Leadership Tribunal verdict in the matter of Hon. Bryan Kramer MP

Mentions of people and company names in this document

We have not found any names of entities or people in this document that match names in our corporate records.

Document content

-

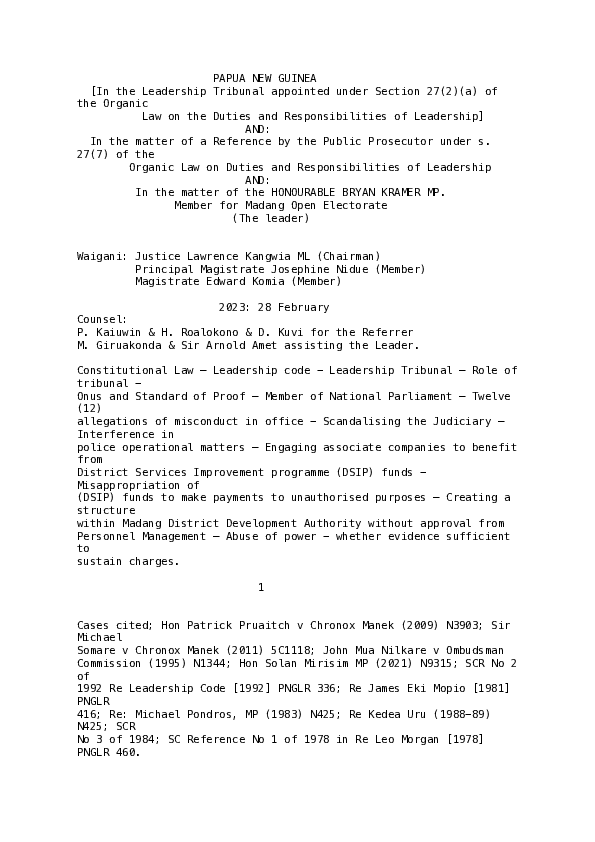

PAPUA NEW GUINEA

[In the Leadership Tribunal appointed under Section 27(2)(a) of

the Organic

Law on the Duties and Responsibilities of Leadership]

AND:

In the matter of a Reference by the Public Prosecutor under s.

27(7) of the

Organic Law on Duties and Responsibilities of Leadership

AND:

In the matter of the HONOURABLE BRYAN KRAMER MP.

Member for Madang Open Electorate

(The leader)Waigani: Justice Lawrence Kangwia ML (Chairman)

Principal Magistrate Josephine Nidue (Member)

Magistrate Edward Komia (Member)2023: 28 February

Counsel:

P. Kaiuwin & H. Roalokono & D. Kuvi for the Referrer

M. Giruakonda & Sir Arnold Amet assisting the Leader.Constitutional Law — Leadership code – Leadership Tribunal — Role of

tribunal –

Onus and Standard of Proof — Member of National Parliament — Twelve

(12)

allegations of misconduct in office – Scandalising the Judiciary —

Interference in

police operational matters — Engaging associate companies to benefit

from

District Services Improvement programme (DSIP) funds –

Misappropriation of

(DSIP) funds to make payments to unauthorised purposes — Creating a

structure

within Madang District Development Authority without approval from

Personnel Management — Abuse of power – whether evidence sufficient

to

sustain charges.1

Cases cited; Hon Patrick Pruaitch v Chronox Manek (2009) N3903; Sir

Michael

Somare v Chronox Manek (2011) 5C1118; John Mua Nilkare v Ombudsman

Commission (1995) N1344; Hon Solan Mirisim MP (2021) N9315; SCR No 2

of

1992 Re Leadership Code [1992] PNGLR 336; Re James Eki Mopio [1981]

PNGLR

416; Re: Michael Pondros, MP (1983) N425; Re Kedea Uru (1988-89)

N425; SCR

No 3 of 1984; SC Reference No 1 of 1978 in Re Leo Morgan [1978]

PNGLR 460. -

Page 2 of 61

-

Ex Parte Rowan CaHick and Joe Koroma (1985) PNGLR 67.

Legislations cited:

Constitution; s 27 (7) (e), 29 (1)

Organic Law on Duties and Responsibilities of Leadership; s13, 17

(d), 20 (4),

s27 (2) & (7) (e), s17 (d), s20 (4), 27 (1) & s28.

District Development Authority Act of 2014.

Public Finance Management Act; DSIP Guidelines, Finance instructions

National Procurement Act.INTRODUCTION

BY THE TRIBUNAL: This Tribunal was appointed pursuant to s27 (7) (e)

of the

Organic Law on Duties and Responsibilities of Leadership (Organic

Law) to

enquire into certain allegations of misconduct in office by the

Honourable Brian

Kramer MP, (the leader) within the meaning of s 27 of the

Constitution.The Ombudsman Commission originally referred 13 allegations of

misconduct in

office by the leader to the Public Prosecutor pursuant to s29 (1) of

the

Constitution and s 17 (d), s 20 (4) and s 27 (1) of the Organic Law

respectively.

On 30 September 2022 the Public Prosecutor pursuant to s 27 (2) of

the Organic

Law formally referred the Honourable Brian Kramer to the Leadership

Tribunal

by presenting 13 allegations. By operation of s 28 of the Organic

Law the leader

was suspended from official duties.On 14 October 2022 the Tribunal formally read the charges to the

leader. He

denied all allegations levelled against him. On 24 October 2022 the

Public

Prosecutor presented the statement of reasons accompanying the

charges

through the Chief Ombudsman Commissioner.2

In the process of the hearing allegation 10 was discontinued for

duplicity and

the trial proceeded with 12 allegations. During the trial thirteen

(13) witnesses

were called by the referrer while the leader called three (3)

witnesses.

Each witness was subjected to examination, cross examination, and

re-

examination. At the conclusion of the trail proper the hearing was -

Page 3 of 61

-

adjourned

to 20 February 2023 for parties to prepare submissions on verdict.CONSTITUTIONAL ISSUE

On the date fixed for submissions, the leader proposed that the

Tribunal first

consider a preliminary constitutional issue seeking to dismiss the

entire

proceeding. It was intimated that the threshold issue related to the

failure by

the Ombudsman Commission to afford him the right to be heard when it

refused to provide him the relevant evidence sought to be relied on.

He relied

on the case of Hon Patrick Pruaitch v Chronox Manek (2009) N3903 and

Sir

Michael Somare v Chronox Manek (2011) SC1118 as conferring authority

on

the Tribunal to consider any question of interpretation and

application of a

Constitutional nature that may arise concerning the investigation by

the

Ombudsman Commission.

In view of the necessity to accord the right to be heard at any

stage of the

proceeding the tribunal granted leave for the leader to incorporate

the issue

in its submissions on verdict to be determined separately. The

effect of the

grant of leave was that if the Preliminary issue was in favour of

the leader the

proceeding could stand dismissed. If the preliminary issue was

denied the

decision on verdict would be delivered.

This is the decision from that preliminary issue. The leader’s

submission was

that by the refusal to provide him the evidence sought to be relied

on by the

Ombudsman Commission he was denied a fair and reasonable opportunity

to

respond to the allegations as intended by s 20 (3) of the Organic

Law on Duties

and Responsibilities of Leadership. If he had been provided the

relevant

evidence constituted of 20 volumes containing 8,488 pages of the

alleged

breaches, he would have offered an explanation or clarification that

would

have dispelled the allegations leading to a no prima facie case.

3Without exercising due diligence and giving him the opportunity to

be heard -

Page 4 of 61

-

the Ombudsman Commission made a deliberate decision to refer him to

the

Public Prosecutor which was a breach of his Constitutional right,

and the

Tribunal should dismiss all charges.

He relied on the cases of John Mua Nilkare v Ombudsman Commission

(1995)

N1344 and the findings by the Tribunal in the Hon Solon Mirisim MP

(2021)

N9315 as authority supporting his proposition.

The referrer while contending that the leader was accorded the right

to be

heard by the Ombudsman Commission submitted that the issue raised

was

belated. The leader had the opportunity to raise it as a preliminary

issue when

the Tribunal hearing commenced and not after evidence had been

called and

completed. On the case of Solan Mirisim cited by the leader it was

intimated

that the circumstances of that case were different to the present

application

and not relevant.

We agree with the law and case authority on the right to be heard. A

right to

be heard generally remains with a person to the grave so to speak.

The right

to be heard by a leader facing misconduct allegations must be

accorded a fair

hearing and given the opportunity to respond or challenge what is

alleged.

However, we have reservations on the view that a leader should be

called in

for an interview. An allegation by its very nature is an allegation

yet to be

proved and a leader should not be subjected to an interview akin to

a felon in

a criminal case at a police station. There is a basic presumption

that Leaders

are expected to know and do what is right and do it properly for

without the

necessary attributes, they should not hold leadership positions in

the first

place.

In the present preliminary application by the leader, our view is

consistent

with the position of the referrer. The issue raised is far belated.

It is in essence

asking the tribunal to disband without considering the evidence

already

before it. There was nothing preventing the leader from raising the

issue as a

preliminary or competency issue when the Tribunal first commenced

the -

Page 5 of 61

-

hearing. The only preliminary issue that parties were invited to

address at the

commencement of hearing was the composition of the Tribunal members.4

Even then, because the leader’s application involved Constitutional

issues the

proper remedy in our view lay in a judicial review as was in the

Patrick Pruaitch

case that the leader referred to.

From the evidence before us the leader was not completely deprived

of the

right to be heard. The unchallenged evidence is that on 3rd

December 2021

the Ombudsman Commission served the leader the right to be heard.

Annexed to the letter was the statement of reasons on the 13

allegations in a

291 paged document sought to be relied on. The leader on 4th

December 2021

by letter sought an extension of 21 days to respond and further

requested

copies of the evidence sought to be relied on. On 20 December 2021

the

Ombudsman Commission granted an additional 21 days and refused to

provide any evidentiary documents.

Because the leader was not provided the evidentiary documents, the

leader

deemed it unfair and saw no utility in responding to the right to be

heard.

When no response was received after the extension period lapsed the

Ombudsman Commission on 14 February 2022 by letter notified the

leader

that it would refer the leader to the Public Prosecutor for not

responding and

made a deliberate finding of prima facie guilty of misconduct in

office. On 15

March 2022 the Ombudsman Commission referred the leader to the

Public

Prosecutor. The referral to the Public Prosecutor included the 20

volumes of

evidence that was refused to be served on the leader.

This case was not a situation like the case of Solan Mirisim. In

that case the

right to be heard was given some years after the allegations arose

and the

leaders was referred to the public prosecutor 6 years thereafter.

The dismissal

by the Tribunal was based on denial of a fair hearing.

In the present case the leader was not denied a fair hearing. He was

accorded

the opportunity to exercise his right to be heard by the Ombudsman

Commission soon after it completed its investigation. The refusal to -

Page 6 of 61

-

provide

the documentary evidence did not extinguish his right to be heard.

He was still

possessed of the right. The assertion that had he been given the

documentary

evidence he would have provided a proper and better explanation

which

would have found a basis for a no prima facie case is in our view

farfetched.

He did not do that when he was accorded the right to be heard in the

Tribunal.

5He pleaded not guilty to the allegations when put to him. When he

pleaded

not guilty, he was deemed to have accepted what transpired thereby

setting

in motion the hearing proper to proceed.

The trial proper proceeded therefrom without any challenge as to its

propriety, competency, or lack of jurisdiction. Even then the leader

still is

possessed of the right to be heard if he is not satisfied by any

determination

the Tribunal makes.

For those reasons we decline to grant the orders sought by the

leader.

We now deliver the unanimous decision of the Tribunal from the

hearing proper.DECISION

We start with the notion reposited in SCR No 2 of 1992 Re Leadership

Code

[1992] PNGLR 336 that the thrust of the Leadership Code is to

preserve the

people of this country from misconduct by its leaders. That private

interest does

not conflict with public responsibility as a leader. Leaders subject

to the

Leadership Code are those classified under s 26 of the Constitution.

Leadership

can be either earned or given. Either way the leader is accountable

for any

misconduct while in office.To safely hold a leader guilty of misconduct in office, factual

allegations must be

proved before a determination is made as to whether the proven facts

constituted a breach of the duties enumerated under s 27 of the

Constitution.In a Tribunal there is no legal onus to prove but the basic

principle of law is that -

Page 7 of 61

-

any person who alleges an illegal act, practice or conduct bears the

burden of

proving what he or she alleges, and Leadership Tribunals enjoy no

exception to

the grounded principle, the minimum being the practical onus to

satisfy the

principles of natural justice at every stage of the proceeding.By the very nature of the alleged misconduct in office created by

the

Constitution and implemented through the Organic Law on the Duties

and

Responsibilities of Leadership, it will require a high standard of

proof.6

Case law embrace the view that standard of proof in a leadership

Tribunal must

be high and nearer to the criminal standard of proof beyond

reasonable doubt.

This requirement is well founded in this jurisdiction as in the

case of Re James

Eki Mopio [1981] PNGLR 416 where the Court illuminated the

requirement this

way.

“There is no absolute degree of standard of proof to be applied by

the Leadership

Tribunal. The Tribunal must be reasonably satisfied of the truth of

the

allegations, and it must.give full weight to the gravity of the

misconduct in office

by a person subject to the leadership code to the adverse

consequences which

may follow and to the duty to act judicially and in compliance of

the principle of

natural justice. Such satisfaction in matters so grave can never be

achieved on a

mere balance of probabilities”. (See also Re: Michael Pondros, MP

(1983) N425;

Re Kedea Uru (1988-89) N425)By the requirement for a high standard of proof the Tribunal is

restricted to the

allegations as pleaded in the referral by the Public Prosecutor.

Unless an

allegation is withdrawn by the referrer the tribunal must make a

finding on each

allegation.In the present case there is no dispute that between 27 July 2017

and 27 July

2022 the Hon Bryan Kramer MP was, a leader by virtue of s 26 (1) -

Page 8 of 61

-

(c) & (d) of the

Constitution in his capacity as member for Madang Open. By virtue

of that office,

he became the Chairman of the Madang District Development Authority

(Authority) pursuant to s 12 (1) (a) of the District Development

Authority Act

(the Act). He was returned to the same leadership post in the 2022

National

Elections. He is therefore subject to the responsibilities of

leadership prescribed

under s 27 of the Constitution.From the 12 categories of allegations referred to the tribunal 07

of them were

alleged to have breached responsibilities of office under s 27 (5).

(b) of the

Constitution while 05 related to misappropriation of funds of Papua

New Guinea

under s 13 of the Organic Law. it was the duty of the Tribunal to

enquire into

and determine, whether the 12 categories of allegations breached

obligations

imposed by s 27 (5) (b) of the Constitution relating to

responsibilities of office7

and s 13 of the Organic Law which relates to misappropriation of

funds of Papua

New Guinea to constitute misconduct in office.Since s 27 (5) (b) of the Constitution subsumes all the preceding

subsections, we

reproduce the entire provision along with s 13 of the Organic Law.The provisions state as follows;

27. Responsibilities of office.

(1) A person to whom this Division applies has a duty to conduct

himself in

such a way, both in his public or official life and his private

life, and in his

associations with other persons, as not—

(a) to place himself in a position in which he has or could have a

conflict of

interests or might be compromised when discharging his public or

official duties;

or

(b) to demean his office or position; or

(c) to allow his public or official integrity, or his personal

integrity, to be called

into question; or

(d) to endanger or diminish respect for and confidence in the

integrity of -

Page 9 of 61

-

government in Papua New Guinea.

(2) In particular, a person to whom this Division applies shall not

use his office

for personal gain or enter into any transaction or engage in any

enterprise or

activity that might be expected to give rise to doubt in the public

mind as to

whether he is carrying out or has carried out the duty imposed by

Subsection (1).

(3) It is the further duty of a person to whom this Division applies

—

(a) to ensure, as far as is within his lawful power, that his spouse

and children

and any other persons for whom he is responsible (whether morally,

legally or by

usage), including nominees, trustees, and agents, do not conduct

themselves in

a way that might be expected to give rise to doubt in the public

mind as to his

complying with his duties under this section; and

(b) if necessary, to publicly disassociate himself from any activity

or enterprise

of any of his associates, or of a person referred to in paragraph

(a), that might

be expected to give rise to such a doubt.

(4) The Ombudsman Commission or other authority prescribed for the

purpose under Section 28 (further provisions) may, subject to this

Division and to

any Organic Law made for the purposes of this Division, give

directions, either

generally or in a particular case, to ensure the attainment of the

objects of this

section.

(5) A person to whom this Division applies who-8

(a) is convicted of an offence in respect of his office or position

or in relation

to the performance of his functions or duties; or

(b) fails to comply with a direction under Subsection (4) or

otherwise fails to

carry out the obligations imposed by Subsections (1), (2) and (3),

is guilty of

misconduct in office.13. Misappropriation of funds of Papua New Guinea

A person to whom this law applies who

(a) Intentionally applies any money forming part of any fund under

the

control of Papua New Guinea to any purpose to which it cannot be

lawfully -

Page 10 of 61

-

applied; or

(b) Intentionally agrees to any such application of any such

monies.

is guilty of misconduct in office.The combined effect of those provisions is to deter abuse of power

and influence

for personal benefit or gain as enunciated in SC Reference No 1 of

1978 in Re Leo

Morgan [1978] PNGLR 460. The extent of responsibilities and the type

of

conduct expected of a leader by s 27 in his public and personal life

is high, wide,

and varied. There is no precise definition of conduct. We adopt and

endorse the

opinion of the Tribunal in the Matter of Solan Mirisim MP (2021)

N9315 which

said, “In our opinion s. 27 is an all-encompassing law that covers

all forms of

leadership breaches constituting misconduct in office by leaders”.We now deal with the categories of allegations this way. Allegations

1, 2, and 4

will be considered together as they overlap and relate to the 03

articles posted

on the leader’s Facebook account. All the 3 allegations deem the

leader as guilty

of misconduct in office under s 27 (5) (b) of the Constitution.Allegation 1. Scandalising the Judiciary by posting articles on his

Facebook

account and insinuating a conflict of interest by the Hon. Sir Gibbs

Salika, Chief

Justice of Papua New Guinea.Under this category the referrer alleged that the leader failed to

carry out

obligations imposed by s 27 (1) of the Constitution by publishing

articles

insinuating a conflict of interest when he published these words; “A

relevant

point to note is that the Chief Justice was only recently appointed

by O’Neill late

last year.9

In submissions the position of the referrer was that the leader

being a person of

intelligence while knowing that the Chief Justice was appointed by

the National

Executive Council, published an inaccurate fact that the Chief -

Page 11 of 61

-

Justice was

recently appointed by O’Neill. That his actions amounted to

ridiculing and

mocking the Chief Justice and disrespect for the judiciary which is

dangerous to

democracy.By writing and publishing those words it brought the Court or Judge

into

disrepute; lower the authority of the Court; lower the authority of

the Chief

Justice, interfere with due course of justice; interfere with lawful

process of the

Court; and undermine public confidence in the administration of

justice.By doing so he demeaned his office, allowed his official and

personal integrity to

be called into question and endanger or diminish respect for and

confidence in

the integrity of government and therefore he was guilty of

misconduct in office

under s 27 (5) (b) of the Constitution.The leader while acknowledging that the statement was inaccurate

contended

that when properly understood it merely stated a constitutional fact

that the

Chief Justice was recently appointed by Prime Minister O’Neill’s

government

and cannot be said to be scandalous in any way whatsoever.That by merely publishing this constitutional fact he did not demean

his office

or position nor allow his personal integrity, or his personal

integrity to be called

into question within the meaning of s 27 (1) (b) of the

Constitution. The

publication was not scurrilous, abusive or cast any imputations

against the

judiciary or unduly spoken against a member of the judiciary or the

judiciary

generally.The main contention was that the charge cannot be sustained because

scandalising is a form of Contempt of Court and a serious criminal

offence under

Common Law where the standard of proof was high and the requirement

to

prove the elements of the charge was not met rendering the

allegation against

him as speculations and assumptions.10

-

Page 12 of 61

-

Therefore, the charge should be dismissed. He referred to the SCR

No 3 of 1984;

Ex Parte Rowan Callick and Joe Koroma (1985) PNGLR 67 which cited

various

overseas cases as authority for his assertion that scandalising is

a form of

contempt.Allegation 2. Scandalising the Judiciary by posting articles on his

Facebook

account accusing Hon Peter O’Neill and his lawyers of filing a fake

Warrant of

Arrest to deceive and mislead the Court in the matter OS (JR) 720 of

2019.Under this category the allegation was that the leader as Minister

for Police

scandalised the Court by posting on his Face Book account the

following words.“What was not anticipated was that O’Neill and his lawyers would

solicit

assistance from the Chief Justice and desperate enough to submit

fabricated

documents to mislead the Court that the Warrant was defective as a

means to

obtain a stay order”.The submission by the referrer was that the publication was a

malicious

accusation against O’Neill and his lawyers and intended for the

public to draw

the conclusion that since O’Neill appointed the Chief Justice the

request to the

Chief Justice was for a return favour. That he had the intention to

scandalise the

Chief Justice and or the Judiciary when he published the following

words on his

Facebook account;“In response the Chief Justice hand-wrote on the same letter

directing the judge

to attend to the matter for a temporary stay until 21st October

2019; Miviri

please attend to this matter for a temporary stay until 21/10/19;

following the

directions issued by the CJ Miviri J vacated his earlier directions

and agreed to

hear O’Neill’s lawyers application at 3pm that afternoon; After

hearing the

application consistent with Os directions the judge granted an

interim stay, -

Page 13 of 61

-

restraining police from arresting and executing the warrant of

arrest against

0,Neill until Monday 21st October 2019; A relevant matter to not is

that the Chief

Justice was only recently appointed by O’Neill last years.”11

That in the totality of the circumstances the articles the leader

posted on

Facebook had the effect of scandalising the judiciary as they were

calculated to

bring the Court or Judge into disrepute and lower the authority of

the Chief

Justice and the Court and undermine and endanger public confidence

in the

judiciary. By doing so the leader demeaned his office and positions,

allowed his

official integrity into question and endangered and diminished

respect for and

confidence in the integrity of government thereby being guilty of

misconduct in

office under s 27 (5) (b) of the Constitution.The leader while adopting his contentions under allegation 1

intimated that the

publication complained of were directed at the unethical and

inappropriate

conduct of Mr O’Neill’s lawyers and not against the Chief Justice.

They did not

scandalise the Court or bring the Court into disrepute, lower the

authority of the

chief Justice or interfere with the due course of justice. In like

manner the

publication did not demean his office and position or allow his

official or

personal integrity into question therefore he was not guilty of

misconduct in

office under s 27 (5) (b) of the Constitution.Category 4. Publicizing the complaint lodged against him by Hon Sir

Gibbs Salika

the Chief Justice of Papua New Guinea and posting it on the Facebook

account.Under this category the referrer alleged that the leader failed to

carry out

obligations imposed by s 27 (1) of the Constitution when he

published the letter

of complaint by the Chief Justice to the Police Commissioner which

was

calculated to bring the integrity of the Chief Justice into -

Page 14 of 61

-

disrepute, interfere with

due course of justice, and undermine public confidence in the

administration of

justice thereby being guilty of misconduct in office under s 27 (5)

(b) of the

Constitution.The leader’s contention was that he did not use his office or

position to obtain

from the Commissioner of Police the letter by the Chief Justice nor

publishes it.

The letter had been publicized by one Nathan Liwago on WhatsApp

platform. It

was the leader’s assertion that even if he had published the letter,

it would not

amount to misconduct in office by any measure.12

It was his further contention that the process from criminal

complaints to

sentence were supposed to be transparent and not confidential.

Since the

document consisted of a criminal complaint against him personally

and as the

most affected person, he had to publish it to let his electors in

Madang know

that a criminal complaint had been laid against him for transparency

purposes.

Therefore, the allegation was baseless, and should be dismissed.The approach we take is that the allegations will be considered in

totality.The allegations shall be viewed objectively according to the

standards and

reactions of the reasonable person. It is irrelevant whether the

Common Law

recognises scandalising the judiciary as a form of contempt as

intimated by the

leader. The Common Law recognition relates to publications

concerning ongoing

proceedings because any publication regarding an ongoing proceeding

is

prohibited. The case that was the subject of the publications in

this proceeding

was a dead and done case.Our findings under categories 1, 2 and 4 are these. The evidence

presented

under the three categories of allegations show elaborate articles

produced by

the leader on his Facebook account in three parts on separate dates -

Page 15 of 61

-

between

2nd and 10 November 2019.The articles had its genesis from a criminal complaint laid by the

leader against

Peter O’Neill on 7 October 2019 for abuse of office for directing

the payment of

more than K300, 000 from the National Gaming Control Board which

eventually

helped his political nemesis Nixon Duban win the Madang Open

Electorate

under the auspices of upgrading Yagaum Lutheran Rural Hospital. Out

of that

transaction the Court of Disputed Returns found Duban guilty of

bribery and

undue influence and voided his election as member.Following the leader’s complaint, a Warrant of Arrest was necessary

to bring

O’Neill for questioning by police. Police obtained from the Waigani

District Court

a Warrant of Arrest against O’Neill.13

On 16 October 2019, before police could execute the Warrant of

Arrest, O’Neill

through Nivage Lawyers sought an urgent application in the National

Court for

orders to stay the Warrant of Arrest from being executed. The reason

for the

application by O’Neill was to seek Judicial Review of the decision

to issue the

Warrant of Arrest which was couched as constituting patent defects.

The

application ended up with Hon Justice Miviri twice.On both occasions, Hon Justice Miviri fixed 21 October 2019 as the

date for

hearing the application inter-parte. Not satisfied with Hon Justice

Miviri’s

decision and fearing imminent arrest, Peter O’Neill’s lawyer wrote

to the

Associate to the Chief Justice Togi Maniawa seeking an urgent

interim stay.

That letter was forwarded to the Chief Justice. Upon receipt of that

letter the

Hon Chief Justice by notation on the same letter wrote the following

words:

“Miviri J. Please attend to this matter for a temporary stay until

21/10/19”. -

Page 16 of 61

-

Following that notation Hon Justice Miviri heard the application and

granted

orders restraining police from executing the Warrant of Arrest

pending

determination of the substantive proceedings. Peter O’Neill was not

arrested.

On the return date police withdrew the warrant of arrest and O’Neill

was not

charged.After those occurrences, the leader on 2r November 2019 commenced

posting

on his Facebook account, articles containing events and comments

leading to

and surrounding the stay order. The articles posted in three parts

were entitled

“O’Neill flees country as National Court dismisses his case

preventing arrest”.The articles alleged to be scandalous started like this.

“Following the directions issued by the Chief Justice, Judge Miviri

vacated his

earlier directions and agreed to hear O’Neill’s lawyers’ application

at 3 pm that

afternoon. After hearing the application, consistent with CJ’s

directions the Judge

granted an interim stay, restraining police from arresting and

executing the

Warrant of Arrest against O’Neill until Monday 21st October 2019.The words alleged to be scandalous are these;

14“A relevant matter to note is that the Chief Justice was only

recently appointed

by O’Neill late last year”. And later;

“What was not anticipated was that O’Neill and his lawyers would

solicit

assistance from the Chief Justice and desperate enough to submit

fabricated

documents to mislead the Court that the Warrant was defective as a

means to

obtain a stay order”.Being aggrieved by the articles the Chief Justice wrote a letter to

the acting

Commissioner of Police, David Manning to charge the leader under the

Summary Offences Act and possibly the Cybercrimes Act. He also wrote

to the

Ombudsman Commission. The leader upon receipt of a copy of the

letter posted

the entire letter on his Facebook account. Thereafter numerous -

Page 17 of 61

-

comments and

responses from the public were published. The Ombudsman Commission

investigated and referred the leader to the Public Prosecutor under

the three

categories of allegations.We commence our finding with the view that in a democracy like ours,

freedom

of speech generally is a noble calling. The Constitution under s 46

recognises

that proposition as freedom of expression. However, such freedom

must be

exercised with caution and restraint to avoid adverse consequences.

Our findings of the primary facts from the Facebook articles are

these. The

heading to the Facebook articles stated, “O’Neill flees country as

National Court

dismisses his case preventing arrest”. The leader’s assertion that

the National

Court dismissed O’Neill’s case is far from the truth. There is no

evidence that the

National Court dismissed O’Neill’s case.

There is also no evidence that O’Neill was charged with any offence

that was

dismissed. What is in evidence is that the Warrant of Arrest was set

aside by

court order. It is a misstatement and a distortion of facts by the

leader to assert

in the Facebook articles that O’Neill’s case was dismissed.

Secondly, from the information before us there is no evidence that

O’Neill and

his lawyer solicited any assistance from the Chief Justice. This

position was

enhanced in evidence during cross examination of George Lau the

Lawyer acting

for O’Neill, that communication with the Chief Justice was a “no go”

for a lawyer.15

The only evidence on record is that the lawyer for O’Neill wrote to

the associate

to Chief Justice requesting an urgent stay. That mode of

communication is the

norm for Court record purposes as the National Court is a Court of

record.

Thirdly, there is no evidence of a collusion by the Chief Justice

with Greg

Shepard’s Law firm where the Chief Justice’s daughter worked. The

undisputed

evidence is that Nivage Lawyers appeared in court after briefing out

from Greg

Shepard’s Law Firm relating to the application for a stay order -

Page 18 of 61

-

which is a normal

practice among lawyers.

Finally, there is no evidence of a defective or fake Warrant of

Arrest as alleged.

There is also no evidence that O’Neill and his lawyer used a fake

Warrant of

Arrest to obtain the stay order.

However, there is evidence of a Warrant of Arrest that was tampered

with. The

oral evidence by Senior Constable Kila Tali who applied for the

Warrant of Arrest

told the Tribunal that he tampered with the copy given to him by

ticking it which

was not ticked when he obtained it from the Court house.

It was his evidence that he ticked the Warrant of Arrest to identify

the reason

for the arrest which was lacking on the copy given to him. His

further evidence

was that he withdrew the warrant after the file was removed from him

by the

police hierarchy.

The evidence by Serah Amet the Clerk of the District Court who

prepared the

Warrant of Arrest was that the copy she kept at the District Court

was the only

correct copy and without a tick. When questioned on the signatures

being

slightly different her evidence was that two copies of the warrant

were

produced, and the Magistrate signed the two copies separately. There

was no

photocopy of a signed Warrant of Arrest.

Our finding from that evidence is that if there was in fact a

defective or fake

warrant, then the copy held by SC Tali which the leader was privy to

be the fake

one. SC Tali had tampered with it.

Our conclusion therefrom is that the leader had a vested interest in

the

complaint against Peter O’Neill. He was the complainant. The

complaint was

over official corruption and other irregularities in sourcing and

expenditure of

public funding from the Gaming Control Board for Yagaum Hospital in

Madang.

16He became a victim of those irregularities and could not get elected

sooner.

After his return as duly elected Member of Parliament for Madang

Open, he felt

duty bound to right the wrongdoers. No one else could do it for his,

people who -

Page 19 of 61

-

missed out on proper service delivery. He laid a formal complaint

with police.

The police reacted to his complaint and obtained a Warrant of Arrest

against

O’Neill who had directed the procurement of funds from the Gaming

Control

Board for Yagaum Hospital. There was nothing improper on the part of

the

leader in the laying of the complaint.

What turned out to be improper was what happened after the execution

of the

Warrant of Arrest was frustrated, and O’Neill not arrested. The

leader was not

pleased by what transpired. Without restraint and caution expected

of a leader

he let loose his self-control in a subtle way to portray his

dissatisfaction by

publishing articles the subject of these allegations. In the process

the leader

further posted the letter of complaint the Chief Justice sent to the

Police

Commissioner.

The document that later became controversial was brought to the

attention of

the Chief Justice by his associate Togi Maniawa. It was a letter

requesting a

hearing of an application by O’Neill’s lawyer for a temporary stay

of the Warrant

of Arrest to the date set by Justice Miviri. On that letter the Hon

Chief Justice

wrote “Miviri J. Please attend to this matter for a temporary stay

until

21/10/19”.From a reading of the notation by the Chief Justice it was in our

view not a

direction to the trial Judge as asserted in the article by the

leader. It was a

misstatement by the leader of the facts to say that the grant of

stay by Justice

Miviri was consistent with directions by the Chief Justice. The

Chief Justice did

not issue directions or use the word direct to Justice Miviri. The

use of the word

“direct” would connote a compulsion to act. On the converse the

enabling words

“please attend to this matter” exemplifies a request more than a

direction. It

can also be interpreted as requesting Justice Miviri to reconsider

his earlier

position. It was open to Justice Miviri to reconsider or stick to

his earlier stance.

He chose to reconsider and hear the application. We cannot deem the

notation -

Page 20 of 61

-

by the Chief justice as a direction as suggested by the leader.

17

There was nothing unusual, sinister, or intrusive in the way the

Chief Justice

made the request to Justice Miviri to attend to the matter for a

temporary stay.

The date suggested by the Chief Justice was consistent with the date

set by

Justice Miviri.The Chief Justice was entitled to do what he did as head of the

Judiciary when

the decision of Justice Miviri was a decision from chambers and not

a Court

Order. That proposition was affirmed in evidence by the Chief

Justice himself

and the former Chief Justice Sir Arnold Amet that chamber directions

are issued.

The difference between a decision from chambers and a Court Order

was also

distinguished in evidence by the Hon Chief Justice and Sir Arnold

Amet that a

Court Order is subject to an appeal to the higher Court while a

direction from

chambers is more an administrative convenience. We add here that

even though

a direction from chambers of a Judge would not be subject to an

appeal, any

person who was so aggrieved by any such direction, could seek

Judicial Review

of that direction as an administrative decision. It is still open to

challenge.The evidence of the Chief Justice was that he could not direct a

judge to make

orders. It was up to the Trial Judge to independently determine

whether to grant

or refuse the application as it is done in the usual course of

judicial

determinations. Justice Miviri deposed to doing just that. He told

the tribunal

that he made his own independent decision.We also find no evidence that O’Neill appointed the Chief Justice.

The Chief

Justice gave evidence that he was appointed by the National

Executive Council

on 13 November 2018 from a shortlist of 5 names of other senior

Judges. The

appointment process was further affirmed by the former Chief Justice

Sir Arnold -

Page 21 of 61

-

Amet that by law it is the National Executive Council that appoints

the Chief

Justice. That evidence has not been discredited.There may be a hint of a conflict of interest by the Chief justice

under two

circumstances. The obvious one was that at the time the Chief

Justice was

appointed, Hon Peter O’Neill was the Prime Minister and by the

office held, he

was the Chairman of the National Executive Council which was the

appointing

authority.

18There is also the evidence that Peter O’Neill directed Tom Kulunga,

then

Commissioner of Police to approach Sir Gibbs Salika personally on an

Arrest of

former Chief Justice Sir Salamo injia.However, the publication by the leader in the Facebook article that

the Chief

Justice was recently appointed by O’Neill is an inaccurate

statement, distorted

and far from the truth. It is highly irregular and improper for the

leader to

assume that a reader would interpret the words the way he meant it

to be

interpreted. He was intelligent enough to distinguish facts from

untruths.The Chief Justice is the head of the third arm of government and the

appointment to such important position cannot be done by a single

person, even

the Prime minister. By operation of s 169 (2) of the Constitution,

the National

Executive Council is entrusted with the authority to appoint the

Chief Justice by

advice to the Head of State. There is no other way. It seems the

leader was

unaware of this process by his publication. If he was aware, then he

chose to

interpret it his way. The publication of distorted and untruths

renders any hint

of a conflict of interest by the Chief Justice nugatory.Given those facts it is in our view farfetched and beyond the bounds

of

possibility to insinuate a conflict of interest or corruption in the

judiciary in

circumstances where the Chief Justice requested Justice Miviri to

“Please attend -

Page 22 of 61

-

to this matter” as a return favour to O’Neill for appointing the

Chief Justice.On the allegation of deceiving and misleading the Court by O’Neill

and his

lawyers, two copies of the warrants were published, and the leader

compared

them on the Facebook.We are of the view that even though the words under this category of

allegation

were directed at O’Neill and his lawyers, by publishing that a fake

Warrant of

Arrest was used to deceive and mislead the Court to obtain a Court

Order, were

factually wrong and far from the truth.19

The copies posted on the leaders Facebook account were both correct

copies.

None was fake. The Warrant of Arrest that could be described as fake

was the

copy tampered with a tick, by the Police Informant Senior Constable

Kila Tali.Secondly, there was no determination by the Court on the Warrant of

Arrest.

Whether the Warrant of Arrest was fake or had substance was not

determined.

Only a restraining order was given. To allege that the Court Order

for a stay was

obtained by using a fake document was also factually incorrect. The

evidence is

that the warrant that the police wanted to execute was the tampered

one. The

correct copy was in the Court file which O’Neill’s lawyer relied on.

The

application to set aside the Warrant was proper because the two

copies did not

match, one with a tick and the other without a tick.The substantive application by O’Neill for judicial review was never

dealt with

by the Court. The judiciary was distanced from the allegation of the

fake warrant

when the Warrant of Arrest was withdrawn by SC Kila Tali being the

Police

Informant.We find that the articles published in the Facebook pages were not

-

Page 23 of 61

-

calculated

to interfere with the due course of justice or lawful process of the

Court. The

published articles related to a matter that was completed, dead and

done. The

articles did not relate to a matter that was ongoing from which

interference

could be inferred or bring the Court or Judge into disrepute by such

publication.On the allegation of publishing on Facebook, the letter of complaint

by the Chief

Justice, like the Leader, the Chief Justice was entitled to write to

the Police

Commissioner because it would have been inappropriate and demeaning

of his

office to go stand behind the counter at a police station to lay his

complaint. Be

that as it may, the leader was also entitled to react the way he did

as the most

affected person by the letter of complaint.

Our conclusions from the series of articles and the publication of

the letter by

the Chief Justice by the leader is that they constituted

unsubstantiated facts and

unverified conclusions. The leader published them to enhance his

personal

interest more than for the public good as the leader asserts.20

The publications were also intended for the victims of his

unrestrained

utterances to suffer any consequence that followed.

By those findings the issue now is whether the leader has committed

a breach

of a duty alleged under s 27 (5) (b) of the Constitution. This

provision is wide in

scope and encompasses all the subsections before it. It covers

directions under

subsection (4) and obligations under subsections (1), (2) & (3).We deal with the issue this way. Where the specific breach alleged

is not proved

but the evidence discloses a breach of another duty imposed by s 27

of the

Constitution the tribunal will be at liberty to exercise its

discretion to hold that

a duty not specifically charged was breached. The reason for that

is simple. The

provision alleged to have been breached under s 27 (5) (b) subsumes

all

preceding subsections. It was intended to cover a broad range of -

Page 24 of 61

-

misconduct

collectively and not individually.To consider whether a breach under s 27 has been committed we shall

determine the respective subsections through an elimination process.Subsection 4 relates to directions from the Ombudsman Commission and

does

not apply to these allegations. Subsections 2 relates to use of

office for personal

gain and does not apply to these allegations. Subsection 3 relates

to conduct of

spouses, children and associates and does not apply to these

allegations.

Subsection 5 (a) relates to convictions and does not apply to these

allegations.After the eliminations the only provision remaining is subsection

(1).

This provision is subsumed under s 27 (5) (b) which the referrer

alleges was

breached by the leader. If an allegation cannot be charged under

subsection (1)

alone, it can be charged under s 27 (5) (b). They operate

interchangeably.Under s 27 (1) (a) the requirement is that a leader must not place

himself in a

conflict-of-interest situation. The utterances in the Facebook

account do not

constitute a conflict-of-interest by the leader and does not apply

to the

circumstances relating to scandalising the judiciary.21

Under s 27 (1) (b) a leader must conduct himself so as not to demean

his office.

Even though the materials on the Face book platform do not

constitute an

official press release or a function related to his official duties

as Minister for

Police complaining about Court processes in the media was going too

far. The

standing practice was that the police and the Judiciary work at

arm’s length and

not attack each other at will. He as Minister for Police had to lead

in that respect

and protect that relationship. The leader is deemed to have demeaned

his office

by publishing articles of person interest in conflict with his

position as Minister -

Page 25 of 61

-

for Police.

Under s 27 (1) (c) (d) the requirements are that a leader must not

allow his

official or personal integrity to be called into question. We adopt

what we have

just said above. The articles in the Facebook although personal,

were published

when he was a leader, being the Minister for Police and Member of

Parliament

representing the people of Madang Electorate. His personal interests

from a by-

product of a vendetta against O’Neill for supporting his political

nemesis Nixon

Duban to win the election clouded decorum and sound judgement. After

winning the 2017 National Election the leader went in pursuit of

killing the goose

that lay the golden egg so to speak.Even though the articles may not have been intended to scandalise

the judiciary

we cannot find the leaders comments as factual and fair in

circumstances where

the purported facts were in fact misstatements and inaccurate.He failed to exercise restraint as a leader. He failed to warn

himself of the

adverse consequences of breeding negative perception on the

judiciary by an

exploitable and deceivable public. There were proper processes in

place that the

leader could have utilised instead of going too low to let a

gullible public pass

judgement.Even though the bulk of the population in this country have no

access to

Facebook the numerous responses to the leader’s articles and the

publication

of the letter by the Chief Justice from those persons who were

connected to

Facebook attest to the reactions and perceptions from the public.22

The responses tendered into evidence were varied. We reproduce some

of them

verbatim.

Some of the responses insinuated corruption at the highest level

where

wrongdoing was least expected e.g. (It shows all Court system is

corrupt around

PNG); (Its embarrassing for a man known as chief justice to be -

Page 26 of 61

-

involved in

corruption). (Appoint some mature and man of vision to head the

judiciary harm

in the country.Other comments were susceptible to the veracity of the alleged

wrongdoing by

the Chief Justice. e.g. (Hope there is evidence on your post

inciting trouble or

causing ill feeling to people. Otherwise, the 0 should be thankful

that you have

help expose a weakness in the judicial process and he should focus

on improving

and making sure that does not happen again); (Look at all the

mistakes on the

complaint against Police Minister Bryan Kramer… Do we still think

this letter

originally came from the Chief Justice of Papua New Guinea?); (This

is fake letter

by someone who have been bribed by someone who is heavily involved

in those

corrupt deals”.There were also comments which portrayed the leader as a demigod

against

corruption. e.g (BK stood the test of times against Goliath (in

power) and still

persevere. Nothing is new. Only a new Goliath).

Thumbs up Bryan Kramer for your strong standing in fighting

corruption in PNG.

You are the true patriotic leader of PNG to ‘Take back PNG” from

such colluded

corrupt officials.

My champion my hero God be with you).Other commentators splashed accusations on the Chief justice. E.G (0

should

really stay out of issues like this n let judges do their work bkos

he will only loose

his integrity); 0 and PO can manipulate the system with money bags

as usual);

The pay you receive does not satisfy you and your family); “if the

Chief Justice’s

daughter was working with Greg Shepard’s law firm and if so should

CJ be

involved in cases where the law firm is engaged. Conflict of

interest?” Cl tryina

save his own arse for lack of a better word); (In the history of

Papua new Guinea

this 0 is impatient and it seems like he directly involved with Onil

that why he

trinna coverup on this matter).

23 -

Page 27 of 61

-

The responses to the leader’s articles in total when viewed

objectively are at

best disgraceful, shocking, insensitive and even ridiculous.These types of utterances could not have been ignited had the leader

as author

of the articles exercised restraint and refrained from publishing

them. Instead,

the leader let loose his self- control in a subtle way and allowed

his personal

interest to take precedence. Apart from personal satisfaction, what

good

outcome was there to be gained by anyone else from the publication

of

unreserved and factually untrue utterances remains a mystery.The result of his conduct was that public confidence in the

judiciary overall was

denigrated. It gave birth to negative perception and disrespect for

the judiciary

leading to scandalising the judiciary, a government institution

bestowed with a

high degree of trust.By his conduct in publishing factually untrue statements it allowed

his public and

personal integrity into question as to whether he was a leader of

truth thereby

demeaning his office as Minister for Police and position as a

leader.We find that the leader is caught by s 27 (1) (c) of the Organic Law

on Duties and

Responsibilities of Leadership. Even though the leader was not

charged directly

under subsection (1) (c), subsection (5) (b) under which the leader

was charged

is wide, and it covers all the responsibilities imposed on a leader

which includes

subsection (1) (c).The remaining provision is section 27 (1) (d). The requirement under

this section

is that a leader must conduct himself so as not to endanger or

diminish respect

for and confidence in the integrity of government in Papua New

Guinea.

“Government” is wide in scope and covers all government entities and

instrumentalities which includes the judiciary. Even though the

articles were not

recognised official media releases, they related to official

government functions

the judiciary was involved in. We adopt what we said under -

Page 28 of 61

-

subsection 1 (c) in

this regard.24

Insinuation of a conflict of interest by the ChiefJustice in the

performance of his

official functions is not supported by evidence. There is no

evidence that O’Neill

or his lawyer solicited assistance from the Chief justice apart

from writing a

letter requesting a hearing. O’Neill’s lawyer served the interest

of his client as is

the normal duty of lawyers in this country and other countries that

ascribe to

the rule of law.From the evidence before us two extremes of leadership are

displayed. O’Neill

being a leader challenged the Warrant of Arrest as defective

through the normal

judicial process which is available to one and all. It is ironic

that the Leader also

challenged, a Warrant of Arrest as fake on Facebook which is also

available to

the public.There was nothing untoward in the approach taken by O’Neill’s lawyer

to pursue

his client’s interest in Court. On the converse, the articles on

Facebook

denigrated the high respect and confidence the public has of the

Judiciary. It

created doubts as to whether the last bastion of hope is wrought

with corruption

which the judiciary is supposed to protect and defend.The varying responses to the articles on Facebook attest to this.

The Facebook

articles also created doubts in the minds of the learned members of

the

community on the independence of the judiciary a government body

when the

Chief Justice is alleged to have instructed another judge to issue

orders. The

foundation of the judiciary is the independence of the judge in

decision making.By insinuating that the Chief Justice directed another judge (which

was factually

untrue) to make a certain decision impinges substantially on the

independence -

Page 29 of 61

-

of the judiciary thereby demeaning the integrity of the Chief

Justice, lowering

his authority, endanger public confidence in the administration of

justice and

scandalising the judiciary overall amounting to misconduct in office

under s 27

(5) (b) of the Constitution.The allegations relating to scandalising the judiciary through

articles on the

leaders Facebook account have been proved to the required standard.25

We find the leader guilty of misconduct in office pursuant to s 27

(5) (b) of the

Constitution for allegations 1 and 2.On the allegation under category 4 relating to the letter of

criminal complaint

by the Chief Justice, there was an element of undermining public

confidence in

the administration of justice in the context that, the Chief justice

who was least

expected to be in trouble with the law had joined the que and become

another

complainant.Despite that we do not find any dishonesty or conflict of interest

on the part of

the leader in obtaining and publishing the letter on Facebook. The

leader was

the person most affected by the letter, and he was entitled to

react. Secondly,

the letter by the Chief Justice if properly attended to by police as

requested, it

would have been in the public domain anyway.

We find the leader not guilty under category 4 of the allegations.Allegation 3. Involvement and interference in police operational

matters

resulting in the termination of Mr Paul Nii Director Legal Services.Under this category the referrer alleged that the leader interfered

in police

operational matters as then Minister for Police in the termination

of one Paul

Nil who was then the Director of Police Legal Services; that the

removal was

made after Mr Nii provided legal advice against the arrest of Peter

O’Neill which

did not go down well with the leader’s interests because the arrest

of Peter -

Page 30 of 61

-

O’Neil arose out of a complaint by the leader.

The leader denied any involvement or interference in the termination

of Mr. Nii.

His contention was that the termination was for abuse of a hire car

and he was

not guilty of misconduct in office under s 27 (5) (b) of the

Constitution.The Law under s 197(2) of the Constitution is that a member of the

police force

is not subject to direction or control by anyone outside the police

force. This

includes the Minister responsible for Police.26

The evidence under this allegation came from the victim of the

termination, now

Magistrate Paul Nii who was at the relevant time Director Legal

services in the

Royal Papua New Guinea Constabulary. His evidence briefly was of

being in the

Police Commissioner’s office when the leader had a discussion with

the then

Acting Commissioner of Police over a complaint by the leader against

Peter

O’Neill. From that discussion he was directed to do a file search on

an application

by O’Neill to set aside a Warrant of Arrest.While returning from the search the Acting Commissioner of Police

directed him

to go to Boroko Police Station to give advice on a Court Order

O’Neill had

obtained to set aside a Warrant of Arrest because the Police at

Boroko were

divided on the Court Order. He gave advice against the arrest of

O’Neill despite

the Police Commissioner’s insistence to give legal clearance for

police to arrest

O’Neill. A second opinion on the Court Order gave the same advice

and O’Neill

was released.On 27 December 2019 he was suspended by a show cause notice for

abuse of

office and breach of contract relating to the use of two motor

vehicles at Police

Department expense and eventually terminated.Mr Nii in evidence denied the suspension as related to the hire car.

-

Page 31 of 61

-

His assertion

was that he was allowed to use the vehicle by the Managing Director

Nelson

Tengi while his suspension was upon pressure by the leader for

giving legal

advice against the arrest of O’Neill. He relied on a letter by Mr

Nelson Yarka the

accountant for Lama Rent A Car as supporting his assertion on the

hire car.According to the letter from Mr. Daniel Yarka the, the vehicle in

question was

hired on a retainer basis by the Police Department commencing 22

April 2018

for 38 months to be invoiced on 6 monthly bases. When Mr Nii went to

return

the vehicle in April 2019, he was allowed to keep the vehicle by the

Managing

Director for reasons he did not know.The letter was confusing as it portrayed a scenario where Mr. Nii

had legitimate

use of the vehicle as allowed by the Managing Director and Police

Department

could still pay the rates for hire.

27A simple calculation on the retainer shows that 18 months retainer

period would

have lapsed on 22 June 2021. Mr Nii had custody of the hired vehicle

in 2019

while it was still under the retainer by the Police Department. Our

conclusion is

that the suspension was for the unauthorised use of the hired

vehicle and none

other.We now revert to the substantive allegation that the leader

interfered in police

operational matters to have Mr Nii terminated.The oral evidence of Mr Nil was that the Commissioner of Police

seemed to be

under pressure when he directed him so many times to give clearance

for the

arrest of O’Neill. He was of the firm view that the leader pressured

the

Commissioner to give legal clearance for the arrest of O’Neill after

their earlier

meeting in the Police Commissioner’s office.

When asked by counsel to verify “so many times” he was unable to

give a

specific number. We consider this piece of evidence by Mr Nii as -

Page 32 of 61

-

grossly

exaggerated and unsubstantiated.The other evidence on this allegation was from the Facebook

articles, where the

leader referred to interference by a certain police officer who

vigorously

opposed the arrest of O’Neill insisting that the Court Order forbade

police from

arresting him. The alleged police officer was not named in the

Facebook articles.We find as a fact that political interference in operational matters

of the Police

Force had occurred. Two instances signify our findings.In the first instance there is evidence that former Commissioner of

Police Tom

Kulunga and the then Commander Special Operations, David Manning

went to

the private residence of the former Deputy Chief Justice Sir Gibbs

Salika and had

discussions on a purported Arrest of the former Chief Justice Sir

Salamo I njia at

the behest of the former Prime Minister Peter O’Neill.In the second instance the evidence before us is that the leader, as

then Minister

for Police held discussions with the Commissioner of Police on the

Arrest of

former Prime Minister O’Neill from his personal complaint.

28These are testaments of direct political interference in police

operational

matters by leaders. Arrest of persons is an operational matter for

the police to

the exclusion of all of us. It is a breach of and a blatant

disregard of the

constitutional directive under s 197 (2) which restrains all and

sundry from

interfering with operational matters of the Police Force.Even though there was an element of interference and a conflict of

interest by

the leader in police operational matters concerning his personal

complaint, we

cannot safely connect those observations to interference by the

leader in the

suspension and termination of Mr. Nii. We find the leader not guilty

of this

allegation. -

Page 33 of 61

-

The balance of the allegations relates to the District Development

Authority

(Authority) and its enabling Act. We propose to make general

observations on

relevant provisions of the Act before proceeding with the

allegations.We start with the standing notion that laws are there to be obeyed

by one and

all. Where there is a breach or a disobedience to any law, sanctions

naturally

follow. District Development Authority (amendment) Act of 2014 (the

Act) is one

such law and enjoys no exception.The Authority is by statute pursuant to s 4 (1) (a) of the Act a

corporate body. It

does not require certification by the Investment Promotion Authority

to be

recognised as a company. It replaced the functions of the former

Joint District

Planning & Budget Priorities Committee (JDPBPC) pursuant to s 33A of

the

Organic Law on Provincial and Local Level Government Act and comes

under the

umbrella of the Department of Provincial and Local Level

Governments.It has a board constituted by the Open Member as charman and all the

presidents of the Local Level Governments in the District. The

Chairman

appoints three persons representing the community.By operation of s22 the District Administrator (DA) who is a public

servant and

subject to the Department of Personnel Management, becomes the Chief

Executive Officer (CEO) of the Authority.

29He/she is the only person possessed of an overlapping responsibility

as DA of

the District and the CEO of the Authority. The incumbent DA requires

no specific

appointment as CEO because he is already recognised by s 22 as the

CEO to the

Authority.Our reading of the Act is that the setting up of the Authority was a

change in the

regime of centralized funding control to be closer to the district.

It was intended

to facilitate an effective and coordinated approach to development

and service -

Page 34 of 61

-

delivery in each District and nothing else.

Specific functions provided under s 5 (b) were to develop, build,

repair, improve

and maintain roads and other infrastructure only. The Authority also

possessed

an underlying power to do all that are necessary or convenient to be

done in the

implementation of the functions. Other functions specified under s 5

only

compliment the development and service delivery requirements.All functions of service delivery are as prescribed by the Act or by

regulation

accompanying the Act or by determinations from the portfolio

minister

pursuant to s 6, or directions by the Minister pursuant to s 20 of

the Act. These

requirements are mandatory. At the time of the allegations there was

no

regulation or any Ministerial determination or direction in force.

The Act stood

alone.One of the functions of service delivery is to approve disbursement

of

appropriated funding under the District Support Grants (DSG) and

District

Services Improvement Programme (DSIP) funds. Apart from these

appropriated

funds, the Authority can receive funding from other sources like

grants and

donations if any. All these funds are paid into the district

treasury and

expenditures recorded accordingly in the Provincial Government

Accounting

System (PGAS) as they are all deemed public funds.All financial matters for the Authority are subject to part VIII of

the Public

Finance Management Act 1995 and according to financial instructions

and

guidelines issued from time to time.30

The established practice in financial matters is that the District

Finance Office or

District Treasury these days raises the requisition and General

Expenses for

invoices submitted to it after the initial approval is given by the

board through

the Chairman. The DA as section 32 officer authorises payment and -

Page 35 of 61

-

expenditures are recorded accordingly in the PGAS.

In the present case soon after the Leader was elected as MP for

Madang in the

2017 National Elections, to improve service delivery for the

district, he

orchestrated the creation of Madang Ward Project office and

established a new

structure to administer and implement projects and other services

from an

office rented at Divine Word University. A secretariat was

established, and staff

were employed to implement the functions of the Ward Project

Office.The leader further orchestrated the incorporation of Madang Ward

Project

Limited as a business arm to implement ward projects and other

projects

initiated by the Ward Project office and approved by the board. The

effect of

this setup was that some of the functions of the DA and staff in the

existing

structure were subsumed into the new structure.In like manner the leader also caused to be incorporated another

company

named as Madang Works & Equipment Ltd to implement road projects

which

were completely in dilapidated states. Large sums of DSIP funds were

transferred to this company following a Court Order. The two

companies were

owned by the Madang DDA as shareholder with the same single

director.Therefrom, the leader among others proposed, office rental and

engagement of

consultants which the board eventually endorsed. It is from this new

structure

and engagement of consultants and related issues that led to the

investigation

by the Ombudsman Commission leading to the categories of allegations

against

the leader the subject of this proceeding.We now deal with Allegations 5 & 6 together as they relate to the

engagement

of Tolo Enterprises.31

Allegation 5: Allowing an associate company, namely Tolo Enterprises

-

Page 36 of 61

-

Ltd to

benefit through consultancy services to the Madang District

Development

Authority

Allegation 6: Misappropriation of K455,751.20 to the use of Tolo

Enterprises Ltd

a company owned by an associate.

The allegations under these categories are that between 1st December

2017 and

31st June 2020 the Leader failed to carry out the obligations

imposed by Section

27(1)(b)(c) of the Constitution when he allowed an associate

company, namely

Tolo Enterprises Ltd, to financially benefit through consultancy

services to the

Madang District Development Authority thereby being guilty of

misconduct in

office under Section 27(5)(b) of the Constitution.

It is further alleged that the leader dishonestly applied the sum of

K455, 751.20

to the use of Tolo Enterprises Ltd who was an associate company

thereby being

guilty of misconduct in office under Section 13 (a) of the Organic

Law on the

Duties and Responsibilities of Leadership.

The position of the referrer is that Tolo Enterprises was not

properly engaged

from the beginning and as such the benefits that were received by

the company

were void.

The leader contended that that the charge was defective for failing

to plead

sufficient and relevant material facts. It was also the contention

that Tolo

Enterprise was not an associate company or owned by an associate or

was he a

shareholder or director to fall under the definition of associate

under s 1 of the

Organic Law. It was the assertion that Tolo’s engagement for

consultancy

services was approved by the board along with 04 others by

resolution 1/2018

of 11 January 2018 and that the Engagement of consultants is

permitted under

s 7 of the DDA Act. The amount paid to the company were for services

rendered

under the agreement and adequately acquitted and therefore there was

no

misappropriation.

He then submitted that knowing a person or being acquainted with

them is not

evidence that they are associates within the definition under

Section 1 of the

Organic Law. -

Page 37 of 61

-

32

Because the referrer failed to plead properly the allegation of

misappropriation

and the element of associate, the allegations should be dismissed.

The facts under these allegations are that the leader after a prior

meeting with

Mrs Hitolo Carmichael Amet proposed to the Board the engagement of

Tolo

Enterprise as technical adviser/consultant. In the minutes of board

meeting No

1/2018, the leader was the sponsor of the agenda for the engagement

of the

company and 4 others for consultancy services to the Authority.

After

introducing the agenda, the leader recused from the meeting since he

personally knew Mrs. Hitolo Carmichael Amet. By doing so he complied

with the

requirements under s 15 of the Organic Law to disclose his interest

to avoid a

conflict-of-interest situation.The board approved the engagements for an initial 6 months and paid

them

from DSIP funds. Thereafter Toles consultancy engagement was

extended, and

eventually paid from DSIP funds for services rendered totalling more

than

K400,000. There is no evidence of what happened to the other

consultants after

their terms expired.

To find the leader guilty of misconduct in office under these two

categories there

must be proof of the allegation that Tolo Enterprise Ltd was an

associate

company in the terms of the definition of “associate” under s 1 of

the Organic

Law.The definition under the Organic Law defines “associate” in the

following terms;

“In relation to a person to whom this Law applies, includes a member

of his

family or a relative, or a person (including an unincorporated

profit-seeking

organization) associated with him or with a member of his family or

a relative.”By virtue of the definition under the Organic Law we deem the leader

as an