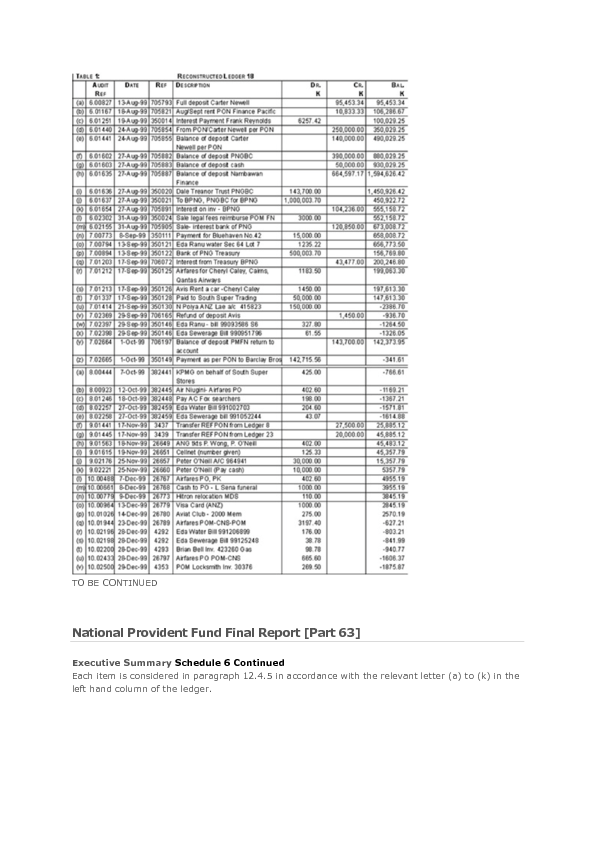

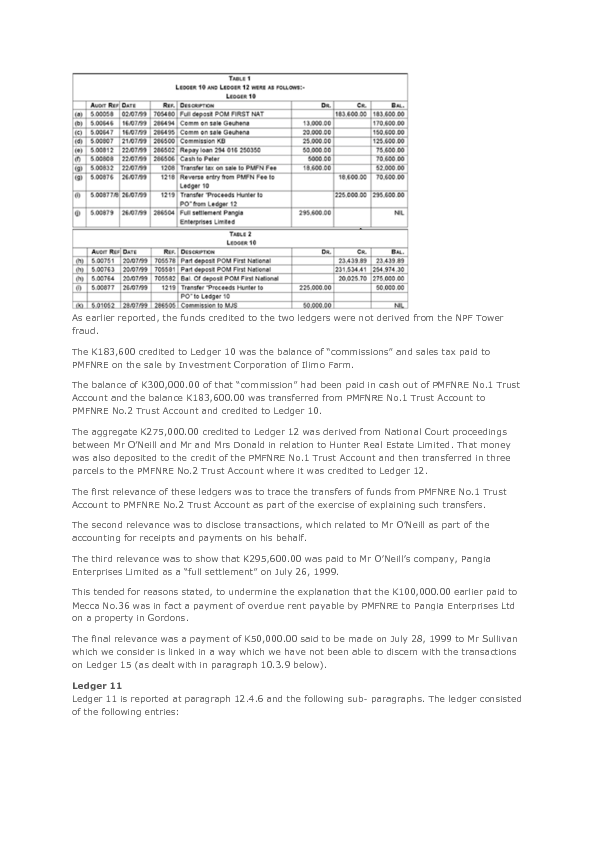

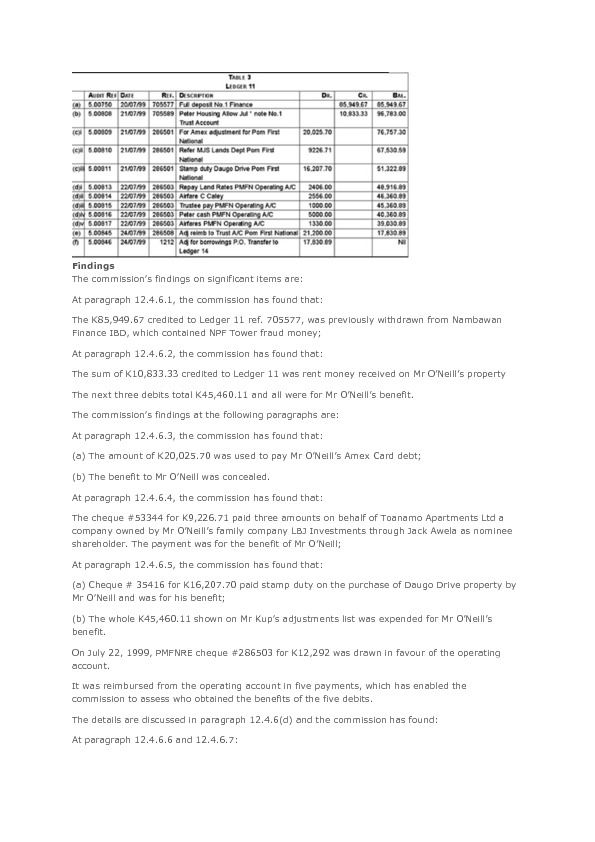

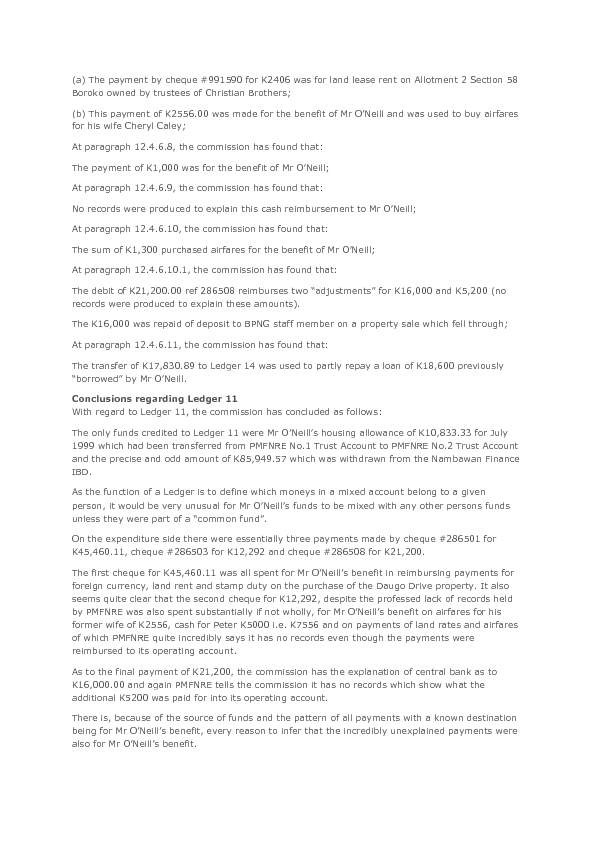

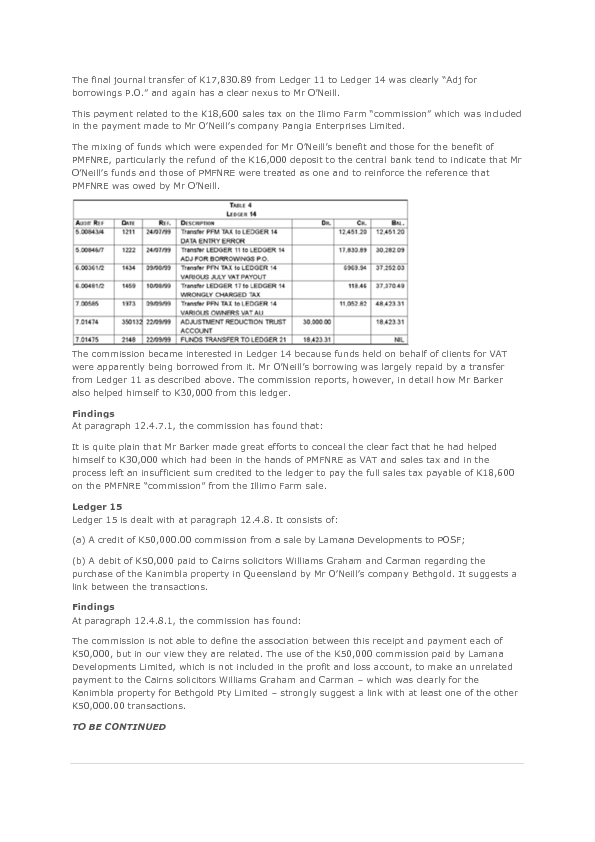

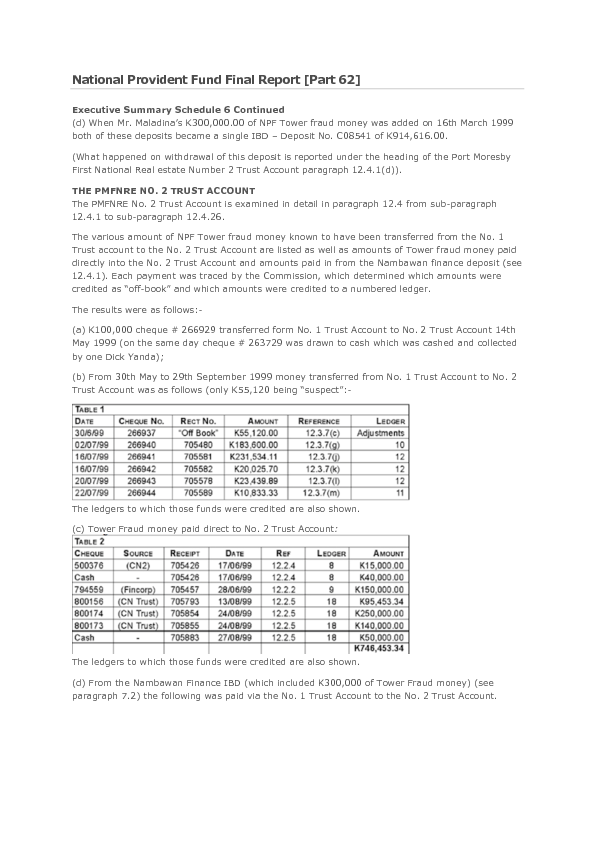

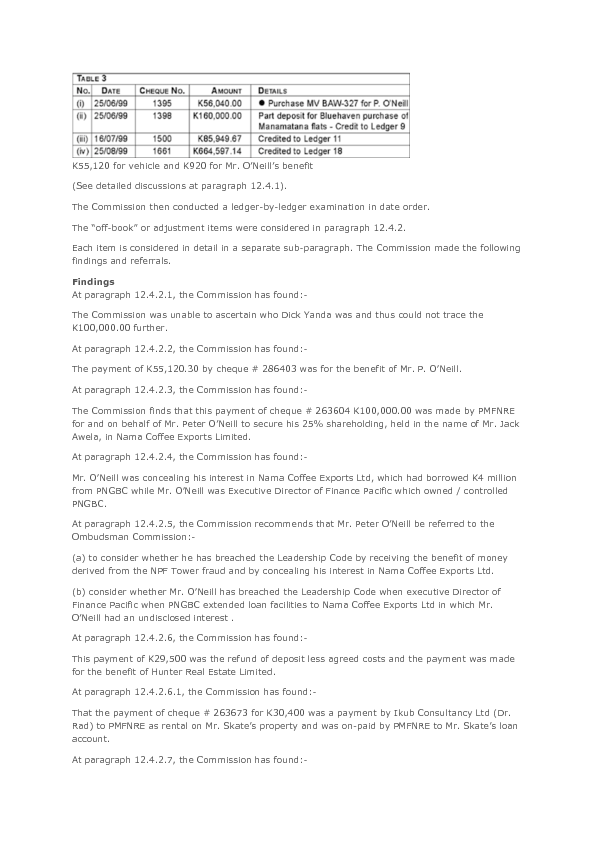

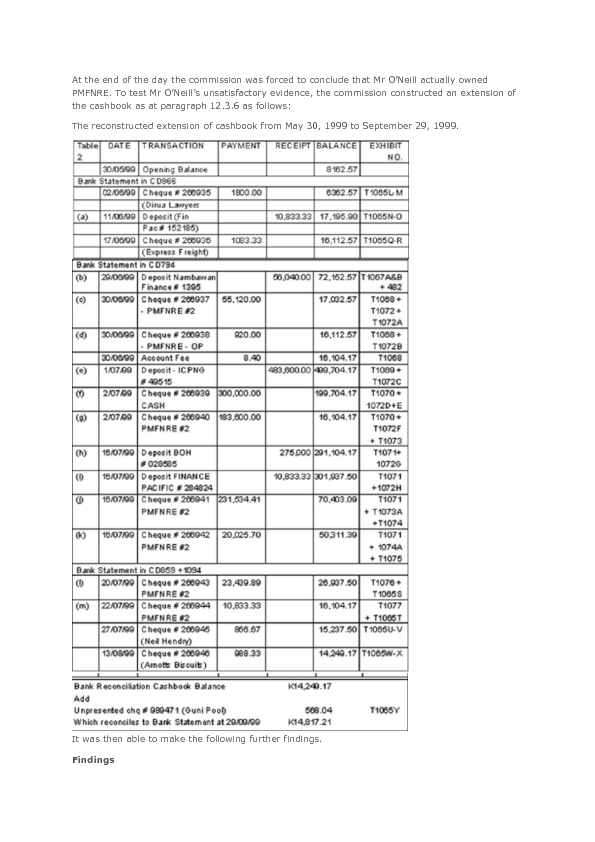

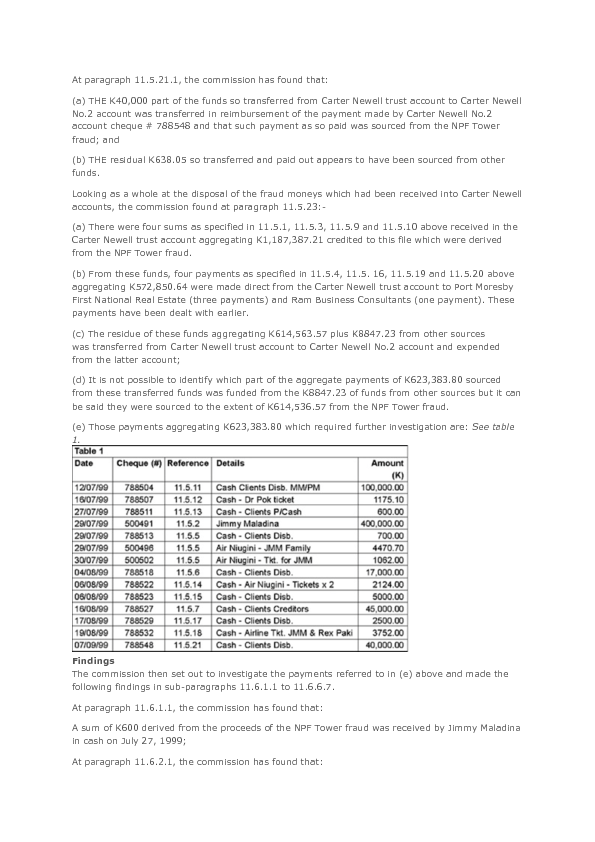

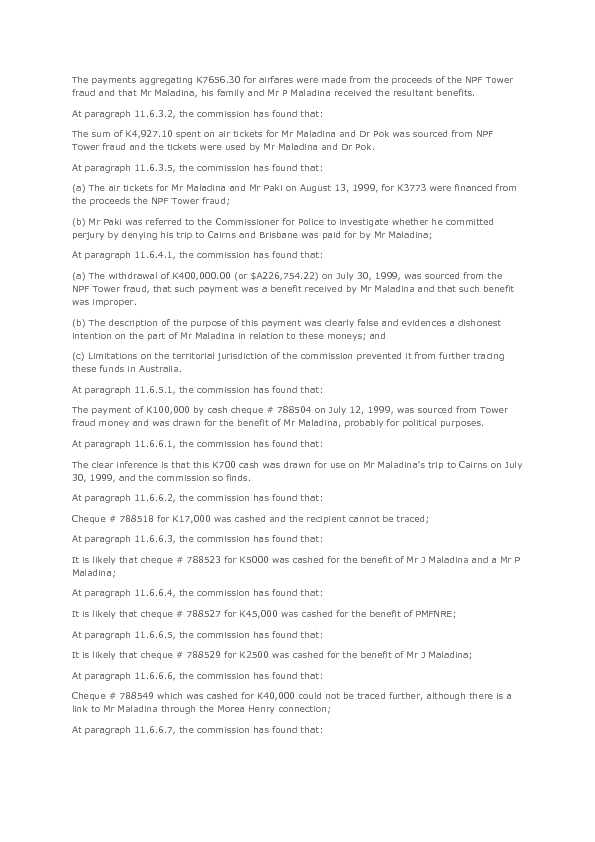

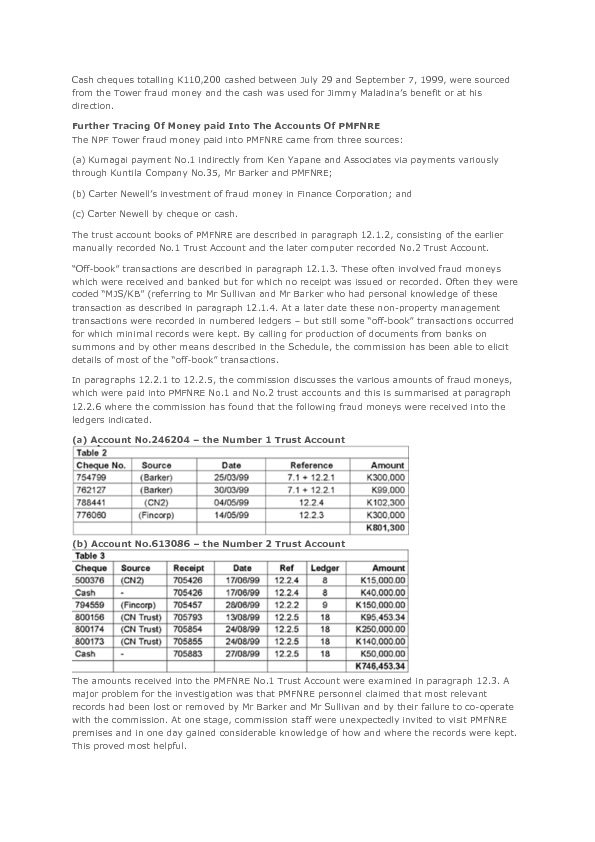

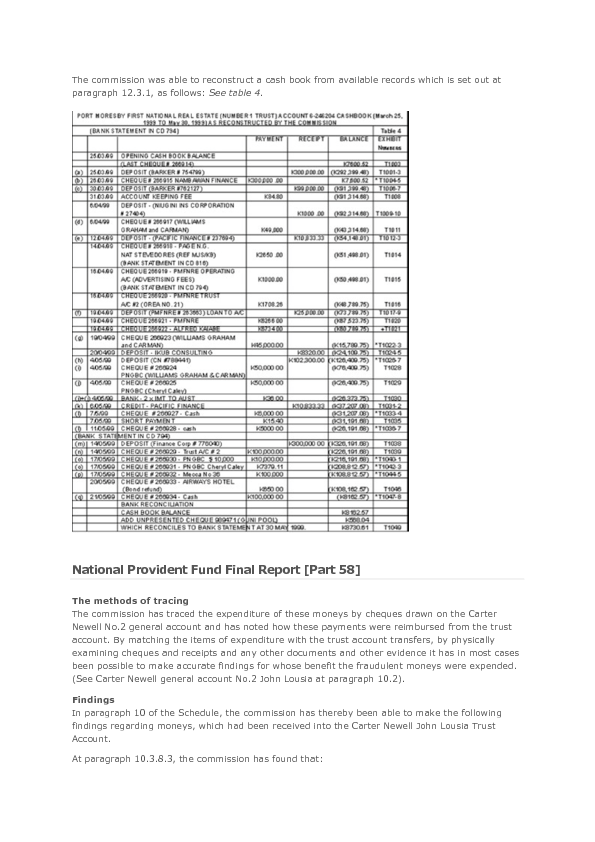

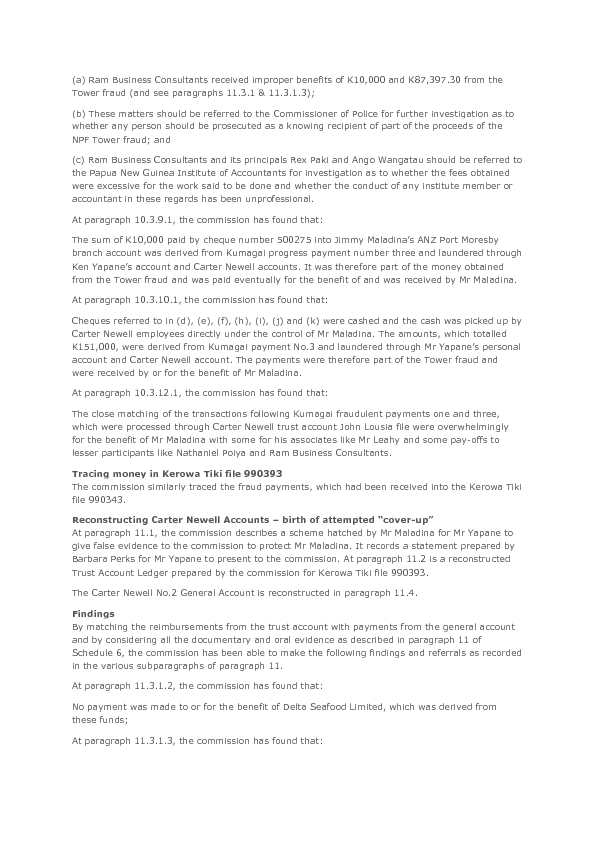

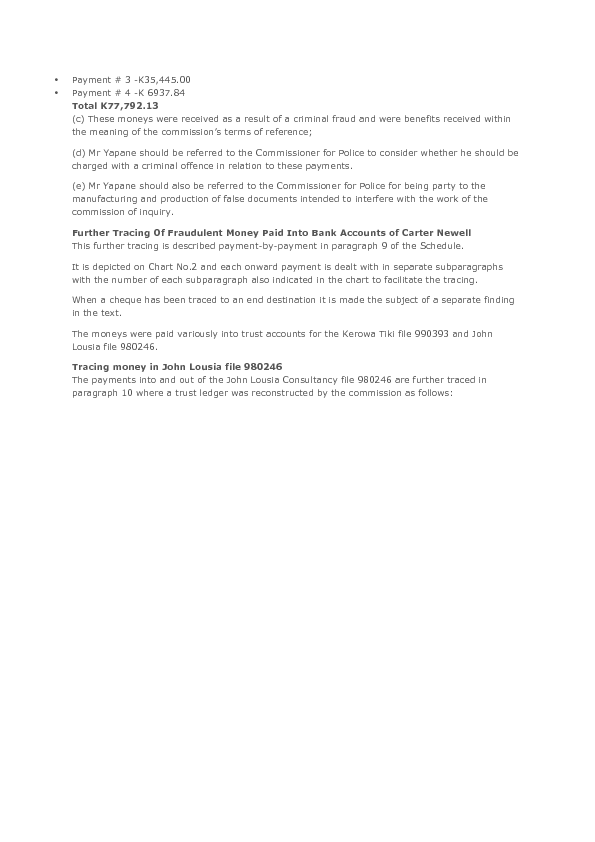

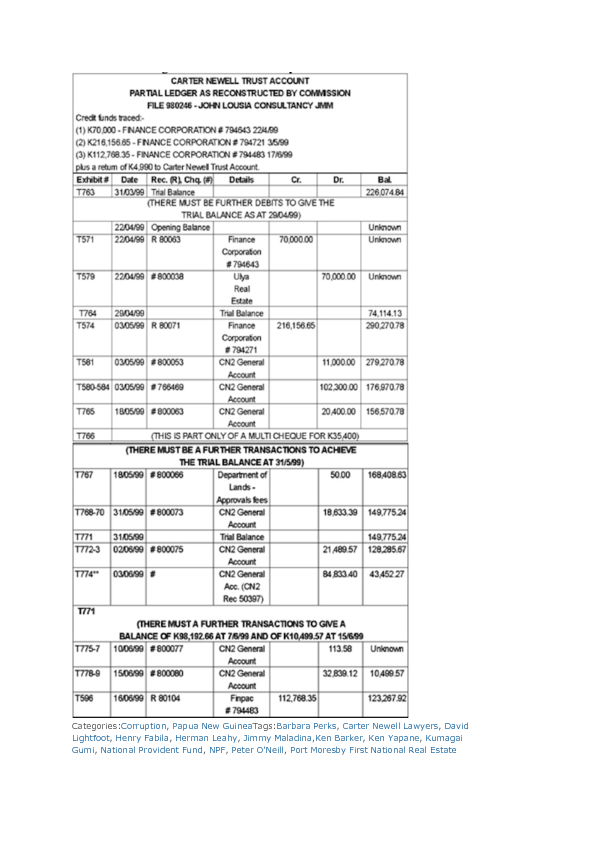

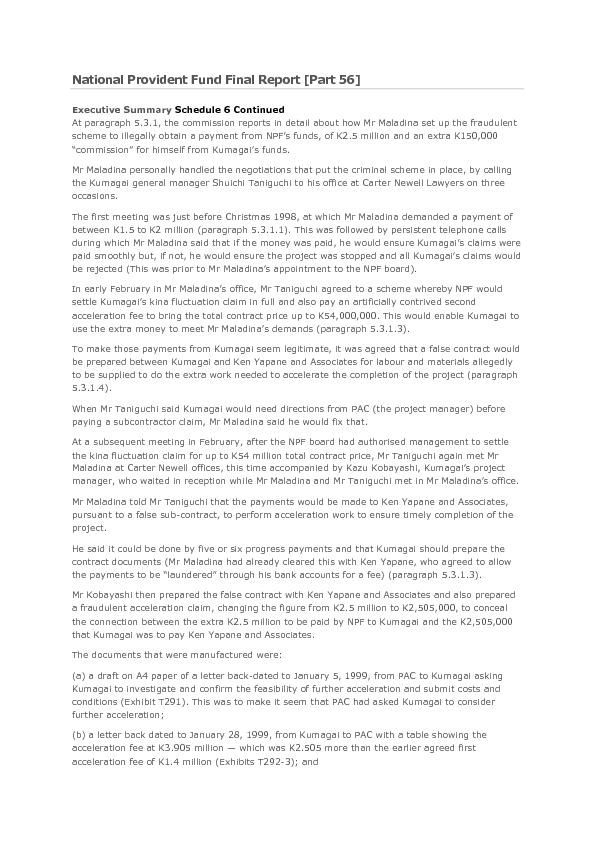

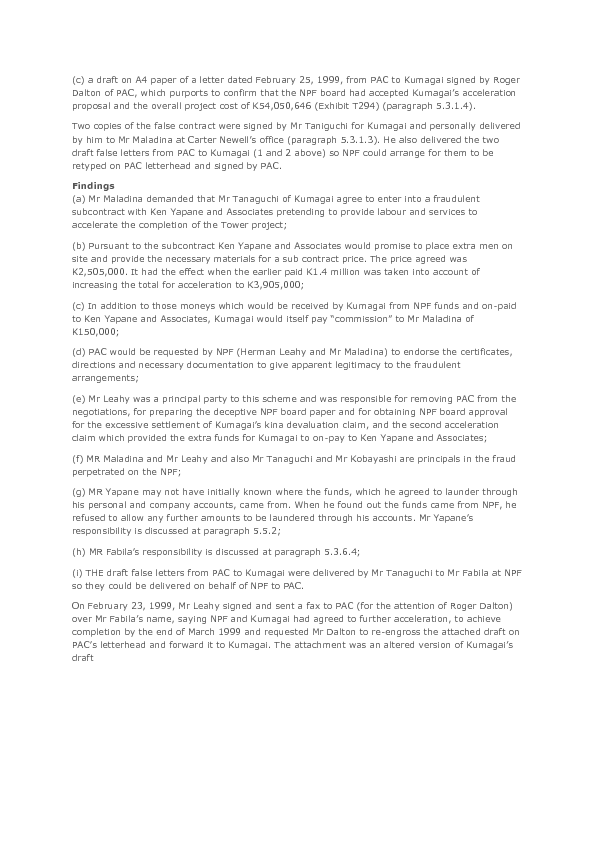

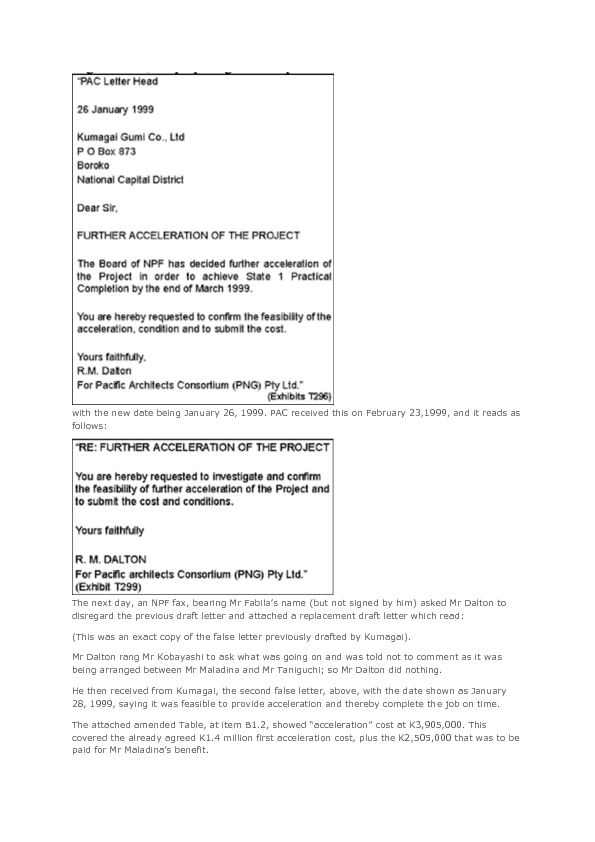

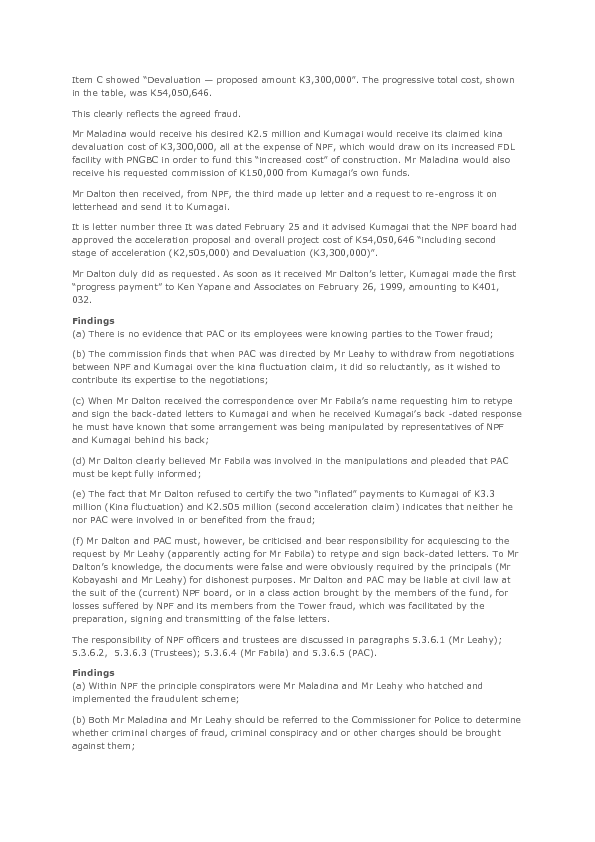

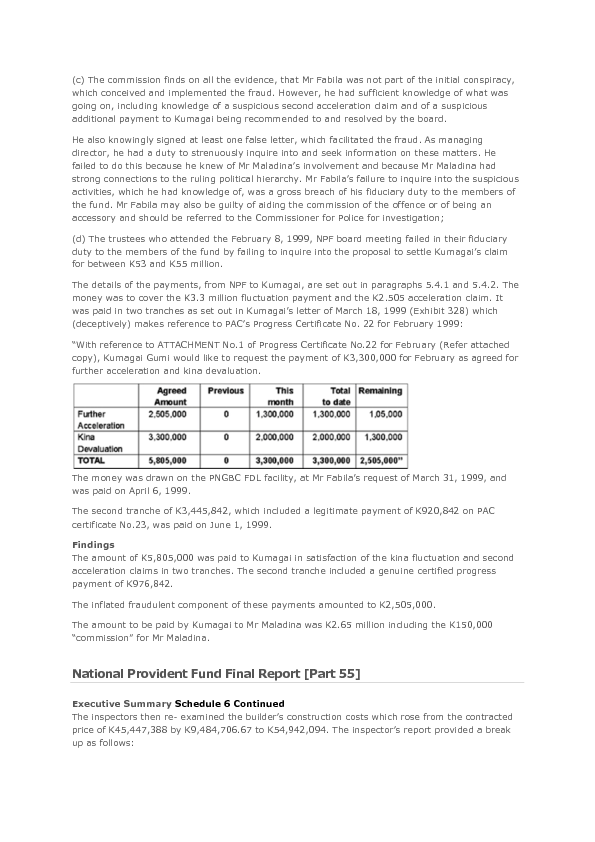

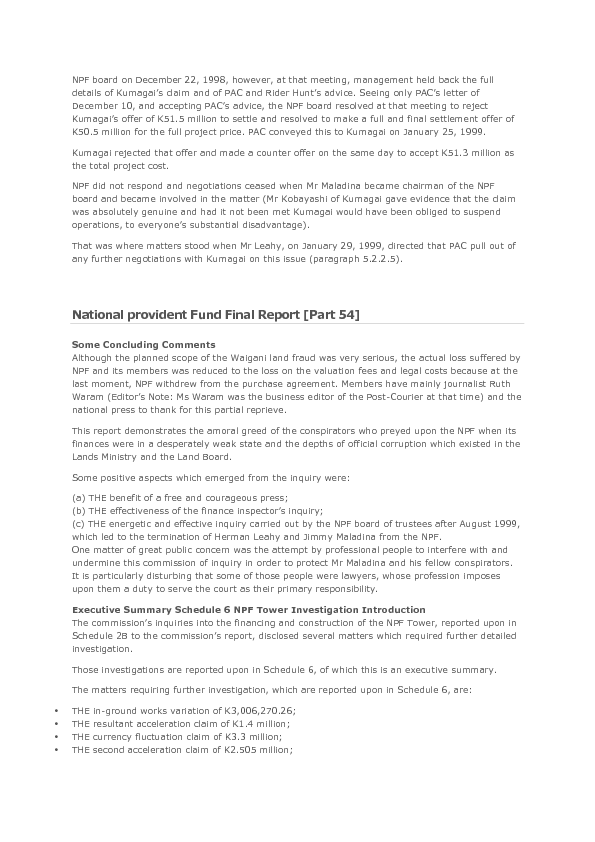

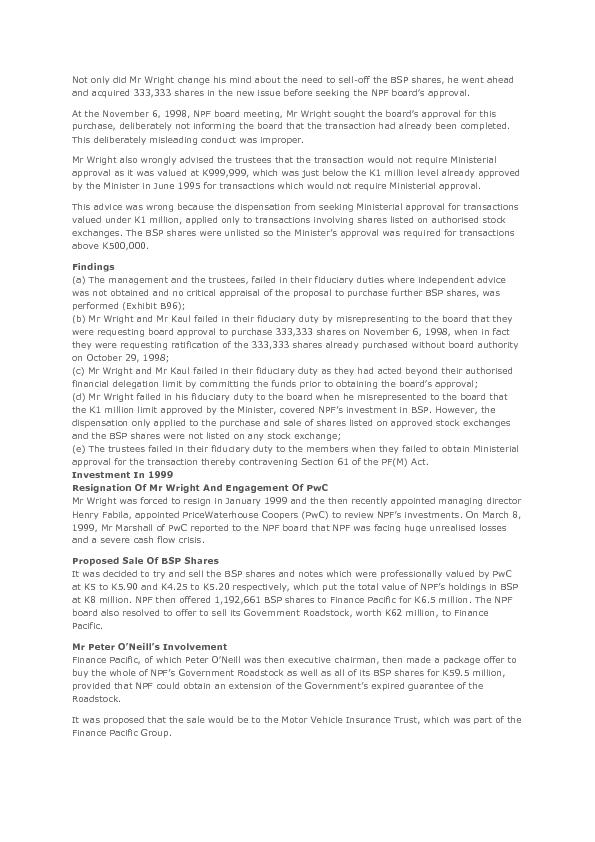

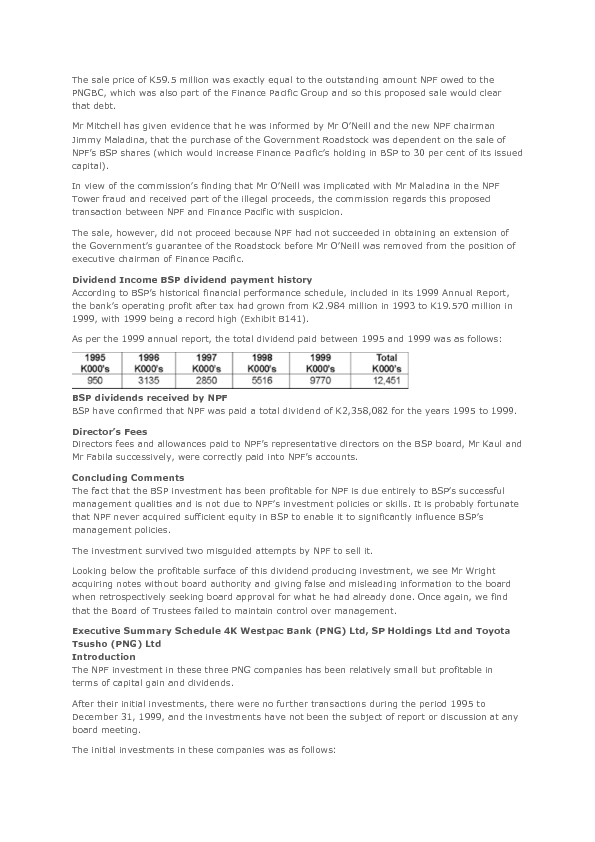

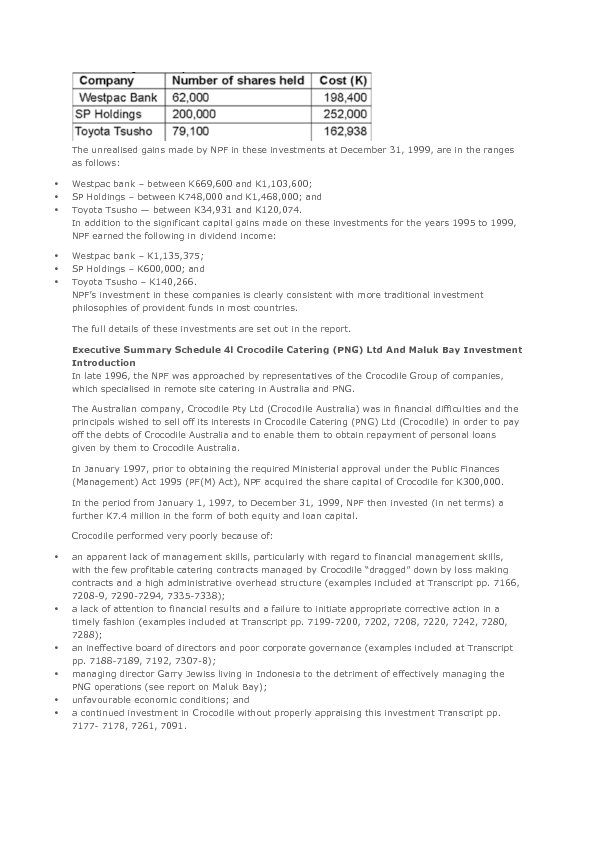

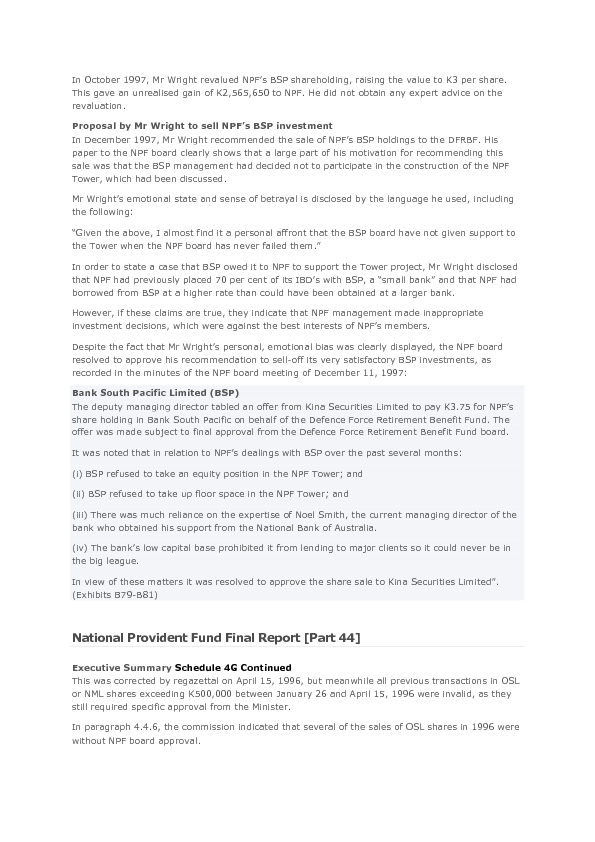

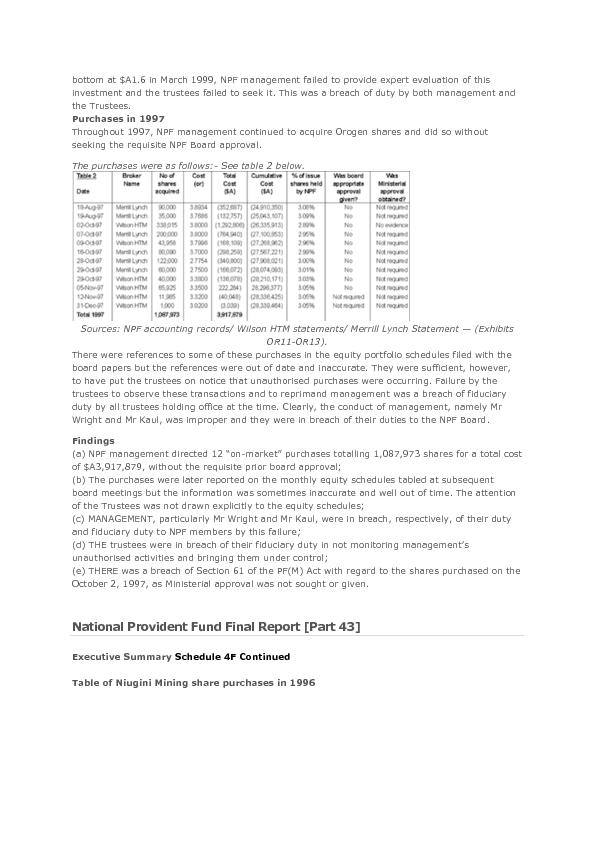

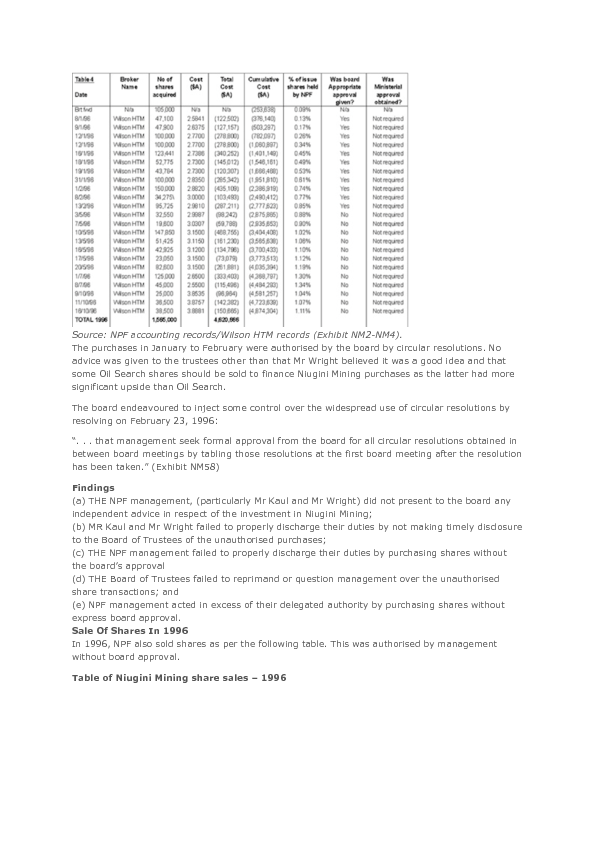

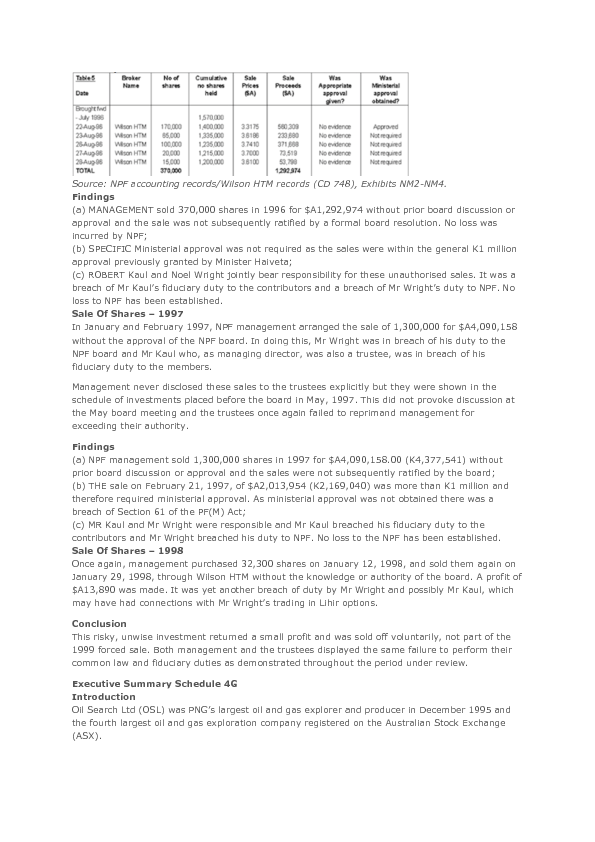

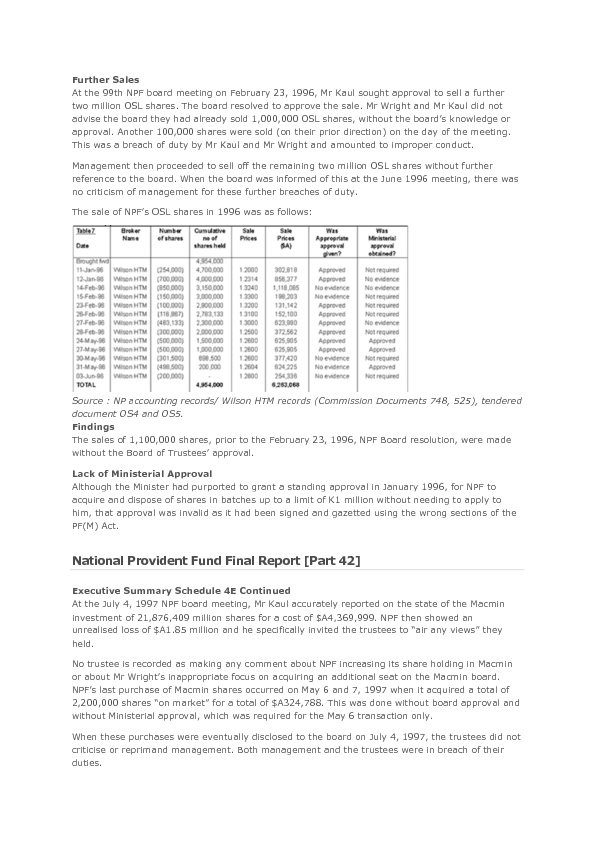

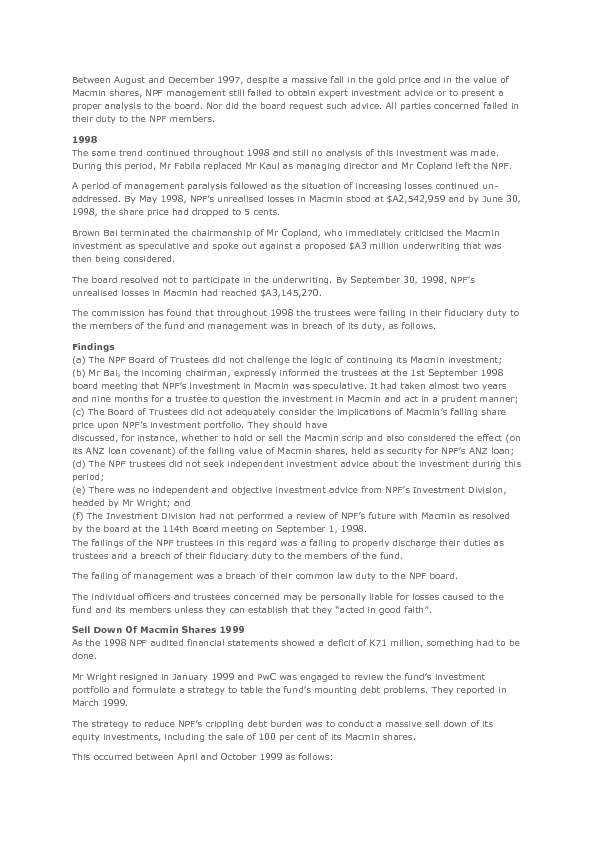

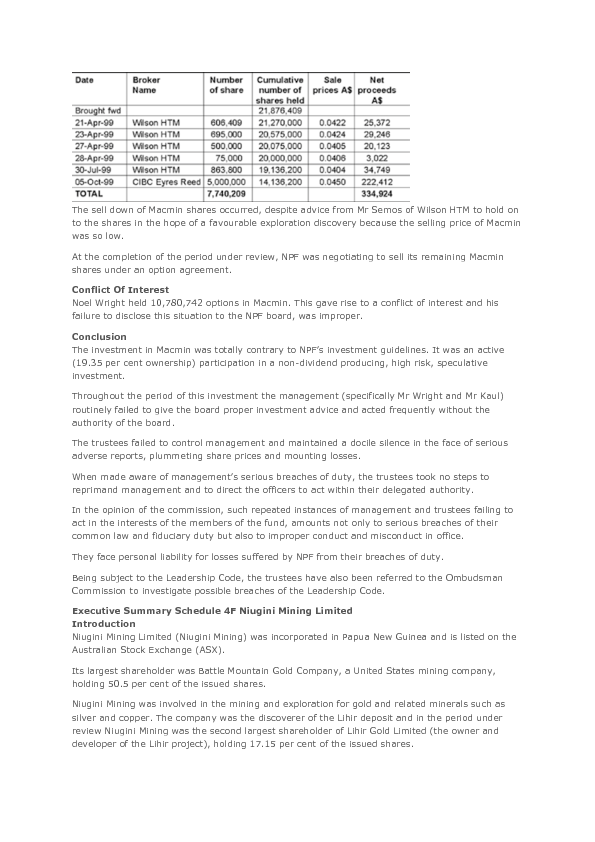

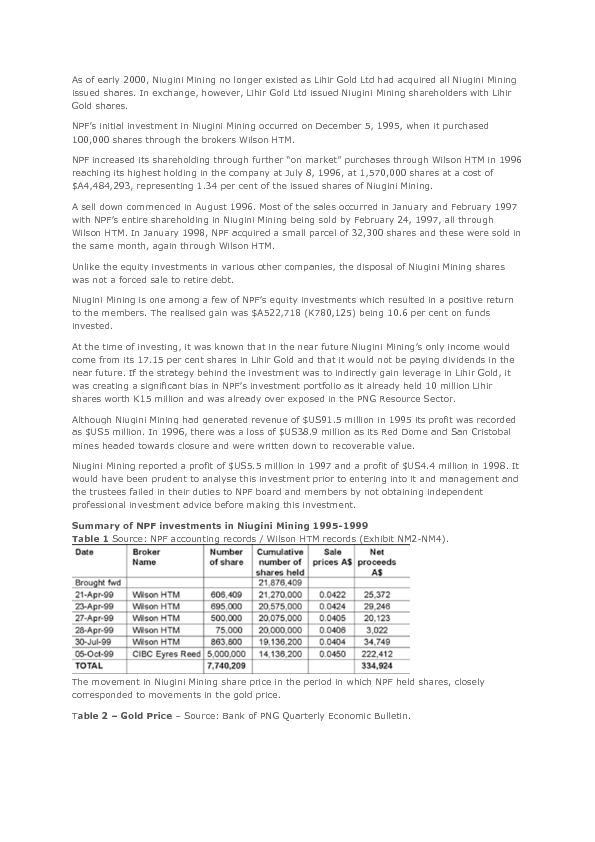

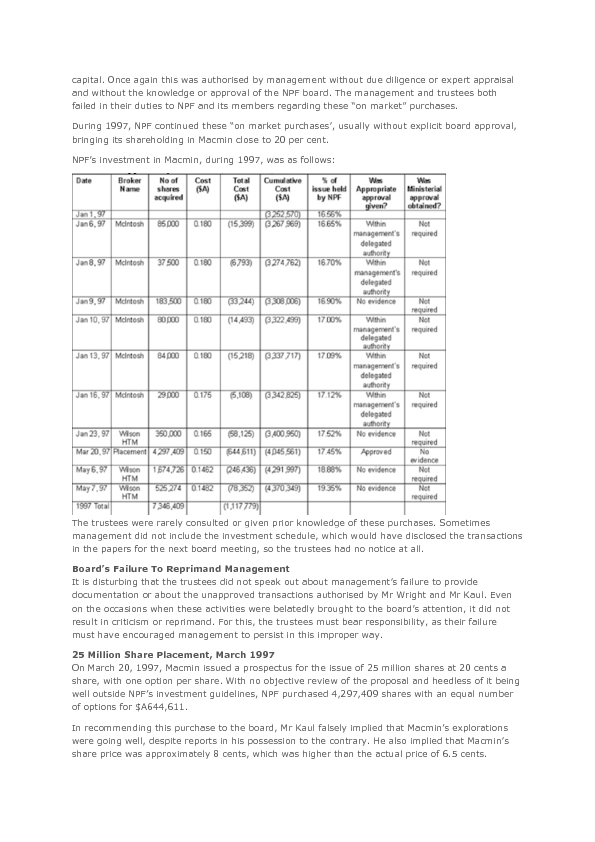

-